Week of January 27, 2025 | Iran Unfiltered is a digest tracking Iranian politics & society by the National Iranian American Council

•

• Navigating Diplomatic Shifts: Iran’s Evolving Stance on Direct Talks with the U.S.

Navigating Diplomatic Shifts: Iran’s Evolving Stance on Direct Talks with the U.S.

With Donald Trump’s return to the White House for a second term, the question of direct talks between Iran and the United States has resurfaced in Tehran. Senior Iranian officials, once dismissive of open dialogue with Washington, are now hinting at new possibilities—even as some conservative factions harshly criticize such engagement.

Just a few years ago, even mentioning direct Iran-U.S. talks was considered a political taboo. Now, Iranian authorities from various branches of government have publicly acknowledged the possibility of negotiation. Several officials, including Hamidreza Haji Babayi—Deputy Speaker (Nayeb-e Raees) of the Iranian Parliament who is close to conservative circles—have stated that Iran is not inherently hostile to the United States and is open to “fair” or “just” talks. Mohammad Javad Larijani, an advisor to the Supreme Leader, stated in a television interview that “we will soon deal with America… If the compromise of the system requires it, we will also deal with the devil in the depths of hell.” He called Trump a “first-class criminal” while advising that if negotiations with the U.S. take place, Iran should maintain caution for a considerable period and postpone the negotiations for a while.

At the same time, Majid Takht-Ravanchi, Deputy Foreign Minister for Political Affairs, affirmed that Iran has been preparing strategies for how to engage with the second Trump administration but stressed that no formal messages had been exchanged and that Iran would not finalize any negotiation stance until Washington’s policies become clearer.

Observers note that practical concerns—such as curbing sanctions, stabilizing the currency, and addressing the mounting costs of Iran’s nuclear advances—appear to be prompting once-skeptical officials to reconsider dialogue. Amid this changing climate, Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei appeared to offer contingent support for the Iranian government to negotiate with the United States. He tweeted this week, stating “Behind the smiles of diplomacy, there are always hidden and inner enmities and grudges of the evil one. Let us open our eyes and be careful with whom we are facing, dealing with, and talking. When a person knows his opponent, he may make a deal, but he knows what to do. We must recognize and know.”

Despite these signals from some Iranian officials, conservative and hardline factions have mounted a vigorous counter-campaign. A video surfaced of protesters in Tehran dressed in burial shrouds, shouting “Death to infiltrators” and demanding an end to any talk of negotiating with Washington. These demonstrations also targeted Mohammad Javad Zarif, now Deputy for Strategic Affairs under President Massoud Pezeshkian, accusing him of undermining national interests by advocating dialogue. Some conservative Members of Parliament (MPs) want Zarif removed from his position, alleging he and his family might hold dual nationality and claiming that laws prohibit those with foreign citizenship from holding sensitive positions in government. Under President Pezeshkian, a parliamentary commission on national security called for the removal of high-ranking officials who appear open to direct talks with the Trump administration, warning that unity under the Supreme Leader’s guidance is crucial given renewed U.S. rhetoric.

Iranian deputy presidents and foreign policymakers, including Zarif, were sharply criticized following interviews at the World Economic Forum in Davos, where topics such as mandatory hijab and the possibility of direct talks with the U.S. were openly discussed. Hardline publications like Kayhan labeled Zarif’s remarks in Davos as humiliating and against Islamic and revolutionary principles. Conservative MPs, such as Kamran Ghazanfari, have led protests accusing government officials of betraying national interests.

However, in an interesting statement, Deputy Speaker of Parliament Hamidreza Haji Babayi declared that Iran is not at war with the United States and is prepared to negotiate as long as talks remain equitable, illustrating a potential shift from the uncompromising stance more often linked to the Supreme Leader’s directives. Nevertheless, tensions between advocates of dialogue and staunch opposition persist.

