The newly re-elected US President, Donald Trump, declared last week that his first trip abroad in office might be to Saudi Arabia, even though US presidents traditionally make their first diplomatic visit to the United Kingdom. The unconventional leader in the Oval Office had already broken this tradition in his previous term when he first visited Riyadh. Trump added that he would once again diverge from convention if he could reach a trade agreement with the Arab kingdom worth $450 to $500 billion.

This statement was preceded by a phone call between the newly inaugurated president and Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, who pledged to expand trade with the US and invest $600 billion “or perhaps even more” in the American economy over the next four years. This suggests that Trump’s planned visit is likely to materialize.

The extended Trump family has longstanding business interests in Saudi Arabia. The Trump Organization is expected to build hotels in the kingdom, Saudi business partners are promoting extensive projects with the organization in other countries, and the president’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, has secured investments worth approximately $2 billion from Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund.

The rulers in Riyadh, who are well-versed in large-scale economic investments, including leveraging them for political gain, are already jumping on the bandwagon of the new US president and will undoubtedly continue to align with him swiftly. They aim to use this momentum to expand their economic and diplomatic foothold in Washington, thereby elevating their status in the region and worldwide.

For his part, Trump is eager to bolster Saudi Arabia’s regional standing, particularly by reviving the normalization agreement between Riyadh and Jerusalem. This deal had been on the table before the war with Hamas, but the Biden administration failed to secure it. The new White House administration sees such an agreement as a potential solution to several pressing Middle Eastern issues, including the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the war in Gaza. In recent days, progress seems to have been made on this front, and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s visit to Washington this week may focus on this matter.

Meanwhile, the convergence of interests between Riyadh and Washington, driven by their mutual desire to strengthen ties and potentially shape a new regional framework, is occurring alongside another significant trend in the Middle East: the decline of Iran and the Shiite axis it led, along with some of its key proxies.

Since the outbreak of the Swords of Iron War, Hamas has lost most of its leadership, its military capabilities have been significantly reduced, its weapon stockpiles have dwindled, and Gaza has been left in ruins with no clear path to reconstruction. Hezbollah has suffered a crushing blow in Lebanon, its leadership has been decimated, and its political power has weakened as a result. In Syria, Bashar al-Assad’s regime – an Iranian ally – has been ousted, and even in Iraq, efforts are underway to curb the power of Shiite militias backed by Tehran.

These developments have eroded Iran’s power and influence throughout the region. While grappling with deep economic crises and internal social challenges, Iran has watched as its various proxies, cultivated for the fight against Israel, have fallen like dominoes. The Islamic Republic itself has been targeted twice by Israeli Air Force strikes on its own soil and has been unable to effectively respond. At the same time, speculation that Trump may launch a maximum pressure campaign against Iran, though this has not yet materialized, further isolates the Ayatollah regime.

As Iran retreats, several actors are stepping in to shape the region’s future. Israel is, of course, one of them, though it has primarily operated in the military sphere. Other key players include Egypt and Qatar, both vying for influence in post-war Gaza, and Turkey, which is leveraging its influence over the rebel faction that has taken control of Syria to advance its war against the Kurds and strengthen its grip on the country.

Saudi Arabia, too, is seizing this opportunity. It seeks to capitalize on the decline of the Shiite crescent to establish itself as a leading regional force, this time at the head of a Sunni bloc whose interests and goals may be significantly different from those of Tehran.

A new chapter

Syria has broken free from over 50 years of Assad family rule, thanks to the Turkish-backed Hayat Tahrir al-Sham rebel group. Without Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s support, the rebels might not have been able to seize control of the country so swiftly. However, despite the rebels’ ongoing ties to Ankara, the first destination of Syria’s new foreign minister was not the Turkish capital, but Riyadh.

“We seek to open a new and bright chapter in the history of Syria-Saudi relations, one that reflects our shared past,” stated Asaad Hassan al-Shibani, Syria’s new foreign minister. He arrived in the kingdom at Riyadh’s invitation and spent his visit giving interviews advocating for the removal of sanctions on Syria following its regime change.

