An American diplomat, now in Washington, remembers vividly the day in Beijing – many years after Mr Jimmy Carter had left the White House – when he asked a group of Chinese students if they knew anything about him.

“All their hands shot up,” he recalled. “And they said, ‘He recognised China’.”

While the stage had been set earlier for the historic event by two-term US President Richard Nixon and his Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, it was still certainly a fateful decision when, on Jan 1, 1979, Washington recognised the government in Beijing as China’s legitimate government.

Mr Carter was then in the middle of his 1977 to 1981 term as president of the United States.

Four months later, on April 10, 1979, the Taiwan Relations Act became law in Washington – and, without amendments, remains to this day the basis for the US’ relations with China and Taiwan.

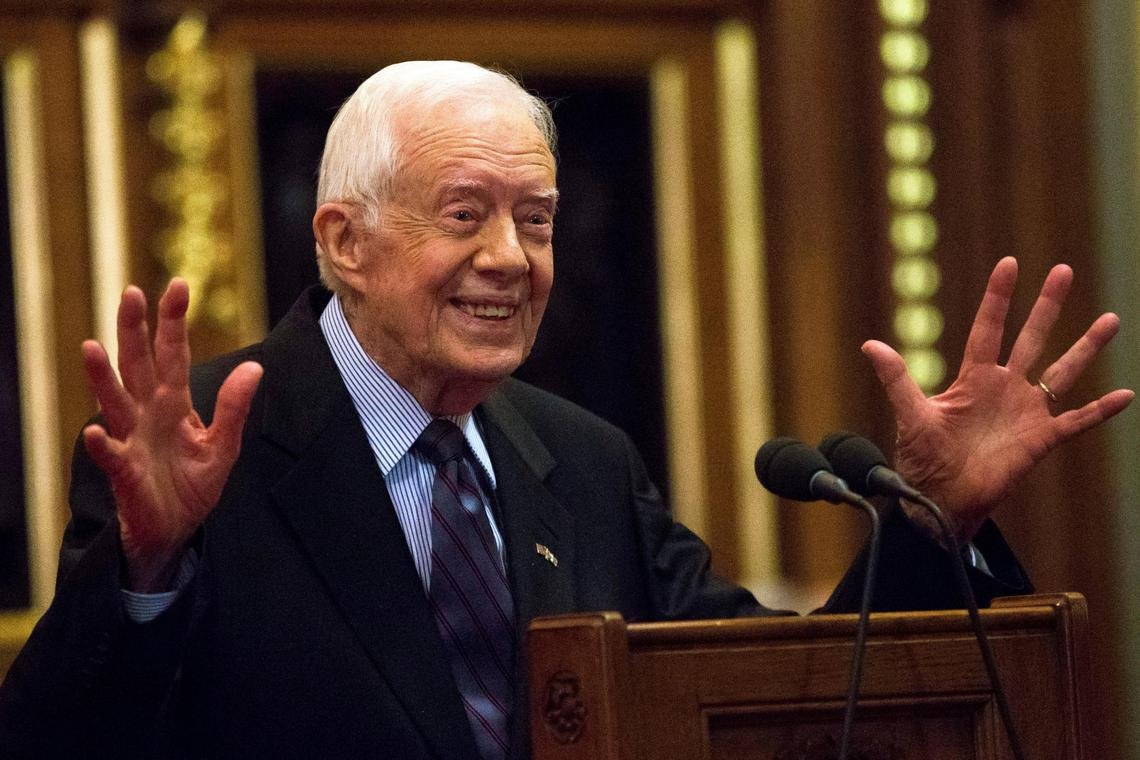

Former US president Jimmy Carter announcing new sanctions against Iran in retaliation for taking US hostages, at the White House, on April 7, 1980.PHOTO: REUTERS

The Act states that the US’ “decision to establish diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China rests upon the expectation that the future of Taiwan will be determined by peaceful means and that any effort to determine the future of Taiwan by other than peaceful means, including by boycotts or embargoes, is considered a threat to the peace and security of the Western Pacific area and of grave concern to the United States”.

