As geopolitical tensions rise, African nations are increasingly aligning with Chinese President Xi Jinping’s Global Security Initiative. The framework, which promotes non-interference, respecting sovereignty, and development-focused security, is appealing to African countries as an alternative to Western-led interventions. Through military cooperation, peacekeeping missions, counterterrorism assistance, and non-conditional security aid, among others, China is deepening its strategic footprint on the continent, which also complements its Belt and Road Initiative. As Africa pivots towards China’s security vision, this shift challenges Western influence, reshaping global power dynamics on the continent.

On 5 September 2024, in his keynote at the 9th Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), Chinese President Xi Jinping stated:

“Modernization is an inalienable right of all countries. But the Western approach to it has inflicted immense suffering on developing countries. […] China and Africa’s joint pursuit of modernization will set off a wave of modernization in the Global South and open a new chapter in our drive for a community with a shared future for mankind.”[1]

Xi underscored China’s and Africa’s “modernisation” as “just and equitable, open and win-win”, “people-centred”, “diverse and inclusive”, “eco-friendly”, and “underpinned by peace and security”—characteristics often branded as the “China model”. At the same event, Xi set new precedents for China-Africa ties by elevating China’s bilateral relations with all African countries that recognise the People’s Republic of China (all 53 countries except Eswatini) to at least the “strategic level”, characterising China-Africa bilateral relations as an “all-weather China-Africa community with a shared future for the new era,”[a] proposing a new China-Africa trade and investment agreement, and committing to training African leaders.[2]

Over the past decades, China’s relations with Africa have grown significantly, driven by economic cooperation, infrastructure development, and diplomatic ties. Through initiatives like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the FOCAC, China has become Africa’s largest trading partner and a key investor in sectors such as mining, energy, telecommunications, and transportation. China follows a “non-interference” policy, offering loans and investments with fewer political conditions than those from the United States (US) or international financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund or the World Bank. China, unlike the West, also does not pressure African governments on issues like good governance, democracy, human rights, or political transparency, making it an attractive partner for many African nations.

As China’s footprint in Africa expands through trade, infrastructure, military cooperation, and other exchanges, its evolving role as a security actor or guarantor will shape the continent’s geopolitical landscape, raising both opportunities and challenges for African states and beyond. In this regard, particularly in the context of Xi’s Global Security Initiative (GSI), the question is why China wants to play a larger role in African security.

In April 2022, at the Annual Conference of the Boao Forum for Asia, Xi Jinping proposed the GSI (全球安全倡议) framework as a new approach to international security. It is one of three initiatives, alongside the Global Development Initiative (GDI) and the Global Civilization Initiative (GCI). In the context of global peace and stability, Xi proposed the “Chinese solution” to global security challenges, stating:

“Security is the precondition for development. We, humanity, are living in an indivisible security community. It has been proven time and again that the Cold War mentality would only wreck the global peace framework, that hegemonism and power politics would only endanger world peace, and that bloc confrontation would only exacerbate security challenges in the 21st century. To promote security for all in the world, China would like to propose a Global Security Initiative.”[3]

In the face of growing threats of “unilateralism, hegemony and power politics, and increasing deficits in peace, security, trust, and governance,” the GSI, in Beijing’s view, is “yet another global public good offered by China and a vivid illustration of the vision of a community with a shared future for mankind in the security field.”[4] In offering a fundamental solution to eliminating “the peace deficit” by contributing Chinese perspectives to meeting international security challenges, the GSI, according to Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Le Yucheng,[b] aims to:

“Take the new vision on security as the guiding principle, mutual respect as the fundamental requirement, indivisible security as the important principle, and building a security community as the long-term goal, in order to foster a new type of security that replaces confrontation, alliance, and a zero-sum approach with dialogue, partnership, and win-win results.”[5]

The GSI Concept Paper released in February 2023 says its goal is “to eliminate the root causes of international conflicts, improve global security governance, encourage joint international efforts to bring more stability and certainty to a volatile and changing era, and promote durable peace and development in the world.”[6]

Even before launching the GSI, Beijing had pledged to play an active role in maintaining world peace, security, and stability in various capacities, as outlined in the White Papers of 2014, 2014, and 2019 (see Table 2).