Al-Shibani’s choice to push this narrative in Riyadh was no coincidence. Shortly after Assad’s ouster, Saudi Arabia began pressuring world powers, especially the European Union, to change their policies toward Syria’s new regime. In mid-January, Riyadh hosted an international conference of European and Middle Eastern diplomats to discuss Syria’s future, publicly calling for the lifting of sanctions on Damascus. The kingdom pledged to help Syria’s new government stand on its feet and quickly began an airlift of humanitarian aid to the country.

Meanwhile, Syria’s new strongman, Ahmed al-Sharaa (or Mohammed al-Julani), who last week officially appointed himself president, dismantled armed factions, and dissolved the Baath Party, knows where his bread is buttered. In an interview with Al Arabiya, the Saudi news channel, Syria’s new president praised Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s Vision 2030 initiative and expressed enthusiasm about attracting Saudi investments. He also reassured the Gulf states that Iran no longer poses a threat in Syria. “Saudi Arabia will play a significant role in Syria’s future,” he emphasized, recalling that he spent his early childhood in Riyadh and would be happy to visit again.

The rapprochement between the two countries is particularly significant given their relations during Assad’s rule, which experienced far more downturns than upswings. Even before the Arab Spring, tensions were evident between Assad’s regime and the Saudi kingdom, due in part to Damascus’ support for Iran, particularly in connection with the assassination of Rafik Hariri in Lebanon. A brief reconciliation attempt in 2009 did not last, and relations between the two countries quickly deteriorated again.

The uprisings that erupted across much of the Middle East in 2011 were not welcomed by Riyadh’s rulers, but in Syria, they supported the rebels, again, largely due to their strained relations with Assad and their desire to curb Iran’s influence in the country, which was seen as a regional rival. Thus, despite Saudi Arabia’s general reluctance to encourage elements that destabilized the regional order, it found itself aligning with several Syrian opposition groups. However, it was careful to distance itself from factions associated with the Muslim Brotherhood and al-Qaeda, preferring to support more secular or nationalist groups.

The disconnect between the two sides remained largely unchanged until about two years ago. The fact that Assad remained in power despite more than a decade of rebellion, the desire to use reconciliation with him to get closer to Iran, and the necessity of cooperating with Damascus to combat drug smuggling into the kingdom, all these factors contributed to a gradual thaw in relations between Saudi Arabia and Syria. Meanwhile, Russia, which had previously been the dominant and most powerful player in Syria, became preoccupied with its war in Ukraine, leaving the Syrian arena primarily in Iran’s hands. Determined to prevent Tehran from becoming Assad’s sole and primary backer, the Saudis sought rapprochement with his regime.

The fall of the Alawite dictator’s regime suddenly presented the Saudi leadership with an entirely new opportunity. Within a short time, they gained access to a new government eager for their support, one that explicitly sought to expel Iran from Syria entirely. The threat of Captagon drug smuggling significantly declined, as did concerns about a new wave of refugees. On the surface, everything seemed set for Saudi Arabia to make a full-scale entry into Syria.

However, for now, the Saudis appear to be exercising patience and caution. One possible reason is their concern over the Islamist background of the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham organization and the possibility that it might promote a jihadist ideology within Syria and beyond. The way the new regime stabilizes itself, the policies it adopts, and the laws it implements will all play a crucial role in shaping Riyadh’s future relationship with Damascus. The disbanding of armed factions last week was a step in the right direction.

Still, Saudi Arabia has much to gain from Syria in the current period. Therefore, despite its cautious approach, Riyadh is likely to become involved in numerous initiatives in the country. Among other objectives, the kingdom aims to prevent Turkey from dominating the Syrian arena, much like Iran did in Iraq after the fall of Saddam Hussein. The Saudis also want a significant stake in Syria’s reconstruction and redevelopment projects and seek to position themselves as a key supplier of oil, fuel, and potentially even natural gas to Damascus, which, until now, has relied on Iranian imports.

