It is an unsettled time on the African continent. For the first time since the post-Cold War 1990s, most of its regions are convulsed by conflict. All this unrest is occurring at a time of global disorder. Even before the U.S. electorate reinstalled President Donald Trump in the White House, a combination of factors, including economic headwinds stirred by Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and the COVID-19 pandemic as well as decaying multilateral institutions, were inhibiting collective action to contain security threats. Now the system is in even bigger trouble, as the new administration hints at deep cuts in assistance to organisations once central to peacemaking and toys with upending norms barring interstate land grabs. Sweeping U.S. foreign aid cuts announced in late January will immiserate millions, many in Africa. As AU heads of state gather for their annual summit on 15-16 February in this forbidding climate, they need to grapple with this reality: if the AU’s leaders and member states do not take greater responsibility for conflict prevention on the continent, it is quite possible that no one will. Africa’s peace and security challenges are a function of overlapping crises. On one side are the conflicts themselves. Start with the Horn of Africa, where civil war in Sudan threatens to fragment the state, spilling over into an extremely weak South Sudan and maybe into Chad as well. Somalia is in only a marginally better place, with yet another deadline having passed for phasing out the AU security mission that, in various iterations, has been helping Mogadishu battle Al-Shabaab insurgents since 2007. Ethiopia, traditionally the region’s anchor state, may be calmer than it was at the height of the Tigray conflict that wracked the country’s north from 2020 to 2022, but it is still fighting several insurgencies – including in the populous Oromia and Amhara regions. Looking west, in the central Sahel, transitional authorities have kicked out French and U.S. troops that helped provide security and intelligence support in the area and pulled out of the Economic Community of West African States. They are now looking to the Russian security firm called Africa Corps (formerly part of Wagner Group) for support in battling the jihadists who rampage across the region. These militants are still gaining ground, but the central Sahelian authorities portray the new arrangements as respecting their sovereignty in a way that France – the former colonial power – ostensibly did not. Toward the centre of the continent, Cameroon’s oft-overlooked Anglophone conflict enters its eighth year without a political resolution in sight, while fighting between Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) becomes more dangerous with each passing day: the former backs the March 23 (M23) rebels who captured Goma, the biggest city in the DRC’s North Kivu province, on 27 January. The rebels are seeking as well to take neighbouring South Kivu’s capital, Bukavu, although a unilateral ceasefire they announced on 4 February has paused their offensive for now. The risk this war could morph into a multi-country confrontation in the Great Lakes recalling the horrors of the 1990s is high. Finally, in southern Africa: post-election turmoil erupted in Mozambique in October after the opposition claimed the vote had been rigged. A harsh police reaction saw hundreds of protesters killed and the instability brought economic activity to a halt for months. The insurgency in the country’s northern Cabo Delgado province continues, albeit at a fairly low intensity.

If the crisis of conflict in Africa is reaching geographic proportions that it has not seen in decades, it is compounded by a further crisis of peacemaking.

[Moussa Faki Mahamat’s] most enduring legacy will likely be his chaotic management of the AU’s response to the Sudanese civil war.