Another viewpoint of disagreement comes from Sadeollah Zarei, a commentator close to Iran’s security institutions and a columnist for Kayhan. He believes that Iran’s circumstances are not so dire as to justify making compromises against the country’s national interests. According to Zarei, the international and regional landscapes have changed significantly compared to a decade ago—citing factors such as the war in Ukraine, a divided UN Security Council, and shifts in economic and diplomatic ties that have increasingly aligned with Eastern powers rather than the West. He argues that entering negotiations with the United States risks alienating potential partners in blocs like the Shanghai Cooperation Organization or BRICS, who might doubt Tehran’s commitment to deeper ties outside the Western sphere. Zarei contends that previous attempts at rapprochement with Washington have yielded no meaningful reduction in U.S. hostility and questions whether those urging a “comprehensive agreement” with the U.S. truly believe Iran deserves regional or international prominence. He concludes that negotiating with Washington is a double loss for Iran—benefiting only America while undermining Tehran’s opportunities for broader, more balanced engagements.

Iran’s political landscape thus sits at a crossroads, torn between those seeking to mitigate sanctions through diplomatic engagement and those who firmly believe Washington’s intentions remain implacably hostile. Khamenei’s warnings and the complexities of parliamentary debate all underscore broad wariness about dealing with another Trump administration. If there is any path toward agreement, it will require bridging these internal divides, clarifying U.S. objectives, and establishing terms that differ from the original JCPOA. As Iranian officials await clearer signals from Washington, debate continues on the streets, in parliament, and behind closed doors in high-level diplomatic discussions. Whether direct talks take place or the stalemate endures, the outcome will undeniably shape Iran’s immediate future and broader role on the international stage.

Abbas Araghchi, the Iranian Foreign Minister, arrived in Kabul, the capital of Afghanistan, on Sunday, January 26. He is the highest-ranking Iranian official to visit the country since the Taliban regained power. Sources indicate that discussions on “Afghan refugees” and “Iran’s water rights from the Helmand River” are among the main topics on the agenda.

According to Ismail Baghai, spokesperson for Iran’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the visit aims to “strengthen bilateral relations, safeguard Iran’s national interests, and engage over mutual concerns and shared priorities.” After arriving in Kabul, Mr. Araghchi met with Amir Khan Muttaqi, acting Foreign Minister of the Taliban government. During this meeting, the two sides discussed political, economic, and security relations between Iran and Afghanistan. Amir Khan Muttaqi expressed hope that the visit would “elevate relations between the two countries.” Mr. Araghchi, for his part, emphasized that trade, economic, and political ties between the two nations are already on solid footing and that this trip could further bolster those relations.

Mohammad Hossein Ranjbaran, adviser to Iran’s Foreign Minister, reported that the issues of “Afghan refugees” and “Iran’s water rights from the Helmand River” were discussed in Mr. Araghchi’s meeting with Mr. Muttaqi. According to Mr. Ranjbaran, both sides agreed on the importance of organizing and facilitating the honorable return of Afghan refugees to Afghanistan. Concerning Iran’s water rights from the Helmand River, Afghan officials stated that they were “mobilizing all technical resources to channel water toward Iran in order to prevent wastage.”

In recent years, the Helmand River water rights have been a contentious issue between Iran and Afghanistan. Under a 1972 agreement, Afghanistan is supposed to release 820 million cubic meters of water annually from the Helmand River into Iran’s Sistan region. Taliban leaders have consistently reiterated their commitment to uphold and implement this agreement.

During this one-day trip, Mr. Araghchi also held talks with Mohammad Hassan Akhund, the Taliban’s Prime Minister, and was scheduled to meet other officials, including the Taliban ministers of agriculture and of industry and mining. His itinerary further included discussions with the acting defense minister, members of the Shia Ulema Council of Afghanistan, and a gathering with a group of Iranian women residing in Afghanistan.