Reforms and aid

This situation is particularly interesting in light of a similar development in neighboring Lebanon, where Saudi Arabia has also found itself facing a new scenario filled with opportunities – something that just a few months ago seemed impossible. Riyadh has long harbored concerns over Hezbollah’s influence in Lebanon, and the two countries plunged into a major crisis in 2021. When a Lebanese minister criticized Saudi Arabia’s war against the Houthis in Yemen that year, the Saudis responded with severe punitive measures: they expelled Lebanon’s ambassador from Riyadh and halted all imports from Lebanon. For an impoverished country like Lebanon, this was a devastating blow, and all attempts since then to reverse the decision proved futile.

However, Hezbollah suffered a decisive defeat at the hands of the IDF in the war, its top leadership, including Hassan Nasrallah, was eliminated, and during the ceasefire with Israel, Lebanon reached an agreement to elect a president, a move that reshaped the balance of power in the country and significantly weakened the Shiite axis. Into this power vacuum stepped Saudi Arabia, which, together with Western nations, pushed for the election of Joseph Aoun, the Lebanese Army commander, to the presidency. This position, the most powerful and significant in Lebanon, had remained vacant for two years due to domestic political deadlock over who should hold the office.

Aoun, a member of the Christian community, was indeed elected with support from Shiite political forces in Lebanon, but it was clear that he was not their preferred candidate. Moreover, the Shiites suffered an even greater setback when Aoun appointed Nawaf Salam, the President of the International Court of Justice in The Hague, as prime minister. Salam’s appointment passed in the Lebanese parliament without the support of Hezbollah and Amal, which together form the Shiite bloc, and he was widely regarded as Saudi Arabia’s preferred candidate.

With Aoun as president and Salam as prime minister, Riyadh feels it finally has partners it can work with, leaders who prioritize the interests of Lebanon itself over narrow factional or external interests, particularly those of Hezbollah and Iran.

It is no surprise, then, that shortly after Salam was appointed prime minister, Saudi Arabia’s foreign minister visited Lebanon, marking the first visit by a Saudi minister to the country in 15 years. From there, Prince Faisal continued on to neighboring Syria. In Lebanon, he met with President Aoun and Prime Minister Salam, and afterward, he expressed his hope that “we will soon see real reform in Lebanon, a commitment to the future rather than the past, so that we can increase our involvement in the country.”

Prince Faisal’s emphasis on reforms was no coincidence. For years, Riyadh has conditioned all economic aid to Lebanon on economic, legal, and political reforms. Analysts explain that the foreign minister’s visit signals Saudi confidence that the appointments of Aoun and Salam have put Lebanon on the right track toward these reforms, paving the way for real and meaningful cooperation.

Another key focus was the diminishing influence of Iran. Analysts noted that without Hezbollah and Iran weakening in Lebanon, neither Aoun nor Salam could have been appointed, nor would Saudi involvement have been possible.

A further sign of Riyadh’s growing influence at Tehran’s expense in Lebanon came from an announcement by President Joseph Aoun. He declared that his first official diplomatic visit as Lebanon’s new leader would be to Saudi Arabia, where he is expected to sign dozens of economic and security agreements.

“Saudi Arabia is emerging as the great winner in the Middle East,” explained Lina Khatib, a Chatham House expert, to the Financial Times. “The major changes in Lebanon and Syria highlight Riyadh’s central role in the region. Neither country could have made these shifts without Saudi support.”

In the coming period, Saudi Arabia will need to assess the stability of both Lebanon and Syria and accordingly adjust its level of involvement and investment in these countries. If Syria’s new government stabilizes and develops the country, and if the Lebanon ceasefire holds without renewed clashes between the IDF and Hezbollah, it will be of utmost importance to Riyadh.

