Editor’s Note: Leonardo Jacopo Maria Mazzucco is a specialist on maritime operations in the Persian Gulf and nearby waters who also closely follows the defense industries of the GCC states.

By Barbara Slavin, Distinguished Fellow, Middle East Perspectives Project

In July, a Chinese warship reportedly fired a military‑grade laser at a German multi-sensor surveillance aircraft operating over the Red Sea as part of the European Union-led maritime security mission known as Operation Aspides. The incident, which forced the aircraft to withdraw for safety, sparked a sharp protest from Berlin and raised eyebrows among Western allies.

While Beijing downplayed the episode, this incident, coupled with growing Chinese defense cooperation with the Houthis and Iran, sent a clear message: China is no longer content to sit on the sidelines of Red Sea security.

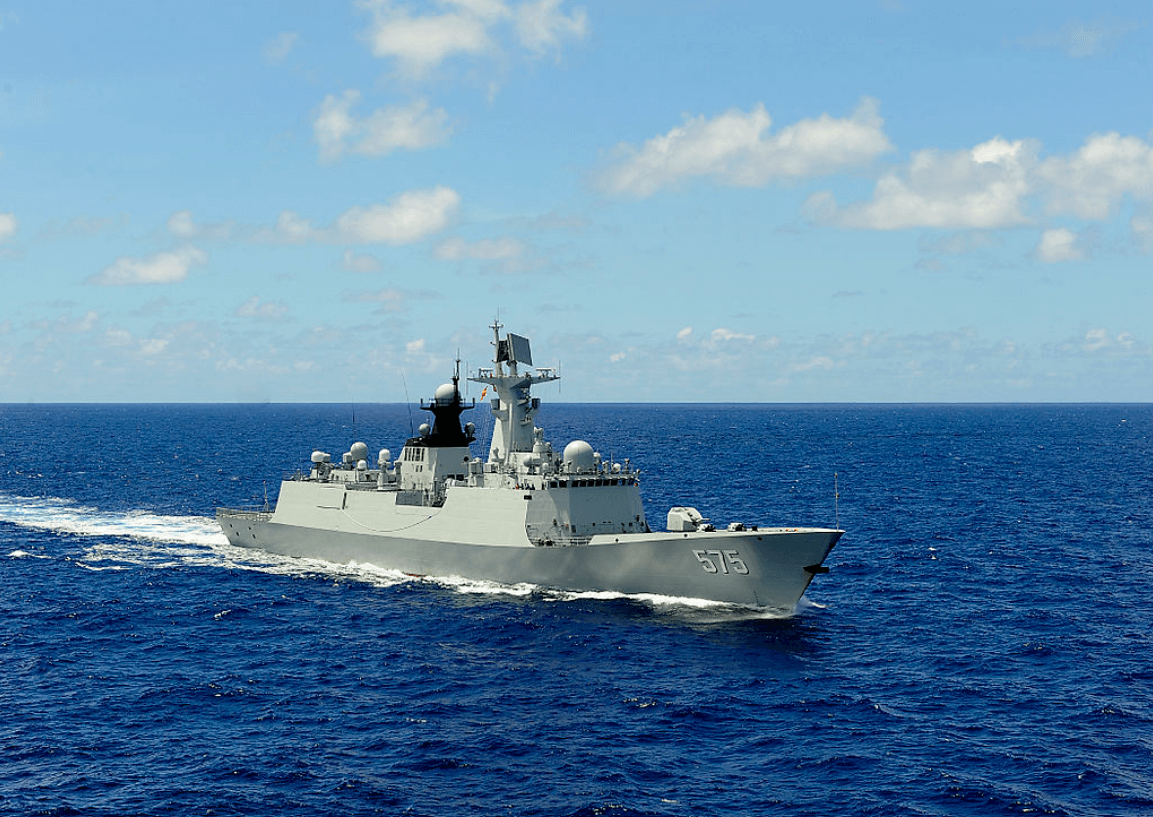

On July 2, 2025, a People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) frigate is believed to have directed a laser weapon at a German maritime patrol aircraft flying off the Yemeni coast. After the incident, the aircraft safely returned to the Djibouti-Ambouli airport, where it had been forward deployed since October 2024 to conduct intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance missions for Operation Aspides.

