“Cinema affects you, whether you like it or not,” said the filmmaker Payal Kapadia, whose latest film All We Imagined as Light made waves in India and abroad recently. She was attending a session among the many participants at Delhi’s Asian Women’s Film Festival (AWFF) on March 8. Kapadia was one of many women filmmakers who showcased their films at the marquee film festival that has just turned 20.

For two decades, the AWFF has been a powerful platform for women’s voices in cinema, bringing together stories that challenge, disrupt, and redefine narratives. Organised by the International Association of Women in Radio and Television (IAWRT), the festival took place on the weekend of Women’s Day, from March 6 to 8. Over the years, it has grown into a vital space for filmmakers across Asia to showcase their work and push the boundaries of storytelling. It remains the only non-commercial film festival in the country, committed to fostering independence and experimentation in filmmaking.

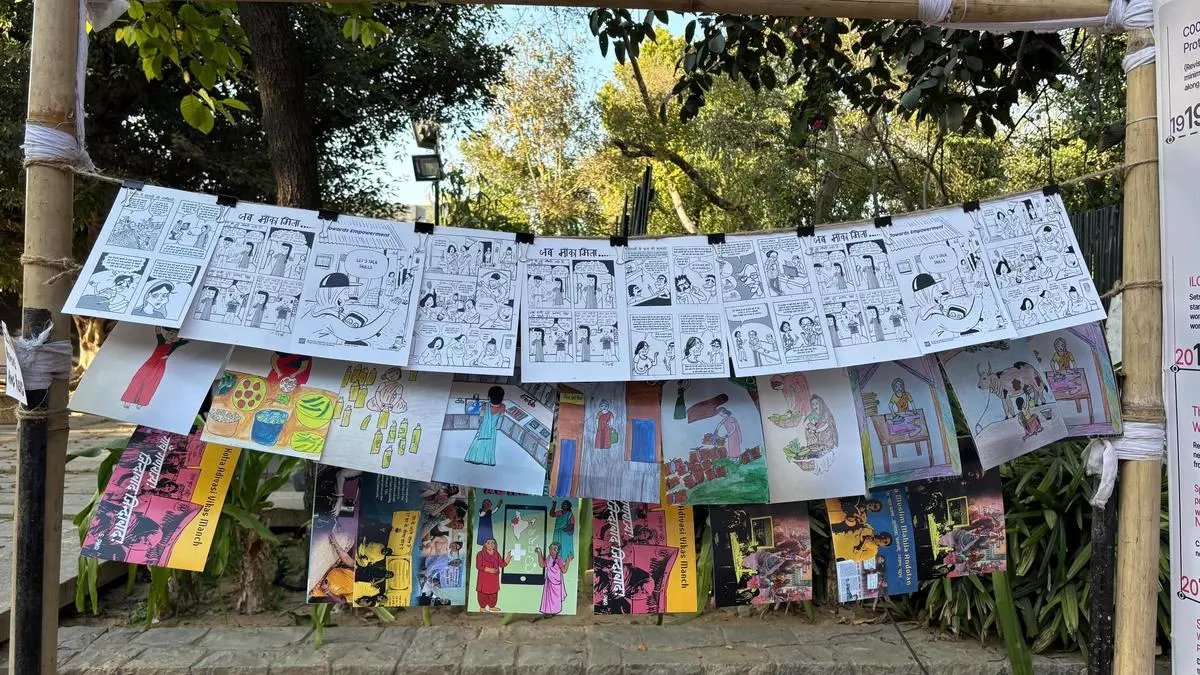

This year’s edition featured conversations on gender, climate, and archiving, among other pressing topics. The archival exhibition brought together personal and institutional histories, with contributions from organisations like Zubaan, Khabar Lahariya, and Jagori, alongside a panel discussion with personal archivists such as feminist historian Uma Chakravarti, visual artist Baaraan Ijlal, author Surya Nandini, and Instagram artist Siddhesh Gautam, better known by his social media handle @bakeryprasad.

Archiving memories and amplifying voices

The exhibition, titled “Memory as Movement,” celebrated the journeys of ten Delhi-based feminist organisations. “The challenge of archiving an institution like ours is that it exists in the memories of those who have built it. How do you tell that story? What pieces do you preserve? This was the question that shaped our exhibition and panel discussions,” noted Deepika Sharma, filmmaker and board member of the IAWRT, who curated the exhibition.

Also Read | Manipur Film Festival: Moments of truth and hope amid turmoil

Bina Paul, the festival director, shared insights into the thought process behind curating this year’s lineup. While AWFF does not work with a predefined theme, she observed that one often emerges organically. “Finally, the bottom line becomes the same. Women in Iran facing political oppression, girls across the world, and in India, navigating systemic challenges—what we saw this time was women finding their voices in various ways,” she said.

