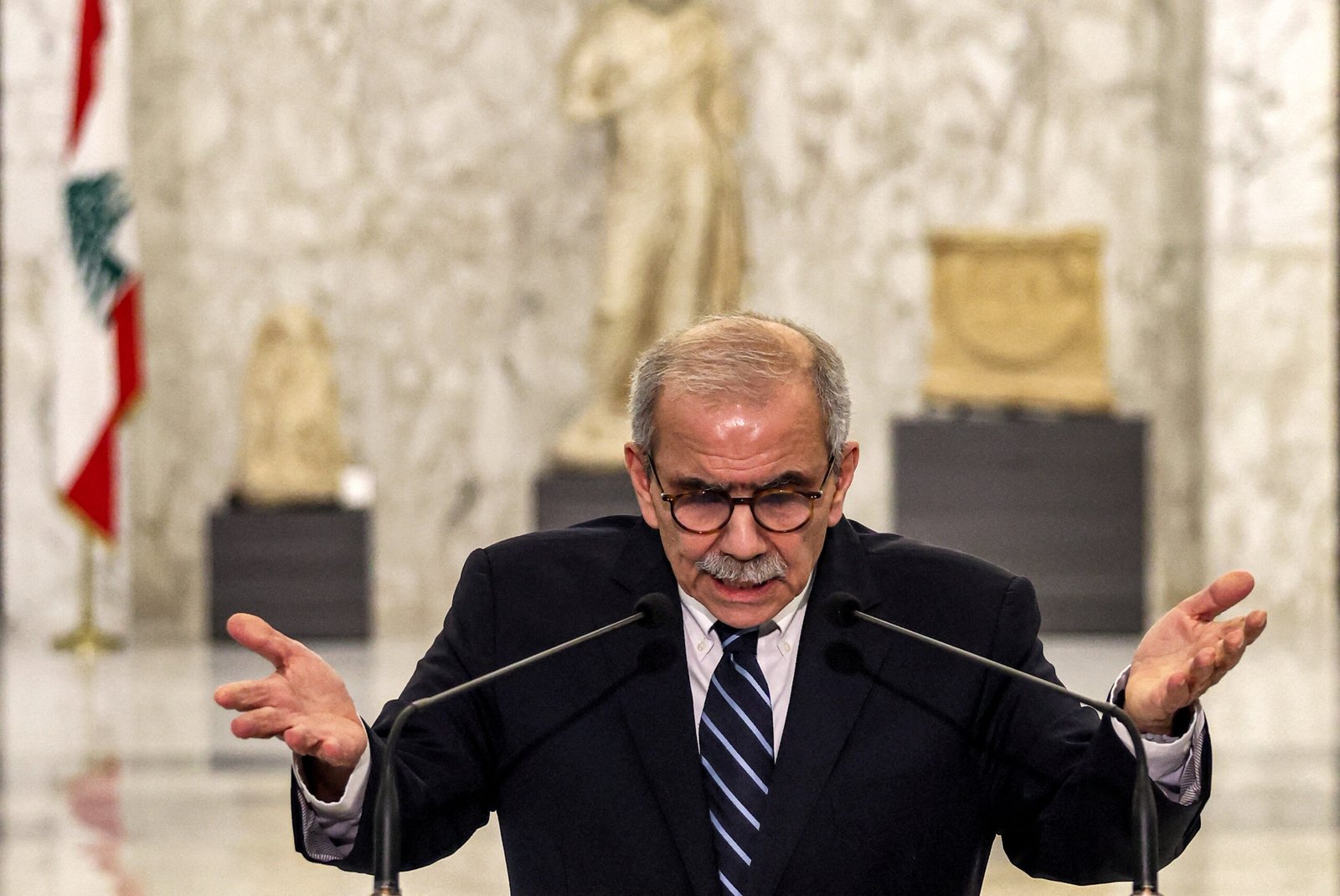

Less than a month after his surprise nomination to become Lebanon’s prime minister, Nawaf Salam attended his first cabinet meeting with his new ministers and recently elected Lebanese President Joseph Aoun at the presidential palace. After two years of a caretaker government and institutional paralysis, Lebanon finally has a new cabinet with a legal mandate to actually govern.