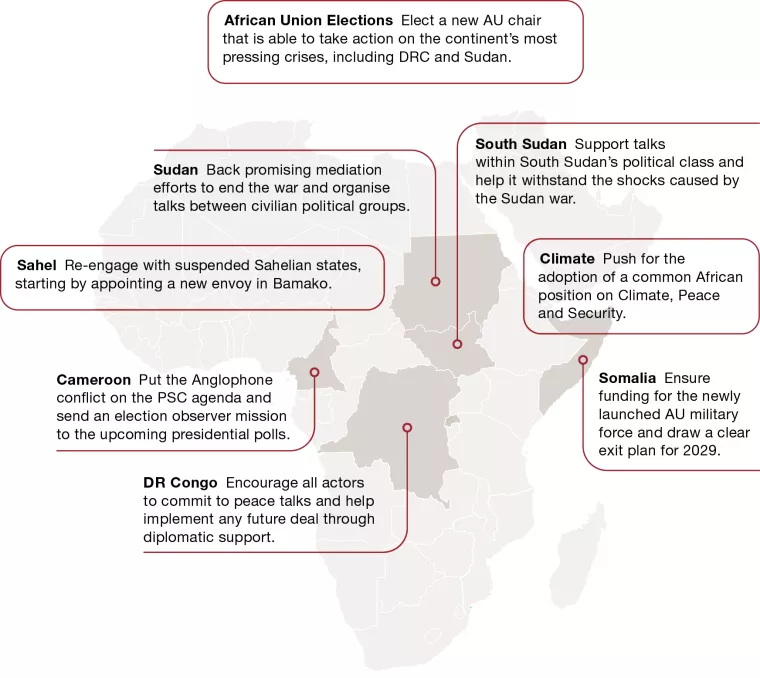

But Faki’s most enduring legacy will likely be his chaotic management of the AU’s response to the Sudanese civil war that broke out in April 2023. With the U.S. distracted by the conflict in Ukraine, and other outsiders (eg, the Arab Gulf powers) reportedly lining up behind one or the other of the two main sides in Sudan, strong African leadership was desperately needed. Yet when the Horn of Africa regional bloc the Intergovernmental Organisation for Development’s (IGAD) mediation effort ran aground, Faki was unable to raise the alarm about the severity of the crisis and muster an effective AU response.3 There are three candidates to replace Faki as chair. In line with a system of regional rotation adopted in March 2024, all three hail from eastern Africa.4 They are Kenya’s former prime minister, Raila Odinga; Djibouti’s foreign minister, Mahmoud Ali Youssouf; and the former finance minister of Madagascar, Richard Randriamandrato. Odinga and Youssouf are viewed as the front runners and have both mounted energetic campaigns. Odinga contends that he is best placed to bring the AU greater political clout, due to his high name recognition and Kenya’s stature as a major African power. He says he would be best able to get the ear of heads of state when attempting mediation. Youssouf offers a contrasting profile, with his supporters making the case he will add management capacity to a commission consistently criticised by member states as sclerotic and ineffective. He boasts considerable knowledge of AU institutions. Whoever prevails will have his work cut out for him. The obstacles to being an effective chair are many. Unlike the European Union, whose member states have handed certain powers to a supranational EU Commission, the AU is an intergovernmental organisation whose members have accorded it no measure of sovereignty. Real power lies with member states and, while enjoying prestige, the chairperson has little if any capacity to direct their actions. Still, an effective chair can draw upon the AU’s unique legitimacy among Africans to bring diplomatic focus to bear on the continent’s worst peace and security crises – a distinction for which the humanitarian catastrophe in Sudan and the potentially explosive conflict in the eastern DRC are now vying. Working to put out those fires should be the new chair’s top priority. Another key issue that the new chair will need to wrestle with relates to the organisation’s role in promoting good governance in accordance with the Lomé principles. At present, the AU has suspended Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Guinea, Gabon and Sudan after the military grabbed power in these countries. Typically, the AU lifts a suspension when an errant member state returns to constitutional rule after democratic elections. This approach appeared to work well in the early 2000s with a number of military regimes handing the reins back to civilians. But today the prospects of such reversals are far dimmer. In a new global age of impunity, it appears there is little chance any of the more recent coups, particularly those in the central Sahel, will be turned around anytime soon.5 Of the regimes in suspended countries, only the junta in Gabon has shown an interest in working to restore relations with the AU.

There is a growing realisation … that it is important to keep open lines of communication with military regimes.

