China will be watching Iran’s uranium enrichment programme closely in the coming months, hopeful that the country’s new reformist president, Masoud Pezeshkian, can slow his country’s march towards developing nuclear weapons.

Pezeshkian’s decisive victory over the preferred candidate of Iran’s religious and military establishment reflected widespread public support for his vow to diplomatically re-engage the West, analysts say.

A congratulatory message on July 7 from Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s top diplomatic adviser, Kamal Kharrazi, was interpreted as a green light for the president-elect to pursue a “tactical shift” in Tehran’s stance.

Kharrazi, a former foreign minister and chairman of Iran’s Strategic Council on Foreign Relations, said in a statement that Pezeshkian’s emphasis on using prominent foreign policy experts promises to solve “the problems caused by cruel Western sanctions” with “dignity and authority”.

However, to make meaningful progress on negotiating a diplomatic reset with the West and easing sanctions, analysts say Pezeshkian will need to offer concessions on Iran’s nuclear programme – such as slowing enrichment, allowing resumed international inspections, and de-escalating tensions with the United States. These steps, while not a major overhaul of policy, could help persuade European powers Britain, France and Germany to re-engage in talks about reviving a 2015 nuclear deal.

“They are basically tactical adjustments,” said Eric Brewer, a previous director for counterproliferation on the US National Security Council.

“Pezeshkian can help usher in nuclear diplomacy in a post-JCPOA world,” he wrote on the X platform, in reference to the 2015 deal known formally as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action that former US President Donald Trump torpedoed in 2018. “He’s positioned to help shift the conversation internally and, presumably, in a constructive direction.”

If that diplomatic path forward takes shape, it could pave the way for indirect dialogue with the US on loosening some of Washington’s unilateral sanctions that have crippled the Iranian economy.

Iran’s leadership structures may appear rigid on the surface, but the system allows for surprising amounts of flexibility, according to Josef Gregory Mahoney, a professor of politics and international relations at East China Normal University in Beijing.

Though Supreme Leader Khamenei “still has final say” on policymaking, the government can “swing to some extent between different positions, more or less conservative”, he said, giving it the ability “to change tactics and try new approaches, particularly when facing changing circumstances”.

Even if … all sanctions are dropped, Iran will still need strong relations with China

This fluid approach could benefit Iran’s relationship with China, which “prefers partnerships with countries that have stable relations with others, the West especially,” Mahoney said.

“China is not in a situation where it depends on Iran for anything, and it doesn’t want to be in a situation where Iran is desperate for support,” he told This Week In Asia, adding that Beijing believes “it’s better to have friends that are not regarded as pariahs or facing heavy sanctions”.

“Even if there’s a complete normalisation of ties and all sanctions are dropped, Iran will still need strong relations with China to advance its development goals,” Mahoney said.

However, the path to better Iran-West relations remains uncertain, hingeing on the outcome of November’s US presidential election. Trump withdrew from the Iran nuclear deal in 2018 and his Democratic successor Joe Biden declined to rejoin upon taking office in 2021.

Since then, quiet diplomacy through Oman has been the only backchannel for dialogue, as formal nuclear talks with European powers broke down in 2022.

In return for Tehran holding back from decisive steps toward producing nuclear weapons-grade uranium, the US has been somewhat less zealous in enforcing sanctions on Iran’s oil exports to China, India, and other Asian economies via intermediaries in Malaysia and the United Arab Emirates.

Diplomatic mediation by Oman and other Gulf states has also helped prevent the Gaza conflict from escalating into a wider regional war pitting Israel and its Western allies against Iran with its “Axis of Resistance” proxies in Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, and Yemen.

These efforts were facilitated by Iran’s moves to mend ties with its Arab neighbours under the country’s previous president, Ebrahim Raisi, who held office for three years before his death in a helicopter crash in May.

China’s remedial role

China has encouraged the regional detente, even brokering the March 2023 deal to restore diplomatic relations between Iran and the Gulf monarchies after a seven-year rupture.

However, Beijing’s diplomatic balancing act – and its escalating tensions with the US – has translated into little progress on implementing the comprehensive strategic partnership (CSP) agreement it reached with Iran in 2021.

