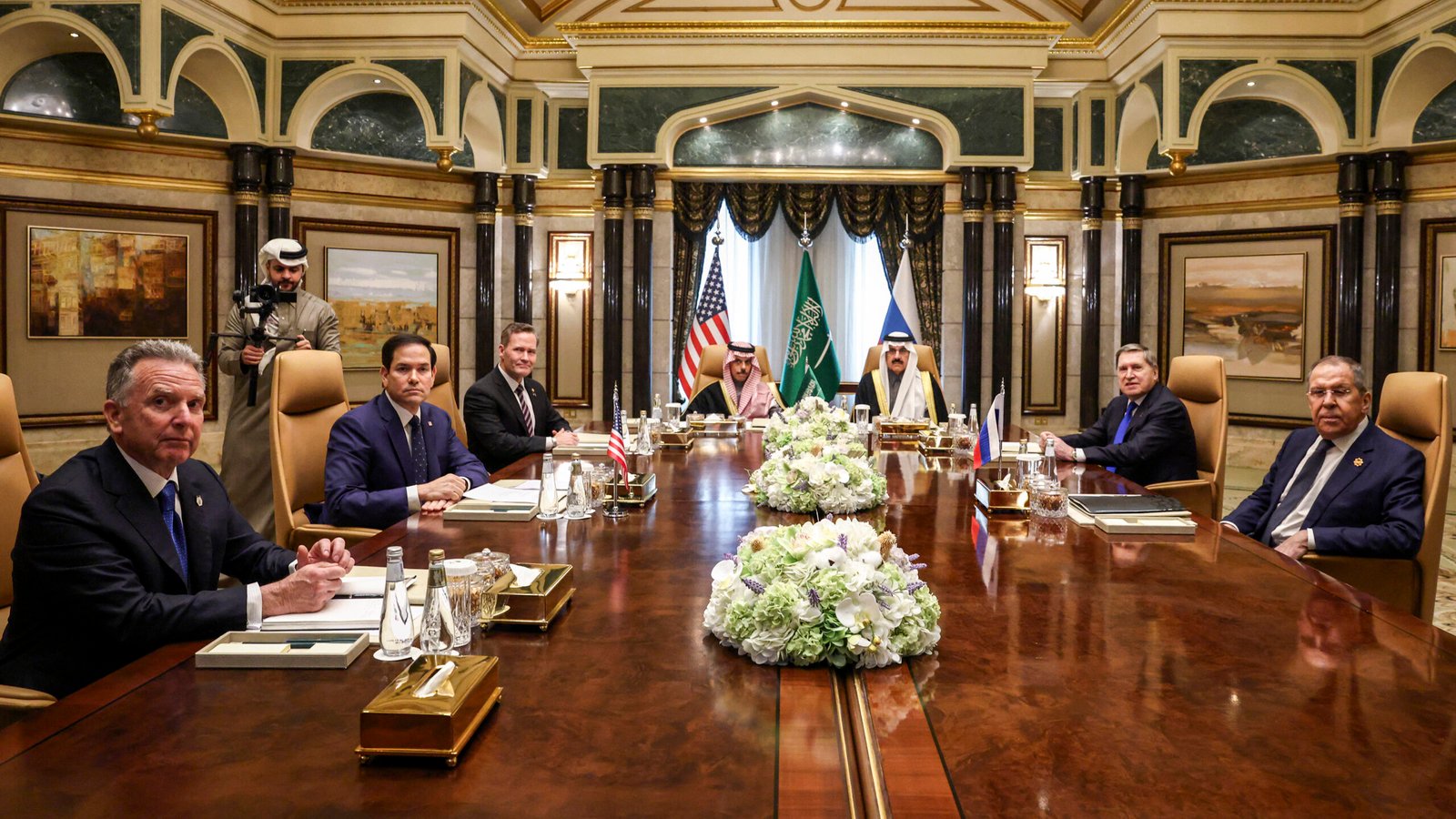

Beyond the headlines and the heartache, the Trump team is charting a course that is as bold as it is risky in relation to Russia and Ukraine. The private calls to Putin and dialogue in Saudi Arabia are likely not just about ending the war in Ukraine. These talks pivot around striking a new grand bargain linked to a mix of geopolitical spheres of influence and cross-cutting issues from access to natural resources to twenty-first-century arms control, which involves not just nuclear concerns but competition in space and cyberspace. In other words, the president’s foreign policy team appears to be leveraging negotiations around Ukraine as a forum to negotiate remaking the international system. The theory of victory is simple and seductive: use a grand rapprochement with Russia to undermine the authoritarian axis linking Moscow to China, Iran, and North Korea while advancing U.S. economic interests.