The Sudanese state is on the brink of collapse. In April 2023, a dispute between the Sudanese army, led by General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), headed by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo “Hemedti”, over merging the latter into the former escalated into open warfare. Fighting broke out first in the capital Khartoum and rapidly spread across much of the country. With external backers helping sustain both belligerents – the United Arab Emirates is the RSF’s primary supporter, while Egypt is the army’s – the two sides feel they can gain more on the battlefield than at the peace table. Mediation efforts have therefore struggled. Although there are limits to what the AU can do to end the conflict, it could be doing more to call international attention to the crisis, press the warring parties into serious mediation and support discussions among Sudanese civilian groups about a political way forward. The costs of Sudan’s civil war are hard to exaggerate. It has created the world’s worst humanitarian crisis. Over 3.2 million people have fled to neighbouring countries such as Egypt, Chad, South Sudan and Ethiopia.7 An estimated 12 million Sudanese are displaced and 26 million face acute food shortages. The Trump administration’s confusing foreign aid cuts, though they include carveouts for life-saving humanitarian assistance, could leave even more Sudanese hungry.8 All the warring parties have subjected women and girls to sexual violence on a major scale. International actors have struggled to respond to the conflict. Efforts to convene face-to-face discussions between Burhan and Hemedti or their senior representatives have largely come to nothing. High-profile initiatives to date have included two rounds of talks in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, mediated by the kingdom and the U.S. (May and October 2023); discussions in Manama, Bahrain, organised by Egypt and the UAE (January 2024); and U.S.-led negotiations in Geneva (August 2024). In recent weeks, Türkiye has been trying to kickstart direct talks between the Sudanese army and the RSF’s Emirati backers, but it is too early to assess whether that effort will bear fruit.9 Behind this dismal record is a lack of motivation on both sides.10 Outside backers have propped up both the main belligerents, preventing either from dealing its foe a knockout punch and allowing both to keep fighting. The RSF, which had momentum for much of the conflict, controls most of the country’s western reaches and has recently moved into new areas in the south along the borders with South Sudan and Ethiopia. The army, which considers itself the country’s sovereign, is strongest in the north and east. In the last two months, the pendulum appears to have swung in its favour, starting with its capture (assisted, apparently, by Iran-supplied drones) of Wad Medani, an important city in Gezira state. On 24 January, the army then swept into Bahri, to Khartoum’s north, ending the RSF’s months-long siege of the army headquarters there. It was a major morale boost for the armed forces and a significant blow to the RSF, whose units withdrew without much of a fight, just as they had in Wad Medani. Still, even if the army manages to keep pushing the RSF out of the capital, the civil war looks set to rage on, especially in Darfur. Momentum could switch again.

Beyond each party’s sense that it can do better on the battlefield than at the peace table, there are other challenges to peacemaking efforts. The army will not speak to the RSF, which it calls a terrorist group, and rejects the inclusion of the UAE, which it (correctly) sees as the RSF’s prime enabler, at peace talks. Islamists associated with ousted authoritarian ruler Omar al-Bashir have joined forces with the army, seeking a return to power, alarming numerous African, Arab and Western governments as well as many Sudanese. Alliances that the army has struck with former rebel groups outside the country’s riverine centre complicate the picture. So, too, do questions about how to bring the views of civilian leaders and local communities into the frame. With both sides credibly reported to have committed atrocities, and both wishing to play a role in post-war governance, it is hard to imagine a settlement that will be embraced by the people who have suffered their abuses. In these difficult circumstances, the AU has understandably struggled to influence the course of events – though internal squabbling among officials over who should lead on the file has hardly helped. A roadmap for mediation and humanitarian assistance the AU drew up in May 2023 – right after the war began – was quickly rendered obsolete.11 A high-level panel formed in January 2024 has foundered so far because it lacks the political heft to compete with the other mediation initiatives.12 But the AU does have powers of moral suasion that it has been too reticent to use. While African leaders often ignore criticism from abroad, they are more hesitant to dismiss their peers. Megaphone diplomacy from the leadership of the AU – which still enjoys wide popular support across the continent – could have placed considerable pressure on the belligerents. The forthcoming election for a new AU Commission chair is an opportunity for a reset. The new chair could throw his full weight behind decrying the senseless bloodshed and urging the parties to come to the peace table. To create a bandwagon effect, he could call an extraordinary summit of AU heads of state to come up with new ways to actively encourage and support talks between the belligerents.13 The chair should also seek opportunities for AU participation in the most promising negotiation efforts of non-African powers. In parallel, the AU high-level panel, supported by the chair, should persist in trying to get Sudanese political and civil society actors around the table, in the hope that dialogue might create the scaffolding for a viable track to discuss options for a caretaker civilian administration once mediators achieve a ceasefire. Veteran AU diplomat Mohammed Ibn Chambas – who was appointed to lead the panel in January 2024 – should coordinate these efforts to supercharge the civilian track, perhaps working with Egypt, which made its own effort to bring civilian politicians together in July 2024. Given the tensions among various Sudanese civilian groups, it will be important for Chambas and his team to remain painstakingly neutral as they work to plant the seeds of a post-war Sudan.

Even before their sweep into Goma, the M23 and Rwandans had entrenched themselves in conquered parts of North Kivu.