It took Salam weeks of consultations with various political parties and groups that make up Lebanon’s parliament and representative bodies to form his government. He faced many obstacles, chiefly from lobbyists working on behalf of the banking sector that have been resisting any financial reforms since the country’s financial collapse, as well as Hezbollah and the Amal Movement, Lebanon’s two Shiite political parties. These two parties were the only legislative representatives that refrained from nominating him during presidential consultations in mid-January.

In the lead-up to the cabinet formation, Salam faced various sources of public pressure and scrutiny. For instance, influential media personalities such as talk show hosts and siblings Marcel and Joseph Ghanem, fiercely attacked Salam and his deputy prime minister on national television for his potential financial restructuring plan that involves a fairer redistribution of losses and holding private banks accountable. Hezbollah and the Amal Movement insisted on maintaining control of the ministry of finance—a ministry held by a member of the Amal Movement since 2014—as well as naming all Shiite members of the government. Though the finance ministry ultimately did go to a former Amal MP, Yassin Jaber, the two parties did not get to choose every Shiite representative in cabinet.

For the first time since the Doha Agreement of 2008, the two parties will no longer be in possession of over a third of total cabinet seats which they had previously used to paralyze government proceedings. This concession at Doha came in the wake of Hezbollah militants storming Beirut on May 7, 2008, after the government decided the party should not have its own communications system running parallel to the state’s. Hezbollah and its allies had veto powers on all governments since, until its defeat and retrenchment in the wake of the last Israeli war on Lebanon.

These latest developments are both a testament to the political windfall and retreat Hezbollah finds itself in since the ceasefire agreement with Israel in late November. It is also a reflection of Hezbollah’s social and political squeeze with extensive regions in Lebanon’s south, east, and southern Beirut destroyed by the Israeli military and in dire need of financial aid for reconstruction and development. This is money that no international funder, be they Western or Arab, would be willing to pay should Hezbollah continue to hold sway over Lebanon’s politics and should economic reforms not be made.

Beyond the political circumstances that helped shape Salam’s government, and despite the 30-day wait and hand-wringing over its formation, the cabinet is now finally in power, though it has inherited a dire mess. The country is reeling from a deep financial crisis, the aftermath of the Beirut Port explosion, decades of political and economic mismanagement largely characterized by sectarian elites swooping public funds for their own enrichment while the country’s infrastructure deteriorates, and finally a devastating year-long Israeli war that has decimated, displaced, and impoverished hundreds of thousands of the country’s inhabitants. Not to mention that this has resulted in Israel still occupying land in South Lebanon and carrying strikes at will.

Salam and his cabinet have plenty to do and need to hit the ground running in order to shape any modicum of a better future for those residing in the country. With these issues come an array of priorities the government should address, ranging from the political to the financial.

The new government must ensure the full implementation of United Nations Resolution 1701—which ended the 2006 war with Israel—and its updated version, upon which the latest ceasefire between Israel and Hezbollah stands. This includes the complete withdrawal of Israel forces from all Lebanese territory.

Though the ceasefire between Hezbollah and Israel was signed over two months ago, Israel has violated the terms of the agreement hundreds of times. Israeli troops were due to fully withdraw on February 18, after it had already managed to push for an extension of the deadline once. Though Israel pulled out from villages it occupied in South Lebanon, it kept its troops posted in “five strategic positions in the area” for the foreseeable future—an unacceptable and untenable move.

Israel has been emboldened by Hezbollah’s military setbacks and the unflinching support from the United States, acting with impunity in southern Lebanon without any real repercussions. Salam has to press his case to both the United Nations, the United States, and other countries acting as guarantors for the ceasefire agreement.

Lebanese citizens from the south are eager to return to their villages, check on their homes, bury their dead, and begin reconstruction. Their right to return and to a dignified life are fundamental human rights, and the government must make every effort to ensure full Israeli withdrawal from all Lebanese land.

The cabinet must enact a series of financial and fiscal reforms which prioritize Lebanese citizens and ensure the recovery of their deposits. It also needs to push for the restructuring of the banking sector with regulations to prevent the activities which led to its collapse in the first place from happening again. These reforms will be key for Lebanon to receive any bailout of funds for broader reconstruction.