For example, Lebanese military cooperation with hostile elements in southern Lebanon last week was a troubling sign for Saudi Arabia. While Riyadh supported the IDF’s withdrawal from southern Lebanon, Aoun, as a former army commander, is expected to restrain Lebanese troops and ensure they do not get involved, even indirectly, in hostilities against Israel.

In this regard, Saudi Arabia’s interests align closely with Washington’s: to prevent Syria and Lebanon from being drawn into regional conflicts, particularly any potential continuation of the war in Gaza. Meanwhile, both countries are also highly motivated to prevent a renewed Iranian foothold and the resurgence of Tehran’s proxies.

Israel, for its part, should feel encouraged by Saudi Arabia’s involvement in both Lebanon and Syria. This window of opportunity, in which Riyadh is interested in advancing normalization with Israel and a strategic agreement with the US, could potentially lead to the formation of a new regional framework and new norms.

The Saudis, for their part, continue to declare their desire for progress on the Palestinian issue – whether this is a statement aimed at appeasing public opinion in the kingdom or a genuine interest of the Saudi leadership – but in Jerusalem, many believe that a mutually acceptable formula can be reached.

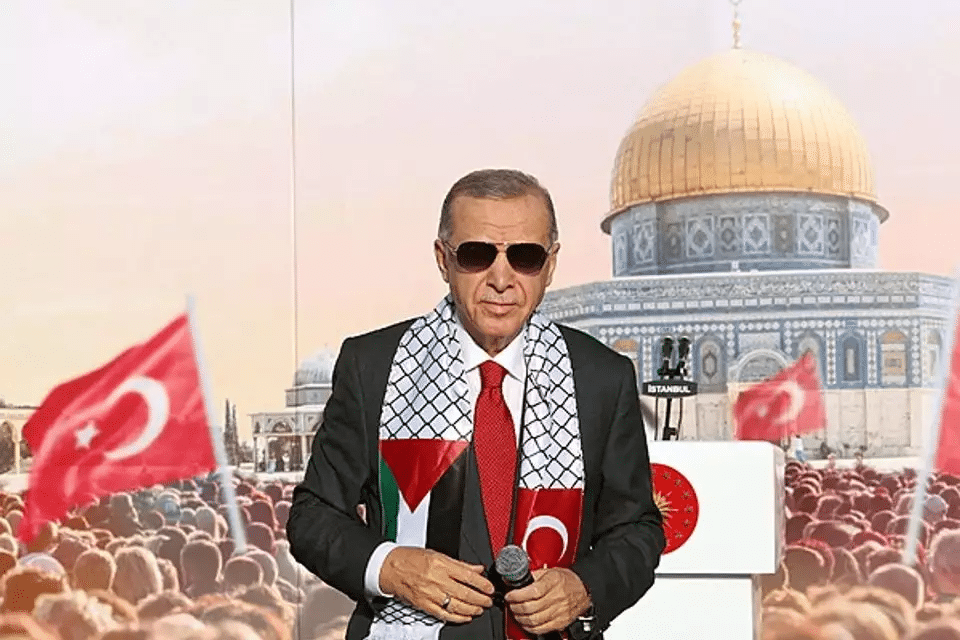

In any case, Saudi Arabia’s regional strengthening is far preferable to the alternative, namely, the entry of other nations, particularly Iran or other representatives of the Shiite axis. The same applies to so-called “moderate” Sunni players in the region, such as Qatar or Turkey, especially given that Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan declared last week his support for the “spirit of resistance” demonstrated by Hamas in its war against Israel.

From Israel’s perspective, as long as Saudi Arabia’s growing influence does not conflict with its security interests, it is important to encourage Saudi involvement in Lebanon and Syria. In any case, dialogue and negotiations with actors like Saudi Arabia should be prioritized over continuing engagement with regional players like Qatar, which has so far supported Hamas and the terrorism it generates.

Since this interest aligns with President Trump’s vision, Israel stands only to benefit from such a scenario.