The PSC has been careful not to take sides in the conflict [in the DRC], given the regional rifts.

The AU is a key source of support for the Somali government as it works to build up its security forces and battle the Al-Shabaab insurgency. The AU military mission, in place since 2007, was due to pull out in December 2024, but Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud asked that it stay. Mogadishu has not made sufficient progress in fighting Al-Shabaab to go it alone. A campaign in late 2022 that recovered territory in central Somalia fizzled before it could head to the south, where Al-Shabaab is strongest. It was hampered by political disputes, clan tensions and a Somali army that is still very much in development mode. The AU needs to find the funds needed for a revamped force, help the Somali government secure troop contributions and steer the country to the point where further AU missions are unnecessary. The newly minted AU Support and Stabilisation Mission to Somalia (AUSSOM) began operations in January. Its mandate is to support the Somali army in fighting Al-Shabaab, protect urban infrastructure, help enable humanitarian aid delivery and support state building.25 Despite its new name, AUSSOM is essentially a continuation of the previous African Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS) (2022-2024) and will step into the latter’s shoes over a six-month period. AUSSOM’s nearly 12,000 troops – close to half the peak strength of the original African Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) (2007-2022) – will be spread over about twenty bases in Somalia, down from approximately 80 in 2022. Most of these bases are near either strategic towns or important sites like airports. The guiding idea behind this reconfiguration is for the mission to hold critical nodes while freeing up Somali troops to go after Al-Shabaab. Still, the AU will also need to play a supporting role in Somali operations. Despite the substantial efforts of numerous foreign instructors, Somalia’s armed forces struggle to make battlefield gains without outside help. As the AU prepares to provide this support, it will need to work with Mogadishu to address key questions. The first is who will pay for the mission.26 In theory, part of the answer could lie in New York. In December 2024, the UN Security Council tentatively approved funding for AUSSOM through a new mechanism that allows the Council to cover up to 75 per cent of the costs of AU peace operations from UN assessed contributions.27 But the money will not flow until July and is conditioned on final Council approval, based on a vote to be taken in May.28 The previous U.S. administration abstained on the December resolution, taking the position that the new UN financing mechanism should be used for missions that are primarily offensive and time-limited in nature (AUSSOM fits neither bill). The new administration of President Donald Trump is almost sure to take an even more jaundiced view of an arrangement it can cast as costing U.S. taxpayers.29 The mission has also yet to find enough troops. The initial expectation was that the five ATMIS troop contributors – Burundi, Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda – would renew their commitments to minimise disruption. That plan came under strain when it seemed that a dispute between Somalia and Ethiopia (over the latter’s plans to secure a port in breakaway Somaliland) might keep Addis Ababa from sending soldiers. Turkish mediation has healed that rift, but there will still be changes: Burundi is set to depart the mission; Egypt is likely to provide a small number of specialist personnel; and specific troop commitments and important logistical arrangements are not yet nailed down.30

The AU, the Somali government and its partners will need to ensure that the mission does what the others failed to do by fully drawing down on time by 2029.

5. Searching for Ways to Engage the Central Sahel

While the AU has traditionally taken a back seat to ECOWAS … it took on several important roles at the outset of the security crisis in the Sahel.