Notably, the targeted plane was not a platform of the German Armed Forces, but a contractor-operated aircraft manned by a civilian-military crew. While the extent of the damage to the plane and crew remains classified, German authorities confirmed the craft resumed routine patrol operations.

China rejected the accusations, denying using military-grade lasers to harass the German aircraft. This was not the first time Beijing had interfered with a Western aircraft’s operations in the Gulf of Aden, but the last incident was years ago. In 2018, the Pentagon condemned the repeated targeting of American C-130 aircraft at Camp Lemonnier, the U.S. military base in Djibouti.

This practice fits within the asymmetric warfare tactics of China’s armed forces, especially in contested zones. Beijing has a long track record of suspected military-grade laser incidents targeting U.S. and Australian patrol aircraft in Southeast Asia.

Directed-energy weapons range from low-power laser dazzlers that can temporarily blind optical systems or human eyes, to more powerful ship-mounted systems capable of disabling complex sensors and even destroying specific targets. With the German patrol aircraft resuming operations shortly after the incident, it is reasonable to conclude that the Chinese frigate employed a non-lethal laser system.

These emerging non-kinetic countermeasures have broad applications, and China leverages them for three main purposes: to deter adversaries, disrupt operations, and deny responsibility.

First, by using lasers, Beijing can signal displeasure at foreign surveillance flights without resorting to live fire or other overt coercive measures that could risk sparking a direct military confrontation. This approach enables China to challenge adversary operations in contested areas, while ensuring escalation control.

Second, high-powered lasers can disrupt reconnaissance missions by temporarily blinding optical sensors, cameras, and night-vision equipment aboard aircraft, while also posing health risks to crew members. By degrading surveillance capabilities without resorting to lethal force, Beijing gains a low-cost, effective countermeasure against foreign monitoring.

Finally, lasers grant plausible deniability. Laser incidents are hard to attribute with certainty because their beams are invisible, and their effects are generally temporary. This ambiguity makes lasers a potent gray-zone tool: disruptive enough to complicate Western operations but challenging to prove in diplomatic forums and to counter in the operational theater.

Support for the Houthis

On August 6, 2025, the Security Belt Forces, paramilitary units aligned with Yemen’s Southern Transitional Council, foiled an attempt to smuggle Chinese-made prefabricated cranes along a well-known smuggling route into Houthi-controlled territory. The cranes were most likely intended to replace logistics infrastructure damaged by Israeli airstrikes on Hodeidah, Yemen’s second-largest port and a vital lifeline for Houthis’ weapon stockpiles.

Three days earlier, the Counter-Terrorism Unit at Aden port intercepted a Houthi-bound shipment of lethal aid on a merchant vessel arriving from China. Redirected to Aden as operations at Hodeidah remained degraded, the cargo included equipment critical to establishing a drone manufacturing facility, such as power systems, guidance, and surveillance components, as well as assorted assembly parts.

A year earlier, in August 2024, the National Resistance Forces, a coalition led by General Tareq Saleh and operating under the authority of Yemen’s internationally recognized government, seized a dhow in the Red Sea carrying military aid bound for the Houthis. The haul included Chinese-made hydrogen gas cylinders and components intended to substitute traditional power sources for uncrewed systems, such as combustion engines or lithium batteries, with better-performing hydrogen fuel cells. The seizure underscored the Yemeni insurgent group’s intent to increase the sophistication of its arsenal by experimenting with advanced propulsion technologies.

Taken together, these interceptions point to two discernible patterns. First, with Hodeidah’s port still heavily damaged, the Houthis are increasingly seeking alternative smuggling corridors, even if this requires rerouting shipments through more heavily monitored entry points such as Aden. Second, while Iran remains the Yemeni armed group’s principal military sponsor, Chinese-sourced materiel is playing a growing role in sustaining its war effort and bolstering critical logistics infrastructure.