The above areas are outlined in the 2023 GSI Concept Paper, which emphasises security challenges such as terrorism, cybersecurity, biosecurity, transnational organised crime, public health, drug trafficking, nuclear proliferation, emerging technologies, AI and data security, climate change, and international policing.

In assessing Xi’s conception of the GSI, it becomes imperative to factor in the following key aspects:[10] first, the GSI was launched amidst rising insecurity and growing resentment towards China, starting with the COVID-19 pandemic and continuing over China’s position on the Russia-Ukraine war, against the backdrop of Beijing’s “no limits” friendship with Moscow.

Second, the elements of the framework convey a unified view that caters to China’s interests. For example, “respecting the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all countries” can be interpreted as respecting China’s sovereignty claims over the South China Sea, East China Sea, the Himalayan border with India, and Taiwan.[c] The phrase “non-interference in internal affairs” signals “non-interference” in China’s internal matters related to Xinjiang, Tibet, and Hong Kong.[d] Meanwhile, the statement “reject the Cold War mentality, oppose unilateralism, and say no to group politics and bloc confrontation” serves as a way of denouncing any minilateral or multilateral groupings that China is not part of, such as the QUAD and AUKUS.

What has also become characteristic of China’s involvement is its conflict mediation and peacebuilding efforts in alignment with GSI principles, such as proposing a ‘12-Point Peace Plan’ in 2023[11] and appointing a ‘Special Envoy for Peace Talks’[e] to mediate the Russia-Ukraine conflict,[12] brokering peace between Saudi Arabia and Iran,[13] and mediating between Palestinian factions amidst the recent Gaza conflict by signing the Beijing Declaration.[14]

With the GSI, China seeks to centralise its position as a world power within the reform process of global security approaches and mechanisms.

China’s interests in Africa are driven by four objectives:[15] first, politically, China seeks Africa’s support for its “One China” policy and its foreign policy agendas in multilateral forums such as the United Nations. Second, economically, China sees Africa as a source of natural resources and market opportunities. Third, from a security standpoint, political instability in Africa causes concerns for China’s strategic interests. Finally, China sees an opportunity for the success of the “China model” in non-democratic African countries (such as Zimbabwe, Sudan and South Sudan, Angola, and Rwanda), which indirectly supports China’s political ideology against Western democratic ideals.

In recent years, China’s role as a security guarantor in Africa has grown, driven by its strategic interests, economic investments, and deepening ties with African states. There is a clear trend of increased Chinese interest in and engagement with African security both directly and indirectly. For instance, in his keynote speech at the opening ceremony of the 2024 FOCAC Summit, Xi Jinping, pledging the “Partnership Action for Common Security”, declared:

“China is ready to build with Africa a partnership for implementing the GSI and make it a fine example of GSI cooperation. We will give Africa RMB1 billion yuan of grants in military assistance, provide training for 6,000 military personnel and 1,000 police and law enforcement officers from Africa, and invite 500 young African military officers to visit China. The two sides will conduct joint military exercises, training and patrol, carry out an “action for a mine-free Africa,” and jointly ensure the safety of personnel and projects.”[16]

To implement the 10 partnership actions, Xi promised that the Chinese government will provide RMB 360 billion in financial support over the next three years—RMB 210 billion in credit lines, RMB 80 billion in assistance in various forms, and at least RMB 70 billion in investment by Chinese companies in Africa.[17] China’s involvement in African security has significantly increased. For instance, since 2008, the Chinese military has dispatched 44 escort task forces to the Gulf of Aden and Somali waters and conducted joint anti-piracy exercises with countries like Nigeria and Cameroon, contributing to maritime safety and regional stability. Even before the launch of the GSI, China had actively participated in international peace conferences related to the Sahel, South Sudan, and the Horn of Africa.[18]