During the meeting with Mohammad Hassan Akhund, Mr. Araghchi referred to the challenges faced by Afghan refugees in Iran and the water issue, stating, “These two subjects should become platforms for expanding cooperation, and Iran is committed to managing the return of undocumented Afghan refugees in a dignified manner.” The Taliban’s Prime Minister urged more Iranian delegations to visit Kabul to strengthen and expand diplomatic, political, and economic ties.

An Iranian business delegation of 15 traders accompanied Mr. Araghchi on this trip, according to the Iranian Foreign Minister’s adviser. Afghanistan has welcomed Iranian investment, and Iran likewise seeks to seize this opportunity, with both nations subject to harsh Western sanctions.

This marks the first official visit by an Iranian Foreign Minister to Afghanistan since the Taliban recaptured power there. Previously, Taliban foreign ministers had traveled to Iran multiple times. The last time an Iranian Foreign Minister visited Kabul was in 2018, when Mohammad Javad Zarif went to Afghanistan under the internationally recognized Afghan government.

Meanwhile, the newspaper Jomhuri-ye Eslami reported that “despite experts’ warnings, Mr. Araghchi proceeded with his trip to Kabul.” The paper noted that while neighboring countries should indeed be a priority for foreign policy and every effort should be made to deepen and enhance those ties, there remains a question as to whether “such a visit, at the level of a foreign minister, is appropriate when Iran itself does not officially recognize the Taliban government or exchange ambassadors.”

The article criticized the idea of a “rebellious, backward group without domestic legitimacy” that fails to “recognize basic women’s rights” and warned that such a trip could distress Tajik, Uzbek, Hazara, and other minority groups with historic ties to Iran. Moreover, the report raised concerns over the International Criminal Court’s warrants for the Taliban leadership on charges of terrorism and human rights violations, questioning whether Iran could take pride in such an engagement.

A campaign advocating for the “Ask of lifting house arrest” initiative was taken down from the Karzar platform just 48 hours after it launched, despite amassing over 17,000 signatures in that short span. Visitors to the campaign’s page encountered a notice stating “This campaign has been suspended due to the order of the Working Group on Determining Criminal Content,” with no additional explanation. This working group, reportedly comprising 12 members, operates under the supervision of the Prosecutor General’s Office.