While the AU has traditionally taken a back seat to ECOWAS when it comes to conflict resolution in West Africa, in line with the AU’s subsidiarity principle, which allocates primary responsibility to regional blocs, it took on several important roles at the outset of the security crisis in the Sahel. In 2013, the AU was instrumental in supporting elections that completed Mali’s transition back to civilian rule, after rapid jihadist advances the previous year had led to a coup d’état. In January 2013, it briefly deployed troops to the country before being replaced by a UN stabilisation mission, MINUSMA, with a large proportion of West African peacekeepers.36 But the organisation has not named an envoy for its only office in the central Sahel, MISAHEL in Bamako, since September 2023, illustrating the extent to which its influence in the region has diminished.37 But, as the central Sahel pulls away from ECOWAS politically and diplomatically, there may be more that the AU could usefully do to complement ECOWAS’ efforts. To be sure, relations between the AU and the central Sahelian administrations are strained, due to the fact the AU suspended all three countries following their respective coups. Nonetheless, the continental organisation, unlike ECOWAS, has largely refrained from messy public clashes with the AES’ authorities. The AU, for example, did not impose targeted economic sanctions or travel bans on the three, and it was reticent about supporting ECOWAS’ threats of a military intervention in Niger in 2023. Thus, there may still be room for the AU to play a diplomatic role in the Sahel. While the Lomé principles mean that the AU cannot lift suspensions on the AES members until they return to civilian rule, it could step up its engagement by staffing its Bamako office with a well-funded Sahel envoy, something Crisis Group has previously advocated. To have meaningful impact, the envoy should be a senior diplomat with sufficient international standing to meet regional heads of state. The envoy will also need to demonstrate a clear commitment to hearing out the AES countries’ concerns after a decade of limited contact with them.38 The organisation’s tone should be as neutral as possible, and its emphasis should be on maintaining regional integration – ie, on avoiding an end state that isolates the AES members from their neighbours and from continental structures to the detriment of their citizens and the entire region. The AU should also consider other ways in which to engage with countries in the central Sahel. The AU PSC took a decision in late 2023 to hold regular dialogues with countries suspended from the organisation, a formula that puts these states in a sort of “halfway house” where they can still discuss matters with African ambassadors in Addis Ababa, albeit on an informal basis.39 In June 2024, the PSC also, for the first time, held a meeting of its subcommittee on sanctions, dedicated to tracking the situation in countries suspended from the AU. The new subcommittee is tasked with investigating the causes of unconstitutional changes of government, monitoring the effect of sanctions on citizens and advising the AU about adapting its strategies.40 The organisation is right to stick with its stance against power grabs, but as the Sahel situation demonstrates, new tools for advancing that agenda could certainly be useful.41

Insecurity and logistical hurdles in [Cameroon’s] Anglophone regions and the Far North could … damage the vote’s credibility.

Against this backdrop, much of the country appears to be coming apart at the seams. The deteriorating economic picture, together with upheaval in the security sector and a growing sense of anarchy, have fuelled violence across the periphery. Recent months have seen inter-factional fighting, sometimes involving the state and other times not, in Upper Nile, Warrap, Jonglei, Unity, Central Equatoria and other states. Fury at the ill treatment of South Sudanese in Sudan’s civil war has been another trigger. In January, unrest shook Juba and locales across the country, as residents reacted to the purposeful killing of South Sudanese in Sudan.52 Authorities in Juba appeared to fear losing control, shutting down social media platforms.53 Many South Sudanese worry that local clashes could expand dramatically if political infighting continues and the economy flatlines. With a military that has not been paid in months – leaving soldiers to extort money from the public – Juba is hardly equipped to handle spreading unrest. Nor is it in a good place to create conditions for the political renewal that the country so desperately needs. In September 2024, the country’s leaders agreed to extend the 2018 peace agreement between the government and opposition groups and postpone by two years what would have been its first democratic elections. It was the right decision, given political divisions and the difficulty of staging credible polls amid widespread instability, but 2026 is not far off, and it will take major political and technical breakthroughs to keep the timetable on track. For elections to happen, South Sudan will need to compete a new constitution, conduct a census and register voters. Overhanging the preparations, moreover, are simmering questions about who might succeed Kiir, who has now ruled South Sudan for close to two decades but is known to be in poor health. Jockeying to be his replacement is in full swing and could set off its own power struggle within the regime. With South Sudan facing myriad challenges, there are several areas in which AU engagement could be of assistance. First, in order to shore up political stability in Juba, the AU should express its support of existing bilateral efforts by major member states. There is first the Kenya-led initiative to fortify the 2018 peace deal, which for all its imperfections provides the scaffolding for the country’s political order. Kenya launched that effort, dubbed the Tumaini initiative, in May 2024; it aims to forge a deal between the SPLM and holdout armed groups that did not sign the 2018 agreement.54 While the few opposition figures residing in Nairobi do not have substantial power themselves, the Kenyan-led talks appear to be the only serious forum at the moment for South Sudanese to discuss the way forward, and Kenya appears to be the only regional player active in trying to put together an accord among the Juba elites. The AU should publicly signal its support for the Kenya talks and encourage the government to conclude the process.

Cuts in U.S. humanitarian aid … will make it harder for African countries to cope with the aftermath of climate disasters.