“China believes that the more turbulent the international situation is, the more difficulties and challenges Africa faces, the more we must pay attention to the voices of African countries and increase our support and assistance to Africa. As a good brother of African nations, China will continue to stand with Africa, firmly support Africa in maintaining peace and security, firmly support Africa in achieving economic recovery, firmly support Africa in defending its legitimate rights and interests, and make due contribution to Africa’s independence and sustainable development.”[19]

This highlights Africa’s special place in China’s GSI calculus, as evident from the GSI Concept Paper, which categorically mentions Africa among its 20 “priorities of cooperation”, stating:

“Support the efforts of African countries, the AU and sub-regional organizations to resolve regional conflicts, fight terrorism and safeguard maritime security, call on the international community to provide financial and technical support to Africa-led counter-terrorism operations, and support African countries in strengthening their ability to safeguard peace independently. Support addressing African problems in the African way and promote peaceful settlement of hotspots in the Horn of Africa, the Sahel, the Great Lakes region and other areas. Actively implement the Outlook on Peace and Development in the Horn of Africa, promote the institutionalization of the China-Horn of Africa Peace, Governance and Development Conference, and work actively to launch pilot projects of cooperation.”[20]

In addition, among the five “platforms and mechanisms of cooperation”, China aims to leverage two Africa-linked mechanisms: the China-Horn of Africa Peace, Governance, and Development Conference, established in June 2022, to promote regional and global peace and stability, and the China-Africa Peace and Security Forum, to deepen security-related exchange and cooperation.

The first meeting of the China-Horn of Africa Peace, Governance, and Development Conference was held in June 2022,[f] where China’s special envoy to the Horn of Africa,[g] Xue Bing, expressed Beijing’s interest to “provide mediation efforts for the peaceful settlement of disputes based on the will of countries in this region.” He acknowledged the “complicated and intertwined ethnicity, religion, and boundary issues” that could be “difficult to handle, as many of them dates back to colonial times.”[21] The second meeting was held in June 2024 in Beijing, where China’s Vice Foreign Minister Chen Xiaodong stated that China is willing to work with the Horn of Africa countries to turn the region into a “horn of peace, development, and prosperity”, working towards building a high-level China-Africa community with a shared future.[22]

Meanwhile, the China-Africa Peace and Security Forum provides a common platform for military officials from both sides to convene and discuss issues of mutual interest, serving two primary goals: consolidating strategic communication networks between Chinese and African defence departments and exploring ways to align African militaries and security architecture with China’s GSI.

For the most part, the security dimension of China-Africa cooperation has involved the deployment of troops for UN peacekeeping missions, training African military and security personnel, and conducting counter-piracy operations. However, in recent years, the scope has broadened to include conflict mediation, counterterrorism, policing and law-enforcement cooperation, and military training (see Table 3).

As per the above mapping, China’s engagements with Africa are primarily in five areas: UN peacekeeping missions, multilateral initiatives, arms sales and military cooperation, non-traditional security threats, and conflict mediation and resolution.