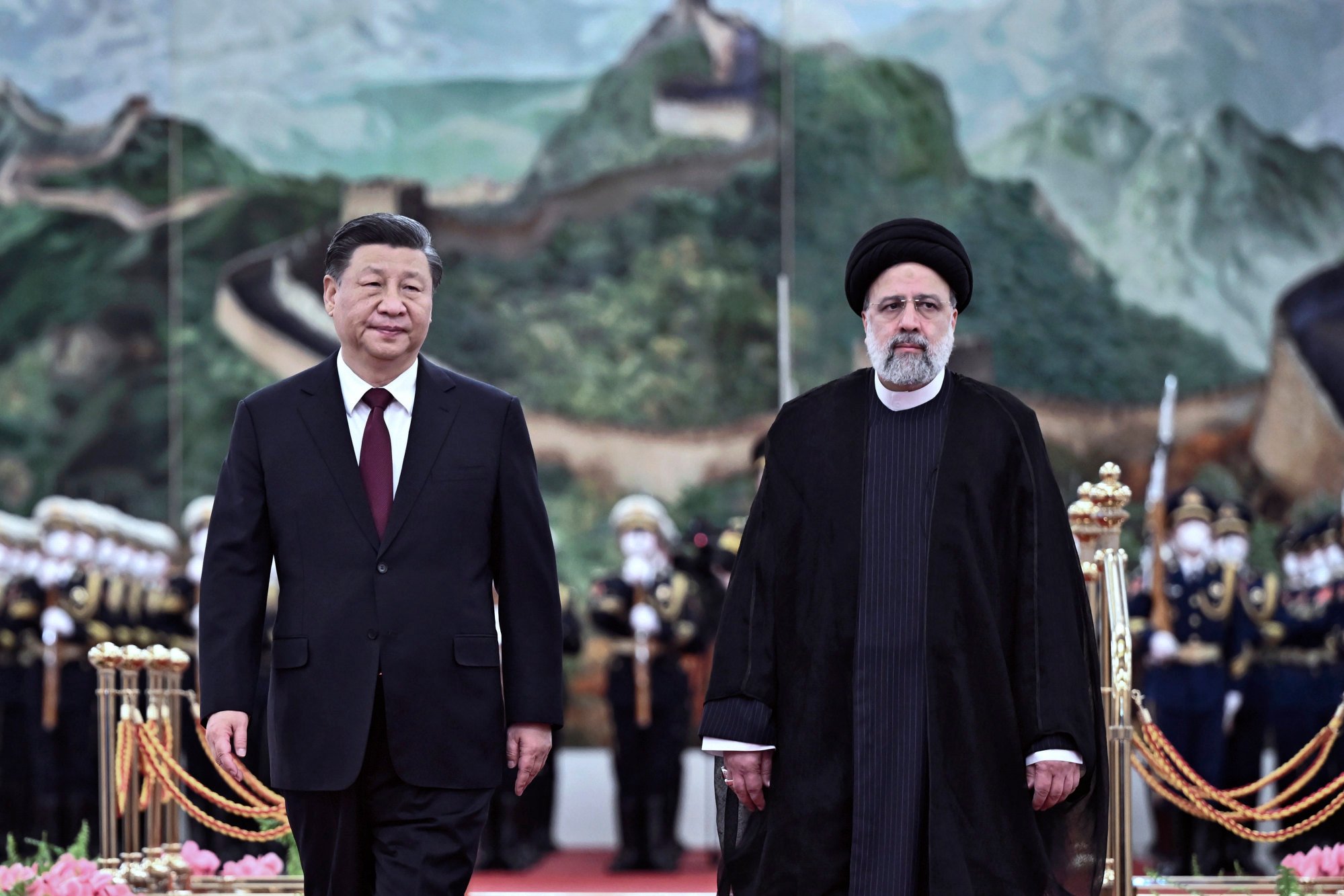

This lack of Chinese investment has frustrated Pezeshkian, who raised the issue during his election campaign. In response, Chinese President Xi Jinping pledged to “guide the deepening” of the CSP in his congratulatory message to Iran’s president-elect, signalling Beijing’s desire to strengthen ties despite the geopolitical complexities.

“China is aware that frustration within Iran on the CSP agreement has reached the top of the establishment, and there is the risk it’d boil over, given Pezeshkian’s political leanings and balanced views on international affairs”, said Ahmed Aboudouh, head of the China studies research unit at the Emirates Policy Centre in Abu Dhabi.

While Xi has sought to address this rhetorically, Aboudouh argues that “establishing comprehensive economic relations with Iran is a tall order that might contradict other, crucially important, Chinese interests.”

At the same time, Beijing “understands that Iran doesn’t have major alternative options in the short term”, he told This Week In Asia.

This dynamic could shift if Biden were to be re-elected and reinvigorate nuclear negotiations with Iran, according to Aboudouh, who is also an associate fellow with London-based think tank Chatham House. As a pre-emptive measure, Xi is “trying to say: ‘Look, we acknowledge our role in sustaining the shallowness of our partnership, but we will make it up for you.’”

Beijing views Iran through the lens of its broader objective to strike a “grand bargain to balance competing Asian power interests while denying Western powers access”, according to East China Normal University’s Mahoney

Iran’s regional influence makes it a valuable partner, but China may only consider “pumping more money” into the country if its relations with the West improve and if the US and Europe take similar steps, Aboudouh said.