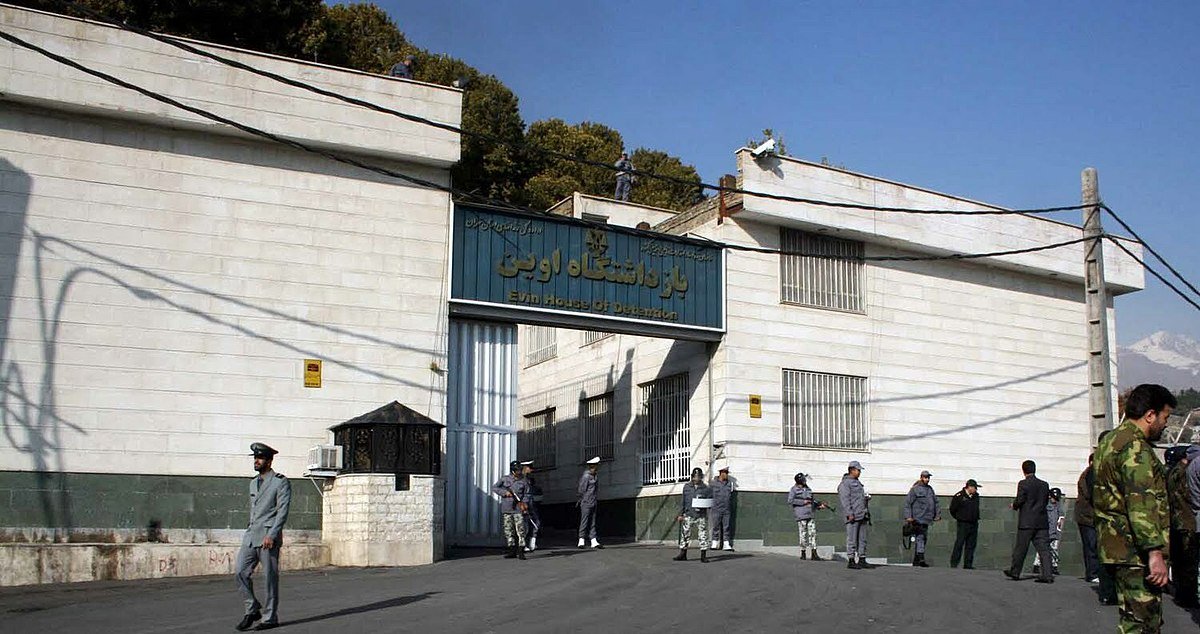

Before its removal, several prominent figures—among them Mostafa Tajzadeh, Abolfazl Ghadiani, and Alireza Beheshti Shirazi (all in Evin Prison), as well as Saeed Madani (in Damavand Prison)—had publicly endorsed the cause. Rahim Ghomeyshi, one of the organizers, thanked Karzar’s administrators for allowing the campaign to operate “at least for a day and a few hours,” noting that it might have reached “hundreds of thousands of signatures” within a week had it continued.

The primary goal of the petition was to free Mir Hossein Mousavi, Mehdi Karroubi, and Zahra Rahnavard from house arrest, using the upcoming 14th anniversary of their house arrest on February 14 as a hook. The Green Movement leaders have been harshly punished for challenging the outcome of the 2009 Presidential elections, which many view as a fraud, and subsequent actions urging demonstrations in Iran in solidarity with the Arab Spring. Calls for their release have resonated with the Iranian public over the years, though the Supreme Leader and Iranian system writ large have not budged.

In response to the campaign’s removal from Karzar, organizers urged supporters to continue signing in the comment section of their Telegram channel. However, halting the effort just 48 hours after its inception prompted criticism from numerous political figures and media outlets.

Ardeshir Amir-Arjmand, an attorney and campaign signatory, emphasized Mehdi Karroubi’s backing of this “End House Arrest” initiative—a call not only for freeing three individuals but also for resisting the systematic violation of citizens’ rights. He observed, “Shutting down this citizen-driven movement in less than 48 hours, after 17,000 signatures were gathered, illustrates the government’s fear of public protest and peaceful demands. It will only strengthen people’s resolve.”

Similarly, Feyzollah Arab-Sorkhi, a political activist, criticized the directive to suspend the campaign in a post on X (formerly Twitter), calling it “a tragicomedy that will be remembered.” Other prominent voices on social media also denounced the shutdown.

Writing separately, Issa Saharkhiz noted that from the first hints of an “End House Arrest Campaign”—initiated by war veterans and families of fallen soldiers—it was clear the government “would not tolerate a mass grassroots effort”. He explained that a possible independent demonstration on February 14 (if Green Movement leaders Mir Hossein Mousavi, Mehdi Karroubi, and Zahra Rahnavard remained under house arrest) seemed unacceptable to authorities. Saharkhiz further mentioned that support had primarily come from private citizens, rather than major reformist or civil-society organizations, implying the government “fears organized public action—even if completely legal and nonviolent.”

As February 14 nears, the Reform Front of Iran issued a statement urging their release and the need for an “immediate end to this unjust practice.” The group deemed the detention of government critics detrimental to national interests, asserting that freeing political and civil prisoners is an essential step toward restoring public confidence.

In its January 28 statement, the Reform Front underscored that “a government cannot ensure its longevity by eliminating opponents and critics,” and characterized the imprisonment of activists, journalists, attorneys, and intellectuals as indicative of systemic injustice and a deviation from democratic principles.

The Reform Front expressed hope that the justice-oriented stance of President Masoud Pezeshkian’s administration might prompt the end of such repressive measures, including the ongoing house arrests of the Green Movement leaders. The Front consists of 27 parties and groups—including the Mosharekat Party, the National Trust Party, and the Executives of Construction Party—and acts as an umbrella for Iran’s reformist movement.