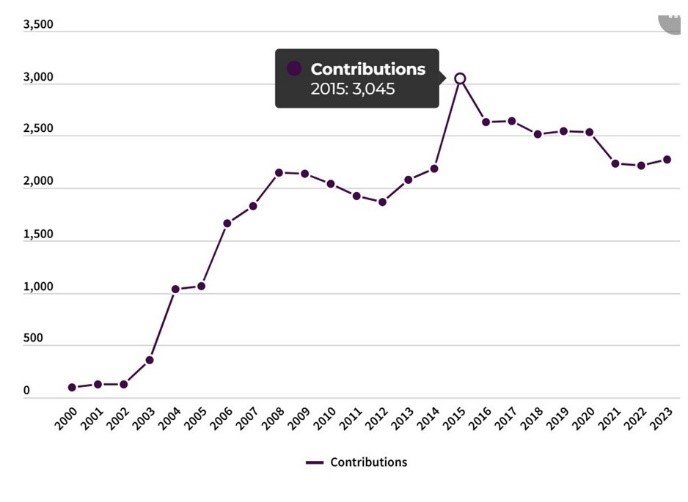

First, China has expanded its participation in UN peacekeeping missions (see Figure 1). Today, China is the 10th largest contributor of troops and police (with 2,274 personnel) and the second largest financial supporter (accounting for nearly 19 percent of UN peacekeeping programme funding),[h] providing more peacekeepers than all UN Security Council Permanent members combined.[23] In 2018, China established its Peacekeeping Affairs Centre. In 2020, Beijing issued a white paper on “China’s Armed Forces: 30 Years of UN Peacekeeping”, stating that “China’s Blue Helmets have become a key force in UN peacekeeping” and “China’s armed forces have expanded the composition of their peacekeeping troops from single service to multiple military branches”, with efforts “extended beyond conflict prevention to building lasting peace.”[24]

The UN currently runs 15 peacekeeping missions, with the majority in Africa, where China has actively participated (see Table 4). In highlighting China’s contribution to UN peacekeeping missions in the last 30 years, the 2020 white paper posits that China has:

“Contributed 111 engineer units totaling 25,768 troops to eight UN peacekeeping missions in Cambodia, the DRC, Liberia, Sudan, Lebanon, Sudan’s Darfur, South Sudan, and Mali. These units have built and rehabilitated more than 17,000 kilometers of roads and 300 bridges, disposed of 14,000 landmines and unexploded ordnance, and performed a large number of engineering tasks including leveling ground, renovating airports, assembling prefabricated houses, and building defence works. Twenty-seven transport units totaling 5,164 troops were dispatched to the UN peacekeeping missions in Liberia and Sudan. They transported over 1.2 million tons of materials and equipment over a total distance of more than 13 million kilometers. Eighty-five medical units of 4,259 troops were sent to six UN peacekeeping missions in the DRC, Liberia, Sudan, Lebanon, South Sudan, and Mali. They have provided medical services to over 246,000 sick and wounded people. Three helicopter units totaling 420 troops were sent to Sudan’s Darfur. They completed 1,951 flight hours, transported 10,410 passengers and over 480 tons of cargo in 1,602 sorties.”[26]

Second, China has further enhanced its military ties with Africa through arms exports, military training and education, and joint exercises. From 2019 to 2023, Africa’s major arms suppliers were Russia (24 percent), the US (16 percent), China (13 percent), and France (10 percent). With a 19 percent share of sub-regional arms imports, China surpassed Russia (17 percent) to become the largest supplier of major arms[i] to Sub-Saharan Africa.[27] Besides, at the 2024 FOCAC summit, Beijing pledged US$50 billion to Africa over the following three years, with US$140 million dedicated to security cooperation, including training 6,000 military personnel and 1,000 law enforcement officers, along with bringing 500 young African military officers to China for training. As part of its military diplomacy, China conducts the ‘Peace Unity’[j] joint exercise with Tanzania (Mozambique joined in 2024), a counterterrorism and counter-piracy drill, and ‘Exercise Transcend’ with Tanzania, a joint military exercise focused on the Marine Corps held in 2023.

In addition, China has played a mediation role in various African conflicts, including the Darfur region in Sudan in 2007; Zimbabwe, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Rwanda in 2008; South Sudan in 2013; and Djibouti in 2017. China also supported African Union-led mediation efforts in the Ethiopia-Tigray conflict from 2020 to 2022. In 2017, China established its first overseas military base in Djibouti to support anti-piracy operations and peacekeeping missions and to protect Chinese investments and citizens. For instance, scholars argue that the base in Djibouti plays a significant role in ensuring that China’s vision of a maritime sea route which is in line with its BRI is realised.[28] Furthermore, the 2021 Dakar China-Africa Action Plan 2022-2024, from the 8th FOCAC Summit, identified military and police cooperation, counterterrorism, and law enforcement as strategic priorities between China and Africa.[29] Additionally, China has expanded its network of defence attaches in Africa[30] as part of a broader strategy to increase its military and security cooperation with African nations.