Evidence of Beijing’s direct involvement in the organized smuggling network supplying the Houthis with advanced weapon systems and critical components remains lacking. Yet, the accelerating pace of interceptions of China-manufactured and China-origin cargoes raises serious questions about whether state-affiliated firms are knowingly, or negligently, facilitating transfers of dual-use and military-grade items.

On September 11, the U.S. State Department sanctioned a group of individuals and entities, including several China-based companies that it accused of transporting military components to the Houthis.

The State Department’s April 2025 accusations against Chang Guang Satellite Technology, a commercial satellite firm with documented ties to the PLA, illustrate the same dynamic. Washington alleged that the company provided geospatial intelligence to support the Houthis’ anti-shipping campaign in the Red Sea. The company rejected the charges, but the timing and pattern add fuel to suspicions that China is quietly deepening its footprint in the conflict, even if indirectly.

The Chinese frigate suspected of carrying out the laser attack against the German patrol aircraft was most likely part of the PLAN’s 47th Naval Escort Task Force (NEFT), an independent maritime security initiative launched by Beijing in 2008 to counter Somali piracy. As the piracy threat receded in the mid-2010s, the task force evolved into China’s principal vehicle for maintaining a sustained naval presence in regional waters and advancing military cooperation with Iran.

Notably, warships from the 47th NEFT also participated in March 2025 in the Security Belt, the annual maritime counterterrorism and counter-piracy exercise jointly held by Iran, Russia, and China in the Gulf of Oman since 2019. That participation underscored how the PLAN task force has shifted from a narrowly defensive mission to serving as a platform for strategic alignment with Beijing’s key geopolitical partners, projecting influence well beyond its original mandate.

The prospect that Chinese surface combatants training alongside Iran and Russia could also engage in operational coordination with the Houthis is a worrisome development for regional and extra-regional actors alike. The concern is amplified by the possibility that more modern PLAN warships may join future NEFT rotations, including vessels potentially outfitted with advanced systems such as the LY-1 ship-mounted laser weapon unveiled during Beijing’s September 2025 military parade.

What’s Next

Taken together, the laser incident, the interdictions of Houthi-bound Chinese dual-use technology, and allegations of satellite-based intelligence support suggest a shift in China’s naval posturing. For years, Beijing was content to free ride on Western patrols that kept sea lanes open while monitoring U.S. and European naval movements through its maritime task force.

The outbreak of the Houthi anti-shipping campaign in November 2023 did not initially alter this approach. China read the Red Sea crisis primarily through an economic-security lens: prioritizing safe passage for its commercial fleet, reportedly via an Iranian-brokered agreement with the Houthis, and extending them indirect diplomatic cover.

Nearly two years on, however, Beijing appears to be testing more assertive tools to shape the battlefield itself, mixing plausible deniability with pragmatic empowerment of destabilizing armed groups. What once looked like symbolic signaling now risks becoming operational enablement of Houthi combat operations, raising the stakes for both regional and extra-regional actors.

Traditionally risk-averse and wary of uncontrolled escalation, China is still likely to tread carefully, balancing its interest in securing maritime shipping routes with the temptation to leverage gray-zone instruments that complicate attribution and erode Western naval presence.

Yet, for Beijing, this balancing act will be increasingly difficult to sustain. Mounting signs of growing Chinese support for the Houthis expose China to reputational costs among its Gulf commercial partners, undermine its claim to neutrality in regional conflicts, and heighten the risk that tactical gray-zone moves could trigger more complex diplomatic or military pushbacks.

Leonardo Jacopo Maria Mazzucco is an independent research analyst who focuses on the security and defense affairs of the Persian Gulf region. He is also an analyst at Gulf State Analytics, a Washington-based geopolitical risk consultancy. Leonardo tweets at @mazz_Leonardo..