Concerns have grown regarding the rising cost of medications, shortages of essential drugs, and concerns over further price hikes—particularly for treatments for chronic illnesses. These challenges have deepened in the face of systemic challenges, including sanctions and corruption.

Even before the formation of the new cabinet and the parliament’s vote of confidence in ministers, Masoud Pezeshkian issued directives to address the alarming state of the pharmaceutical sector, involving the Planning and Budget Organization and Central Bank. In early 2024, concerns over drug shortages—particularly warfarin, a life-saving anticoagulant—were raised in media reports. Cardiologist Dr. Shabnam Mohammadzadeh and Vahid Mahallati, Vice President of the Drug Distribution Association, warned of fatal risks due to these shortages. They emphasized that importing new drugs does not necessarily resolve shortages but often triggers price surges and new supply gaps.

Months later, the situation has deteriorated further. Prices for some medications have surged up to four times, sparking public anxiety. At the same time, insurance providers admit they cannot cover the rising costs, exacerbating the economic burden on citizens already struggling with a worsening financial crisis.

On January 31, Tasnim News Agency reported that drug price hikes ranged from 15% to over 150%, with some medicines reaching nearly four times their previous cost. Insurance companies stated they lack the funds to cover these increased expenses.

According to Iran’s Health Minister Mohammadreza Zafarghandi, the government approved drug price increases to prevent production halts, as many pharmaceutical companies faced unsustainable manufacturing costs. Mehdi Pirsalehi, head of the Food and Drug Administration, previously acknowledged that 370 types of medications had increased in price, with some injections rising from 6,000 to 19,000 tomans.

Meanwhile, Behnam Sabour, head of Tehran’s Pharmacists Association, expressed hope that if insurance companies expand coverage, patients will not bear the full brunt of these increases. However, serious doubts remain, as Social Security officials claim they have yet to receive any official directives to expand drug subsidies.

Mehdi Nasihi, CEO of Iran’s Health Insurance Organization, warned that the extent of drug price increases is beyond the organization’s financial capacity. He stated that only additional government funding could help mitigate the impact. Without it, patients will be forced to cover the rising costs out of pocket.

Meanwhile, MP Salman Eshaghi revealed that many pharmacies are unable to stock critical medications due to financial instability, with the industry facing nearly 3 trillion tomans in bounced checks. Pharmacists are reluctant to supply drugs that insurance companies may not reimburse them for. Eshaghi further highlighted the poor quality of some domestic drugs, recalling past cases where substandard medications led to deaths among hemophilia and dialysis patients.

Beyond skyrocketing costs, shortages continue to plague Iran’s pharmaceutical sector. Hadi Ahmadi, a senior official in the Pharmacists Association, revealed that the government slashed the 2024 budget for the Daroyar Plan (a subsidy program for medicines) by 50%, leaving a major funding gap that directly affects patients’ out-of-pocket costs. Originally launched under President Ebrahim Raisi, the Daroyar Plan aimed to stabilize drug prices through insurance reimbursements. However, widespread reports suggest it has failed to curb both price surges and supply issues.

Government officials blame Western sanctions and the so-called “drug mafia” for the crisis. Yet, recent reports indicate sudden price increases of 200% to 400% for some medications, while the Health Ministry admits that 300 essential drugs are currently in short supply.

Iran’s pharmaceutical sector is also experiencing a significant production decline. A parliamentary research report noted an 18.5% drop in drug production among publicly listed companies in 2024, while Jafar Ghaempanah, a senior government official, estimated an overall 30% decline in pharmaceutical output.

To make matters worse, Iran is facing a growing exodus of pharmaceutical professionals, further threatening the industry’s stability. The Iranian drug crisis is now a multi-dimensional catastrophe, impacting drug availability, affordability, quality, and long-term industry sustainability. Without immediate and structural interventions, experts warn that both public health and the pharmaceutical sector itself are at serious risk of collapse.