Therefore, China’s security role in Africa has expanded from peacekeeping to that of military partnerships shaped by Beijing’s pragmatism. In linking the GSI to Africa, at the 11th Xiangshan Forum in 2024, Chinese Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs, Chen Xiaodong stated:

“In the Horn of Africa, in support of regional countries to tackle security, development and governance challenges, China has proposed and worked with these countries to step up the implementation of the Outlook on Peace and Development, mediated actively on hotspot issues and provided humanitarian assistance.”[31]

GSI complements China’s long-standing engagement with Africa, ranging from military cooperation (as discussed earlier) to trade and infrastructure development. With its expanding role as a UN peacekeeper, China has been able to establish a soft military presence in Africa, where it is primarily engaged in infrastructure investment and resource extraction. Besides, forums like the FOCAC serve as platforms where security and development goals, including those of the GSI, are integrated.

What stands out is that by making significant investments in Africa, China has surpassed the US, both in terms of volume and impact. China is Africa’s largest trading partner,[k] with China-Africa trade reaching a record high of US$282.1 billion in 2023, a 1.5-percent increase year-on-year.[32]

Figure 3: Africa’s Exports and Imports to China by Sector

In foreign direct investment (FDI), China is again the largest provider of FDI to Africa, roughly double the level of American FDI.[35] Additionally, China is by far the largest lender to African countries. In Africa’s total external debt,[l] China’s share grew from 1 percent in 2000 to 13 percent in 2022, given vast infrastructure lending to African countries.[36]

In 2003, the annual FDI flow from China to Africa was approximately US$75 million. By 2022, it peaked at US$5 billion, representing about 4.4 percent of the region’s total FDI. Since 2023, Chinese FDI flows to Africa have exceeded those from the US (see Figure 5). The top five African destinations for Chinese FDI in 2022 were South Africa, Niger, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Egypt, and Côte d’Ivoire.[38] In 2021, at the 8th FOCAC Summit, China committed US$10 billion in private FDI for the 2022-2025 period.[39] In 2024, at the 9th FOCAC Summit, China committed to providing Africa with RMB 360 billion in financial support over the next three years, including no less than RMB 70 billion in investments by Chinese companies.[40]

Figure 5: Chinese FDI Flow vs. US FDI Flow in Africa (2003-2022)

In 2022, the gross annual revenues of Chinese companies’ engineering and construction projects in Africa totalled US$38 billion, with Nigeria, Angola, Algeria, Egypt, and the Democratic Republic of Congo accounting for 41 percent of all Chinese companies’ construction project gross annual revenues in Africa.[43] Besides, China has made significant investments in Africa’s energy sector, aiming to promote the continent’s development (see Table 5) and ensure its resource security by making significant inroads into Africa’s mineral sector, particularly in the exploration and extraction of critical minerals (see Table 6).

Moreover, Africa is central to Xi’s BRI, with 53 African countries participating as of 2024.[m] The China Belt and Road Initiative Investment Report 2023 suggests that investments in Africa grew by an impressive 114 percent, totalling US$21.7 billion—a surge driven by China’s strategic investments, particularly in the port and shipping sectors, where construction contracts in Africa increased by 47 percent in 2023 alone.[44] In the port sector, China is the largest infrastructure construction player in Africa (as well as in most of the developing world). Estimates suggest that Chinese firms[n] held a 61 percent market share for such contracts in 2020, up from less than 10 percent in 2002.[45]

To summarise, China’s engagement in Africa’s peace and security agenda is driven by four main interests:[47] First, to protect its trade market and its investments, as most of China’s investments are in conflict-prone regions of the continent. Second, by playing an active role in Africa’s peace and security, China seeks to boost its image as a peacemaker and as a valuable actor in the global arena. Third is the domestic political imperative to protect its citizens abroad as, in Africa, Chinese nationals are engaged in various activities such as mining, construction projects, trade and others. Fourth, it also provides China with the opportunity to gain practical experience in dealing with emerging security threats and challenges in the global world.