It also states that the US “shall provide Taiwan with arms of a defensive character and shall maintain the capacity of the United States to resist any resort to force or other forms of coercion that would jeopardise the security, or social or economic system of the people of Taiwan”.

Mr Carter died at his home in Plains, Georgia, on Dec 29, at the age of 100.

The other far-reaching developments during his term in office were the end of detente with the Soviet Union’s 1979 invasion of Afghanistan, the Iranian revolution, and his reversal on withdrawing American troops from the Korean peninsula.

Hard-nosed realists considered Mr Carter somewhat naive.

American Pulitzer Prize-winning author and journalist Kai Bird, in his 2021 book The Outlier: The Unfinished Presidency Of Jimmy Carter, mentions that several years after Mr Carter had moved back to Plains, Georgia, Mrs Jehan Sadat, the widow of Egyptian Prime Minister Anwar Sadat who was assassinated in 1981 (and who shared the Nobel Peace Prize with Mr Carter and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin for the 1978 Camp David Accords), read him a note by her late husband.

(From left) Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, US President Jimmy Carter and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin during the signing of the Camp David Accords at the White House in Washington on Sept 17, 1978.PHOTO: REUTERS

In the note, Mr Sadat described Mr Carter as “the most honourable man I know”.

“Brilliant and deeply religious, he has all the marvellous attributes that made him inept in dealing with the scoundrels who run the world,” the note said.

Upon the note being read to him, Mr Carter apparently paused for a moment, then smiled and replied, “Well, maybe, but I’ll never change.”

Mr Carter had the instinct of a peacemaker and the vision of a human rights activist, but was drawn into and forced to confront the realities of the Cold War, said Dr Glenn Altschuler, professor of American Studies at Cornell University.

“Yes, he signed Salt II – the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty – with the Soviet Union. But he also had to, or felt he had to, respond to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, with what some now think was an overreaction, and some think sowed the seeds of what later became the horrors of both the… Taliban and of Osama bin Laden in Afghanistan.”

Under Mr Carter – and advised by National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski – the

Central Intelligence Agency and US allies delivered weapons to Afghan mujahideen fighting the Soviets.

US assistance had begun even earlier, in 1979, to opponents of the pro-Soviet regime in Kabul. In a January 1998 interview for French magazine Le Nouvel Observateur, Mr Brzezinski said it had the effect of drawing the Soviets into the “Afghan trap”. The Soviet Union became bogged down and suffered heavy losses from the well-armed Afghan mujahideen, and eventually withdrew in February 1989 – a defeat that contributed to the eventual collapse of the Soviet Union but also led to the Taliban seizing power in Kabul in 1996.

“What is most important to the history of the world? The Taliban or the collapse of the Soviet empire?” Mr Brzezinski argued.

Mr Carter was drawn into Cold War conflicts, Dr Altschuler said. “He was, I would say, a reluctant Cold Warrior, but a Cold Warrior nonetheless.”

The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan led Mr Carter to reverse his policy of detente with the Soviet Union.

Visitors watching a documentary about the life of former US president Jimmy Carter at the Jimmy Carter National Historical Park in Plains, Georgia, on Feb 19, 2023.PHOTO: REUTERS

A second about-face in Asia came when Mr Carter wanted to withdraw the 40,000 American troops deployed on the Korean peninsula – a promise he had made during his 1976 campaign for the White House.

He was persuaded against this, and to this day, over 20,000 US troops remain stationed in South Korea.

Mr Franz-Stefan Gady, senior fellow for Cyber Power and Future Conflict at the International Institute for Strategic Studies in Washington, wrote in a 2018 article in The Diplomat: “The majority of the US foreign policy establishment, especially the defence and intelligence communities – what today would be known as the deep state – as well as US Congress, in particular, members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and Armed Forces Committee, vehemently opposed the President’s withdrawal plans.