President Masoud Pezeshkian’s governing style has recently become the focus of intense scrutiny and debate within Iran’s political and media circles. Observers from across the spectrum—ranging from reformists to conservative-leaning commentators—have offered diverging opinions, accusing him at times of populism while also examining whether such criticisms hold merit.

The controversy was sparked shortly after Hossein Mar’ashi, Secretary General of the Executives of Construction Party, offered a public assessment of President Pezeshkian’s first five months in office. According to him: “The key issue is that the country cannot be governed with only 10 to 15 percent efficiency, even if it is on the right path. The country needs rapid growth and prompt decision-making. It sometimes takes months to address a single issue, and I’m dissatisfied with such slow progress.”

The discussion intensified when Pezeshkian and his First Executive Vice President participated in building a wall at a school construction site in Khuzestan Province. This act—intended to highlight educational disparities and a shortage of school facilities—immediately drew criticism from political figures, journalists, and social media users, some of whom branded it “populist.” Detractors likened it to tactics employed by former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, known for blending hands-on appearances with anti-expert policy approaches.

However, a range of analysts and publications—including Noor News, reformist thinker Abbas Abdi, and the conservative-leaning Javan newspaper—have pushed back against this accusation. They note that true populists generally champion “the people” over specialists, dismissing expert opinions in favor of raw public sentiment. By contrast, Pezeshkian has consistently highlighted the importance of expert consensus and refrained from sweeping promises during his campaign, demonstrating what many see as the opposite of populist governance. His decision to take part in a symbolic construction project, supporters argue, was aimed at drawing attention to stark inequities in the educational sector rather than pandering to voters.

Abbas Abdi delved into why such gestures might trigger suspicion, pointing out that many Iranians recall the Ahmadinejad era, when bold rhetoric and headline-grabbing stunts often overshadowed substantive policies. While Abdi concedes that publicly addressing educational needs is commendable—especially in under-resourced areas such as Khuzestan and Sistan-Baluchestan—he cautions that it does not automatically translate into meaningful, systemic reforms. Instead, Abdi emphasizes Pezeshkian’s non-populist credentials: the President avoids grandiose pledges, welcomes input from experts (even when it conflicts with public sentiment), and remains open to revising flawed policies. The real question, Abdi suggests, is whether Pezeshkian will implement deeper structural changes in education and economics to tackle the root causes of inequality.

Meanwhile, the Javan newspaper took a different angle by arguing that critics labeling Pezeshkian “populist” might themselves be more populist in approach. Javan’s editorial contends that those who routinely invoke “the people” as a monolithic entity—while rejecting pluralism—demonstrate classic populist tendencies. In contrast, they argue, Pezeshkian is committed to expert-led policymaking and has proposed measures that are sometimes unpopular, such as energy conservation and eliminating artificial currency rates. Javan further theorizes that certain reformist groups could be uneasy about Pezeshkian cultivating a direct connection with ordinary citizens, fearing a diminution of their own influence if the President bypasses traditional elite-driven channels.

In a separate development, political commentator Ahmad Zaidabadi posted on social media suggesting that President Pezeshkian should distance himself from ongoing nuclear negotiations with the Trump administration. According to him: “Perhaps President Pezeshkian should relinquish responsibility for negotiations, officially hand over decision-making on the matter to his political rivals, and avoid getting caught in a process that could amount to domestic political self-sabotage.”

Altogether, these debates paint a picture of a presidency caught between competing expectations. One side demands hands-on demonstrations of empathy and action, while the other insists on strict policy expertise devoid of any hint of populism. Amid these divides, President Pezeshkian’s nascent administration has only begun addressing the myriad challenges facing Iran, including economic strain, educational disparities, and foreign policy complexities. Whether he can balance symbolic gestures with the substantive reforms many Iranians expect remains a crucial question that will define his tenure.