China’s expanding security role in Africa is driven by its pragmatic choice to prioritise its economic and strategic interests. Beijing is aware that any instability in Africa would be detrimental to its trade and investments, including its BRI projects. In this regard, the GSI aligns with China’s desire to protect its economic interests in Africa, particularly investments in infrastructure and natural resources. This strategy also plays a key role in countering the West’s influence in the region and establishing China as the primary player in ensuring stability and security in Africa. With the GSI, China aims to position itself as a champion of world peace and security, in contrast to the existing US-led international order, by offering ‘Chinese solutions’ to world problems.

Given this, the GSI raises concerns about China’s intention and its impact on African countries. Whether Xi Jinping’s GSI can offer a ‘Chinese solution’ to Africa’s problems remains questionable. More crucially, it will test the ability of African countries to engage with China on their terms, prioritising their national interests. Therefore, only time will tell whether the GSI is just another Chinese rhetoric in the name of ‘shared destiny’.

Amrita Jash is Assistant Professor, Department of Geopolitics and International Relations, Manipal Academy of Higher Education (Institution of Eminence), Manipal, India.

[a] Until now, China used the phrase “all weather” only in characterising its ties with its ally, Pakistan.

[b] This idea was provided by Le Yucheng in his keynote speech at “Seeking Peace and Promoting Development: An Online Dialogue of Global Think Tanks of 20 Countries” in Beijing on 6 May 2022.

[c] China claims the South China Sea through its “nine-dash line” (upgraded to the ten-dash line in 2023), which overlaps with the sovereignty claims by the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Vietnam. On the East China Sea, China has a dispute with Japan over the Diaoyu islands (Senkaku islands in Japanese). On the Himalayan border with India, China has an unresolved boundary dispute along the Line of Actual Control. With regard to Taiwan, China sees it as a ‘renegade province’.

[d] Under its non-interference policy, China opposes foreign involvement in its internal matters, such as Xinjiang, Tibet, and Hong Kong, which China strictly treats as purely domestic matters and off-limits for foreign discussion or intervention.

[e] In 2023, China appointed Li Hui, who was China’s deputy foreign minister from 2008 to 2009 and served as China’s ambassador extraordinary and plenipotentiary to Russia from 2009 to 2019, as the Special Envoy for Peace Talks.

[f] According to the Joint Statement, the countries agreed to a peaceful resolution of regional problems, jointly address natural disasters, and uphold a coordinated approach to combat cyber security, terrorism, illegal arms, and human trafficking, among others.

[g] The Horn of Africa countries include Ethiopia, Kenya, Sudan, South Sudan, Somalia, Uganda, and Djibouti.

[h] While the US remains the largest financial contributor to UN peacekeeping efforts, it ranks 84th out of 123 contributing countries in terms of deployment of personnel.

[j] The Peace Unity 2024 marked the fourth joint military exercise between Tanzania and China, after exercises in 2014, 2019-20, and September 2023.

[k] China was Africa’s largest trading partner for 15 consecutive years until 2023.

[l] Africa’s debt stock to China includes Angola (US$6.69 billion), Zambia (US$5.73 billion), Egypt (US$5.21 billion), Nigeria (US$4.29 billion), Côte d’Ivoire (US$3.85 billion), Cameroon (US$3.78 billion), South Africa (US$3.43 billion), and the Republic of Congo (US$3.42 billion).

[m] The 53 countries include: Algeria, Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burundi, Cabo Verde, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Democratic Republic of Congo, Republic of Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Djibouti, Egypt, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Libya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Morocco, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, São Tomé and Príncipe, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Africa, South Sudan, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Tunisia, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

[n] The China Communications Construction Corporation (CCCC) has been by far the most prominent player in the African port construction space, winning contracts in at least 38 ports.