With great risk comes great reward and a need to take stock of the role of similar grand bargains historically. A cursory review of other major diplomatic pushes at the end of major wars provides more caution than cause for celebration. There is a long history of states seeking grand bargains at the end of wars to recalibrate the international system. These diplomatic pushes tend to involve pivots in a long-term strategy that result in famous treaties—think Westphalia in 1648, Utrecht in 1713, and Vienna in 1815. The bargains also cluster around long-term competition and recurrent conflicts in which statesmen use secret trips and high-stakes diplomacy to change the balance of power, as seen in Henry Kissinger’s famed trip to China in 1971, Carter’s secret shepherding of Arab-Israeli negotiations at Camp David in 1978, and Neville Chamberlain’s ill-fated trip to Munich in 1938.

In all instances, while wars end and crises are averted, underlying struggles over power persist. Great powers have great interests and rarely are willing to sacrifice them even when they are exhausted by conflict. This means any grand bargain with Russia should be weighed both in terms of its short-term benefit and long-term risk. And while it is impossible to predict the generational impacts of grand bargains—would Kissinger still go to China in 1971 if he read about the Chinese Communist Party in 2025—it is possible to assess the opportunity costs and likely tradeoffs the latest grand bargain foretells.

First, land for peace is more likely to buy a temporary armistice than long-term stability. Territorial concessions at the end of the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895, enshrined in the Treaty of Shimonoseki, sowed the seeds of future wars in Asia and the rise of a more militaristic Japan in the twentieth century.

Asking Ukraine to give up territory will gain favor in Moscow but at the cost of acerbating other territorial disputes in the Baltics and Caucasus. Furthermore, the Russian economy has become essentially a wartime economy, meaning an end to war is not an end to the business of war. As a result, even if Moscow gives security guarantees to Ukraine, which are backed by European troops, it won’t necessarily stop their agents from continuing hybrid attacks in Europe, global cyber operations targeting U.S. interests, and a sustained conventional military buildup. For the grand bargain to work, Trump will have to trust that Putin won’t use the end of hostilities in Ukraine to accelerate rearming. In the worst case, Putin could wait until Trump’s presidency ends to launch a new war, potentially timed with a major Chinese action against Taiwan.

Second, using peace in one region to gain security in another is a hard strategy to pull off. When Chamberlain was in Munich, he still had an eye on Asia. Japan had given notice in 1934 that it was exiting the Washington Naval Treaty, a twentieth-century maritime arms control convention. This meant the British Empire had to respond to not one but two regional powers seeking to challenge the status quo during the Great Depression. Chamberlain gambled that the uneasy settlement he brokered in Munich would buy time for the United Kingdom to prepare for global conflict.

Seeing peace negotiations surrounding the end of the war in Ukraine in this light shows the enduring challenges of global powers constrained by debt. Neither the British Empire in 1938 nor Pax Americana in 2025 can use debt alone to buy deterrence. Hard choices are required to set strategic priorities, and time horizons are always uncertain.

This reality is why the negotiations around the war in Ukraine must involve Kyiv and key European partners. The comparative advantage of the United States—compared to all other great powers historically—is its network of alliances. Yes, that means compromises and concessions, but it also means reducing costs so U.S. leaders can prioritize where to apply power globally to advance American interests. Even the perception of leaving Europe and Ukraine out risks undermining this advantage and, by extension, increases the costs and risks of a grand bargain. It also sends a dangerous message to other treaty partners in Asia that it is necessary to contain China. President Trump is right to put America first, but it doesn’t have to come at the expense of sacrificing long-term partnerships and strategic advantage.

While Trump’s team should be bold and define a new grand strategy, failing to take stock of the history of grand bargains to calibrate its diplomatic approach increases the risk the gambit fails, and the United States finds itself more insecure. For every Kissinger in China, there is a Chamberlain in Munich and cold wars turned hot due to strategic overconfidence.

Benjamin Jensen is a senior fellow in the Futures Lab at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C.