In his first televised interview since forming his government and in contradiction to the main strategy of the Lebanese authorities so far, Salam strongly implied that he would not resolve the financial crisis through further dilution or non-recovery of people’s deposits. Since Lebanon’s financial crisis erupted in 2020, depositors have been unable to withdraw their money as the currency grossly depreciated in value. One way the banks and the state have been trying to shift the debt they owe to depositors is by allowing measly monthly withdrawals from their deposits at the pre-crisis rates, effectively diluting deposits and the debt owed to people. Salam has hinted that this will no longer be the case and that people’s deposits are to be protected and returned—a move that will put him on a collision course with private banks and their political allies.

Political bickering along this front was clear during the cabinet formation process. The fight with the private banks will be the centerpiece of Salam’s mandate. Whatever he manages to achieve during his stint as prime minister will be determined by how much he forces the banks and political elites to pay for their responsibility of the financial crisis; nothing will matter more.

The new government must focus on securing funding for reconstruction and ensuring a just and non-sectarian rebuilding. No international donor across the geopolitical spectrum is willing to loan or donate any funds for Lebanon’s reconstruction without a sense of confidence in the Lebanese financial and political sectors, making financial reforms an absolute necessity.

The displacement and casualties of thousands of Lebanese caused by the Israeli military over the last year has wrecked large swathes of urban landscape, agricultural land, and public works infrastructure in the country, particularly in regions with strong Hezbollah support. The party is isolated and unlike 2006, Iran, its regional backer and funder, cannot come to its aid or send funds for reconstruction given the country’s own fiscal dilemmas, as well as American and Gulf vetoes on any further Iranian intervention in Lebanon’s future.

Salam and his cabinet have to enact a transparent reconstruction process that uplifts and centers the needs of locals, while maintaining a geopolitical balance without jeopardizing Lebanon’s financial recovery. Salam must also reiterate a political vision where the country is not simply doomed to switching from one geopolitical sphere to another while absorbing the shocks of these changes. Given the weakness of Hezbollah and the temporary retreat of sectarian elites from direct governing, this is a real opportunity for Salam to engage international donors and actors, and seek cooperation based on shared values that promote Lebanon’s sovereignty and interests.

On a bureaucratic front, the new government needs to protect judges, enact judicial reforms, and prevent the weaponization of the judiciary and security agencies against journalists. Historically, Lebanon has had some of the strongest civil liberties and press protections in the Arab world, however, civil liberties have increasingly been stifled for over two decades now. Since the financial collapse, the state of civil liberties has become even more precarious, such as the recent lawsuits against independent media platforms like Megaphone and Daraj by bankers with ties to sectarian elites.

A major factor leading this kind of repression is the increased politicization of the judiciary. More often than not, the judiciary has acted as the enforcer of sectarian and business elites seeking to stifle dissent, imprison journalists investigating corruption, and intimidate activists challenging the status quo.

Salam, as former president of the International Court of Justice, knows first-hand how imperative a just and egalitarian justice system is in a country. Lebanon’s post-civil war system of governance was built on the lack of accountability and dismissal of the judiciary. Any serious political reforms must prioritize a free and independent judiciary.

Overtures to the new regime in Syria

In a critical development since the ceasefire between Israel and Hezbollah was brokered, the Assad regime in Syria is no more. The Lebanese government should seize this opportunity to establish new relations with the Syrian state whose current head, Ahmed Al-Sharaa, has acknowledged the devastating toll the previous regime has caused in its interference in Lebanese politics for decades. The liberation of Syria from the Assad regime offers the potential for a new era of partnership and prosperity between Syria and Lebanon, based on mutual trust, respect of each country’s sovereignty, and the benefit of both nations’ peoples.

These reforms are a tall order for any newly incoming government, let alone for a state reeling from decades of financial and political crises, facing the aftermath of a devastating war. But Salam’s governmental mandate ends in May 2026 when the next parliamentary elections take place—a very short mandate to accomplish such huge tasks. Nevertheless, this is probably the first Lebanese government in the country’s history whose prime minister and a sizable portion of its cabinet have the ability to operate and practice politics in a different manner to the country’s traditional sectarian logic.

Despite the challenges and obstacles facing Salam today, the new prime minister can offer a break from the decades of rank corruption, mismanagement, and lack of accountability that have become the norm for Lebanese politics for half a century. This is an opportunity for serious reform that could set Lebanon on the road to broader structural changes and maybe even a brighter future.

Zeead Yaghi is a Nonresident Fellow at TIMEP focusing on governance, politics, and economy in Lebanon. He is also the institute’s second Mohamed Aboelgheit Fellow.