[1] The State Council, The People’s Republic of China, “Full Text: Keynote Address by Chinese President Xi Jinping at Opening Ceremony of 2024 FOCAC Summit,” September 5, 2024, https://english.www.gov.cn/news/202409/05/content_WS66d964bdc6d0868f4e8eaa07.html

[2] Christian-Géraud Neema, “What FOCAC 2024 Reveals About the Future of China-Africa Relations,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, November 21, 2024, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2024/11/what-focac-2024-reveals-about-the-future-of-china-africa-relations?lang=en

[3] Boao Forum for Asia, “Chinese President Xi Jinping’s Keynote Speech at the Opening Ceremony of BFA Annual Conference 2022,” April 21, 2022, https://www.boaoforum.org/ac2022/html/detail_2_486_15865_meetingMessage.html

[4] Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in Georgia, “Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Wang Wenbin’s Regular Press Conference on April 21, 2022,” April 21, 2022, https://ge.china-embassy.gov.cn/eng/fyrth/202204/t20220421_10671466.htm

[5] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, The People’s Republic of China, “Acting on the Global Security Initiative To Safeguard World Peace and Tranquility,” May 6, 2022, https://www.mfa.gov.cn/eng/wjb/zzjg_663340/xws_665282/xgxw_665284/202205/t20220506_10682621.html

[6] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, The People’s Republic of China, “The Global Security Initiative Concept Paper,” February 21, 2023, https://www.mfa.gov.cn/mfa_eng/xw/wjbxw/202405/t20240530_11343274.html

[7] The State Council, The People’s Republic of China, “The Diversified Employment of China’s Armed Forces,” April 2013, https://english.www.gov.cn/archive/white_paper/2014/08/23/content_281474982986506.htm

[8] Ministry of National Defense of the People’s Republic of China, “China’s Military Strategy,” May 2015, http://eng.mod.gov.cn/xb/Publications/WhitePapers/4887928.html#:~:text=In%20the%20implementation%20of%20the,wars%2C%20deepen%20the%20reform%20of

[9] The State Council, The People’s Republic of China, “Full Text: China’s National Defense in the New Era,” July 2019, https://english.www.gov.cn/archive/whitepaper/201907/24/content_WS5d3941ddc6d08408f502283d.html

[10] Amrita Jash, “Xi’s Global Security Initiative: In Pursuit of China’s Own Interests and Ambitions,” ThinkChina, June 16, 2022, https://www.thinkchina.sg/politics/xis-global-security-initiative-pursuit-chinas-own-interests-and-ambitions

[11] “Full text: China’s Position on the Political Settlement of the Ukraine Crisis,” Xinhuanet, February 24, 2023, https://english.news.cn/20230224/f6bf935389394eb0988023481ab26af4/c.html

[12] “China’s Special Envoy for Ukraine to Handle Progress of Peace Talks — Chinese MFA,” TASS, April 27, 2023, https://tass.com/world/1610641

[13] Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Kingdom of Sweden, “Joint Trilateral Statement by the People’s Republic of China, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and the Islamic Republic of Iran,” March 10, 2023, http://se.china-embassy.gov.cn/eng/zgxw_0/202303/t20230311_11039241.htm

[14] The State Council, The People’s Republic of China, “Palestinian Factions Sign Beijing Declaration on Ending Division, Strengthening Palestinian National Unity,” July 24, 2024, https://english.www.gov.cn/news/202407/24/content_WS66a0a508c6d0868f4e8e96b1.html

[16] The State Council, The People’s Republic of China, “Full Text: Keynote Address by Chinese President Xi Jinping at Opening Ceremony of 2024 FOCAC Summit”

[17] The State Council, The People’s Republic of China, “Full Text: Keynote Address by Chinese President Xi Jinping at Opening Ceremony of 2024 FOCAC Summit”

[19] Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Federal Republic of Somalia, “Ambassador Fei Shengchao Publishes a Signed Article Titled “No One is Safe until Everyone is Safe——China’s View on Global Security Governance”,” August 10, 2022, http://so.china-embassy.gov.cn/eng/zfgx_1/202208/t20220810_10740081.htm