The filmmaker Payal Kapadia (right) discusses her film A Night of Knowing Nothing at the Asian Women’s Film Festival. | Photo Credit: Vitasta Kaul

AWFF has also worked to create mentorship and educational opportunities for budding filmmakers. “IAWRT offers fellowships like the Jai Chandiram [Memorial] Fellowship and the Padma Jha Shaw Fellowship. This year, we introduced the Manjira Dutta Fellowship for a budding documentary filmmaker. We also conduct outreach programmes—last year, we worked with tribal girls, and this year, we held a workshop for young women from areas around Delhi,” Bina Paul said, referring to the mobile film workshop hosted by IAWRT in collaboration with Delhi Tourism, where women from the outskirts of Delhi made films that were screened at the festival’s opening ceremony.

On the festival’s broader impact, Paul acknowledged that while a three-day event alone cannot radically transform the industry, it plays a crucial role in exposure. “Some efforts are being made, and we have seen an increase in filmmakers from marginalised communities. But whether women find it easy to pick up the camera and sustain filmmaking as a career remains an ongoing challenge,” she said.

The festival showcased a diverse range of panels, films, and documentaries from across Asia, including works from Afghanistan, Qatar, Iran, South Korea, and Syria, among others. Films from the Seoul International Women’s Film Festival (SIWFF) were presented by programmer Hei-Rim Hwang, who spoke about the evolving filmmaking landscape. While more women filmmakers are emerging, she noted that gender barriers continue to exist.

“Back in 1997, when the South Korea Women’s Film Festival began, there were only about seven well-known female directors or filmmakers actively working in the industry. Now, that number has grown significantly, with around 40 to 50 women filmmakers releasing new films each year,” she said. “It’s still difficult for women filmmakers to helm big blockbuster films. If we take a budget of over three billion Korean won as the benchmark, it becomes clear that women rarely get the opportunity to direct such large-scale projects.”

Programmer Hei-Rim Hwang introduces films from the Seoul International Women’s Film Festival (SIWFF) at AWFF and discusses the increasing participation of women filmmakers in South Korea. | Photo Credit: Vedaant Lakhera

Hwang also emphasised the importance of a physical space like a film festival to find the right audience. “I think other than commercial films, festivals can still be the channel to reach audiences and let the world know that these films exist and this part of life or these issues exist around the world. We always talk about diversity, but it’s hard to actually feel that. I think one of the main reasons that film festivals are still working is that they make you travel around the world, understand different types of lives, and hear unheard voices,” she said.

Cinema and politics

The festival also showcased documentary films from Rough Edges, an initiative by Ridhima Mehra and Tulika Srivastava to support films exploring diverse, intersecting realities. “We commissioned 10 films that explored multiple experiences of gender from lived perspectives. For us, what was very important was the focus from which these films are being made because there is a certain authenticity that comes from speaking for yourself, the communities you belong to, and the context you belong to. And for us, that is primary to creating films that are political and radical,” Srivastava said.

AWFF has deliberately kept its distance from corporate funding and relies on donations to function. “Look, it’s not easy. I’m not going to sugarcoat it, because it isn’t. Every year, we question whether we’ll be able to pull off the festival. But we all firmly believe in the importance of our independence. We don’t want our work to be compromised, and so far, we’ve managed,” said Managing Trustee of IAWRT, Aparna Sanyal.

On the final day of the festival, Kapadia’s A Night of Knowing Nothing was screened. The film, which was selected for the Directors’ Fortnight section at the 2021 Cannes Film Festival, is underpinned by the currents of the student protests that emerged post-2014, including one led by Kapadia herself during her days at the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII).

Also Read | How the Indian Film Festival Bhubaneswar celebrates resistance through cinema

On her time at FTII and the impact of the student strike, Kapadia said: “I think the strike was a moment for me that really changed the way I thought about the world and myself in it. I started thinking very differently, but also, like, the kind of faculty we would have and the films we would watch—it all shaped my politics. Cinema affects you, whether you like it or not, and a space like FTII, with its diversity and intense discussions, was crucial in that transformation.”

The discussion that followed touched upon Kapadia’s influences beyond cinema, the significance of exploring relationships in the current political context in her writing, and her fascination with blending documentary filmmaking with fictional narratives.

For the festival’s future, Paul stressed the importance of survival. “There are very few spaces where you get to see these films. AWFF is free and accessible, and we hope more people come to watch and engage. For many of these films, people always ask, ‘Where else will we see them?’—and the truth is, they won’t. This festival is that rare opportunity,” she said.