“Ultimately, the concerns of most opponents within the establishment boiled down to two major points: the state of US conventional deterrence in East Asia and the loss of US credibility as a reliable ally and partner.”

But if Mr Carter was dovish in the beginning, it was principally the invasion of Afghanistan that turned him around, said Dr Robert Manning, a distinguished senior fellow with the Reimagining US Grand Strategy project at the Stimson Centre in Washington.

“He started becoming much more hardline… and that carried over,” Dr Manning told The Straits Times. “Everybody talks about (Ronald) Reagan, but Carter started all this,” he said, referring to aid to the Afghan mujahideen, and positioning medium-range nuclear missiles in Europe aimed at the Soviet Union.

Former US president Jimmy Carter and his wife Rosalynn during a game between the Atlanta Braves and the Toronto Blue Jays at Turner Field in Atlanta, Georgia, on Sept 17, 2015.PHOTO: AFP

Mr Reagan succeeded Mr Carter in 1981 and is widely credited with having won the ideological-military struggle of the Cold War, with the fall in 1989 of the Berlin Wall, and the subsequent 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union.

It is also argued that the twin crises of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the Iran hostage crisis during Mr Carter’s term led to the US expanding its military reach via bases in the Indian Ocean region.

In 1980, Mr Carter outlined what became the “Carter doctrine”, stating that the US would use military force, if necessary, to defend its national interests in the Persian Gulf. It was a direct response to the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan.

The hostage crisis was triggered on Nov 4, 1979, when Iranian college students supporting the Iranian revolution that had deposed the US-backed Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi took over the American Embassy in Tehran, trapping 52 American diplomats and citizens (they were released on Jan 20, 1981 – Mr Carter’s last day in office.)

Diplomacy failed. Mr Carter ordered a military operation, which was mounted on April 4, 1980, and failed, killing seven American servicemen in a helicopter crash. The fiasco triggered the resignation of Secretary of State Cyrus Vance.

But it was also Mr Carter the humanitarian, idealist and peacemaker who made human rights a key feature – even the essence – of US foreign policy. It led him to raise concerns that Beijing’s one-child policy was a violation of human rights when he hosted China’s paramount leader Deng Xiaoping.

Mr Deng reportedly retorted: “How many (Chinese) people do you want (to have in the US)? Ten million? Twenty million?”

A shop with a banner in support of former US president Jimmy Carter in Plains, Georgia, on Feb 21, 2023.PHOTO: AFP

In a 2019 article in the Shanghai Institute of American Studies’ “40 People on 40 Years” series commemorating the 40th anniversary of diplomatic normalisation, Mr Carter is quoted as saying: “China and the US will always have differences of opinion, but we should reject the view that compromise, no matter how minor, is a sign of weakness.

“Instead, we should seek to accommodate differences to maintain the good relations Deng and I established 40 years ago.”

The focus on human rights continues as well to this day – and remains a source of some dissonance, as it was then.

Dr Manning said: “If you think back, our allies in Asia were authoritarian – Taiwan, South Korea, Indonesia.

“If you went around the region, there were not many democracies. So there was a tension in our policy, with this human rights imperative that was always more rhetorical than real, but… a source of some tension in terms of us trying to impose values.

“On the other hand, though the heavy lifting had been done before he got there, he finished the job of normalising with China.”

“Carter was more impactful than people give him credit for.”

Mr Carter’s humanitarian side became ascendant after he left office. Starting in September 1984, he and his wife Rosalynn became a feature around the world in their hands-on fieldwork for home-building charity Habitat for Humanity.

The former first lady preceded her husband of 77 years, dying on Nov 19, 2023, at the age of 96.

In a statement, the former president said: “Rosalynn was my equal partner in everything I ever accomplished.

“She gave me wise guidance and encouragement when I needed it. As long as Rosalynn was in the world, I always knew somebody loved and supported me.”

- Nirmal Ghosh was formerly US bureau chief at The Straits Times.

Join ST’s Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.