[20] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, The People’s Republic of China, “The Global Security Initiative Concept Paper”

[21] Jevans Nyabiage, “China’s Horn of Africa Envoy Tells Regional Peace Conference He is Ready to Mediate Disputes,” South China Morning Post, June 21, 2022, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3182442/chinas-horn-africa-envoy-tells-regional-peace-conference-he

[24] The State Council, The People’s Republic of China, “Full Text: China’s Armed Forces: 30 Years of UN Peacekeeping Operations,” September 18, 2020, https://english.www.gov.cn/archive/whitepaper/202009/18/content_WS5f6449a8c6d0f7257693c323.html

[26] The State Council, The People’s Republic of China, “Full Text: China’s Armed Forces”

[28] Oita Etyang and Simon Oswan Panyako, “China’s Footprint in Africa’s Peace and Security: The Contending Views,” The African Review: A Journal of African Politics, Development and International Affairs 47, no. 2 (2020): 340, DOI: 10.1163/1821889X-12340022

[29] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, The People’s Republic of China, “Forum on China-Africa Cooperation Beijing Action Plan (2025-2027),” September 5, 2024, https://www.mfa.gov.cn/eng/xw/zyxw/202409/t20240905_11485719.html

[31] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, The People’s Republic of China, “Jointly Acting on the Global Security Initiative and Building a Community with a Shared Future for Mankind that Enjoys Universal Security,” September 15, 2024, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/xw/wjbxw/202409/t20240915_11491406.html#:~:text=Under%20the%20guidance%20of%20the%20GSI%2C%20China%20has%20scaled%20up,process%20of%20conventional%20arms%20control.

[32] The State Council, The People’s Republic of China, “China, Africa Embrace Closer Economic, Trade Ties,” August 14, 2024, https://english.www.gov.cn/news/202408/14/content_WS66bca5aac6d0868f4e8e9e94.html

[33] Oyintarelado Moses, “10 Charts to Explain 22 Years of China-Africa Trade, Overseas Development Finance and Foreign Direct Investment,” Global Development Policy Center, April 2, 2024, https://www.bu.edu/gdp/2024/04/02/10-charts-to-explain-22-years-of-china-africa-trade-overseas-development-finance-and-foreign-direct-investment/

[35] Thomas P. Sheehy, “10 Things to Know about the U.S.-China Rivalry in Africa,” United States Institute of Peace, December 07, 2022, https://www.usip.org/publications/2022/12/10-things-know-about-us-china-rivalry-africa#:~:text=3.,largest%20lender%20to%20African%20countries.

[37] Shirley Ze Yu, “What is China’s Investment End Game in Africa?” Africa at LSE, November 4, 2022, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/africaatlse/2022/11/04/what-is-chinas-investment-end-game-in-africa/

[39] Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, “Full Text: Keynote speech by Chinese President Xi Jinping at Opening Ceremony of 8th FOCAC Ministerial Conference,” December 2, 2021, http://www.focac.org/eng/gdtp/202112/t20211202_10461080.htm

[40] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, The People’s Republic of China, “Forum on China-Africa Cooperation Beijing Action Plan (2025-2027)”

[45] Isaac Cardon, “China’s Ports in Africa,” (In)Roads and Outposts: Critical Infrastructure in China’s Africa Strategy, NBR Special Report no. 98, May 2022, https://www.nbr.org/publication/inroads-and-outposts-critical-infrastructure-in-chinas-africa-strategy-introduction/

[46] Jana de Kluiver, “Africa Has Much to Gain from a More Contained BRI,” Institute for Security Studies, July 24, 2024, https://issafrica.org/iss-today/africa-has-much-to-gain-from-a-more-contained-bri#:~:text=China’s%20Belt%20and%20Road%20Initiative,ports%2C%20railways%20and%20renewable%20energy.

[47] Etyang and Panyako, “China’s Footprint in Africa’s Peace and Security,” 339-342.