Table of contents

- Executive summary

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Inducements in Chinese economic statecraft

- Chapter 3: Taiwan’s fight for diplomatic recognition

- Chapter 4: Targeted inducements in other areas of Chinese foreign policy

- Chapter 5: Conclusion and recommendations

Executive summary

As strategic competition between the United States and China intensifies, Washington and Beijing seek every possible advantage to gain an edge. In this environment, both countries are increasingly turning to economic statecraft—the use of economic coercion or inducement to pursue strategic goals—to advance their interests. Among these tools, economic coercion often garners the most attention, both as a preferred instrument of US policymakers and as a key driver of China’s expanding influence. However, this focus on coercion largely overlooks the strategic value of economic inducements, which serve as a powerful and affirmative means of cultivating influence. These positive measures enable the United States to leverage its economic strengths, advance its global interests, and support recipient countries—all while countering China with a more transparent, sustainable, and effective alternative.

For successive US administrations, the global reliance on US goods and services for economic growth has reinforced Washington’s ability and willingness to employ sanctions, trade restrictions, and unilateral economic measures to shape policy decisions in targeted countries. Meanwhile, decades of steady growth have enabled Beijing to wield its economic power in pursuit of strategic objectives. Considerable attention has been devoted to China’s use of economic influence and its deep integration into the global economy as tools of coercion, with Lithuania, Japan, and Australia among the most prominent targets of Beijing’s economic pressure campaigns. In response, nations worldwide have sought to resist China’s coercive tactics, implementing countermeasures both independently and in coordination with allies and partners.

China’s use of economic inducements, however, remains largely overlooked despite being instrumental in Beijing’s ability to encourage and entice countries into supporting its policies. Through public diplomacy, discourse power, strategic engagement with key constituencies, and coordination of economic activities among China-based entities, Beijing has demonstrated considerable skill in leveraging targeted incentives to persuade leaders—particularly in the Global South—that quid pro quo arrangements with China offer a viable path to economic development and growth. These leaders often view US-China competition as an opportunity to enhance economic outcomes while bolstering their domestic political legitimacy.

Nowhere are the successes of China’s economic inducements more evident than in the gradual erosion of Taiwan’s formal diplomatic relationships. In less than a decade, Beijing has convinced eleven of Taiwan’s former diplomatic partners to switch recognition to China. Many of these shifts were achieved through carefully tailored inducements designed to align political leaders with Beijing’s strategic objectives. Contrary to popular narratives, these inducements were not always overwhelming financial offers or corrupt dealings; rather, Beijing strategically cultivated political and sectoral interests to incentivize a diplomatic realignment. Similarly, China has employed targeted economic inducements to expand its influence in multilateral institutions, garner support for its global initiatives, and secure market access for Chinese firms, among other strategic objectives.

Beijing’s use of economic inducements is particularly effective because China has tailored its measures to align with the specific needs of recipient countries and their leaders or political parties. For politicians in both democracies and authoritarian states, public promises of economic support from Beijing can boost domestic political support and international legitimacy. Even when Chinese projects are later exposed as inefficient or detrimental, their speed, cost efficiency, and willingness to assume risk continue to make them appealing.

Too often, Chinese firms and state-run lenders are perceived as the most viable—or only—option available to Global South countries seeking economic development. Yet the appeal of Western economic engagement remains strong, and Washington should look beyond unilateral coercive measures to offer an affirmative vision of economic development and compelling alternatives to Chinese projects and financing.

Transparency and sustainability are key strengths of US and Western economic initiatives. Collaborating with like-minded allies and partners can enhance the financial viability and long-term success of development projects. The US International Development Finance Corporation warrants greater attention as a critical instrument of US economic statecraft, while US public diplomacy institutions play a vital role in countering Chinese influence and promoting Western-led initiatives. By leveraging targeted inducements, multilateral economic initiatives, and strategic partnerships with like-minded countries, the United States can expand its economic statecraft tool, diminish the appeal of Chinese economic engagement, and advance its interests abroad.

Chapter 1: Introduction

Economic statecraft and US-China competition

The foundation of strategic competition between the United States and China is an unprecedented level of economic interdependence—both with each other and with the global economy. This interdependence, largely sustained by post-World War II institutions, has driven global economic growth for decades. However, it now also enables the more deliberate use of economic ties to pursue strategic and geopolitical objectives.1Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman, “Weaponized Interdependence: How global economic networks shape coercion,” International Security 44, no. 1 (2019): 42–79, https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00351.

Economic statecraft—the use of economic means to pursue political goals—is deployed through two primary levers: coercion and inducement. Of the two, economic coercion has received far more attention in academic literature, policy analysis, and China-specific scholarship. Beijing’s use of economic inducements—both promised and delivered—is less appreciated and relatively unexplored, as is how the United States can employ similar measures to advance its national interests.2On inducements in international relations, see Han Dorussen, “Mixing Carrots with Sticks: Evaluating the Effectiveness of Positive Incentives,” Journal of Peace Research 38, no. 2 (March 2001): 252, https://www.jstor.org/stable/425499; Richard Haass and Meghan L. O’Sullivan, eds., Honey and Vinegar: Incentives, Sanctions, and Foreign Policy (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2000); Miroslav Nincic, “Getting What You Want: Positive Inducements in International Relations,” International Security 35, no. 1 (July 2010): 138–183, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40784650.

These economic inducements can take a variety of forms: official international assistance or humanitarian aid (such as grants, capacity building, technical assistance, or budget support), development finance (such as loans, credit, guarantees, and public-private partnerships), investment, and access to currency, trade, preferential tariffs, and subsidies are some of the most cited.3Nicole Goldin and Mrugank Bhusari, “II. Positive economic statecraft: Wielding hard outcomes with soft money,” in Kimberly Donovan et al., Transatlantic Economic Statecraft: Different Approaches, Shared Risk, Atlantic Council, September 20, 2023, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/us-eu-uk-need-shared-approach-to-economic-statecraft/#path-forward. Studies have investigated these mechanisms of influence, including the use of inducements to garner votes in the United Nations and the World Bank.4Ilyana Kuziemko and Eric Werker, “How Much Is a Seat on the Security Council Worth? Foreign Aid and Bribery at the United Nations,” Journal of Political Economy 114, no. 5 (October 2006), https://doi.org/10.1086/507155; Christopher Kilby, “The political economy of conditionality: An empirical analysis of World Bank loan disbursements,” Journal of Development Economics 89, no. 1 (May 2009): 51–61, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2008.06.014. Corruption through bribes and kickbacks, political donations, academic donations, and other incentives to buy elite support for the sender’s goals are also forms of inducement.5Audrye Wong, “Peddling or Persuading: China’s Economic Statecraft in Australia,” Journal of East Asian Studies 21, no. 2 (2021): 283–304, https://doi.org/10.1017/jea.2021.19. Promises—free trade agreements (FTAs), memoranda of understanding (MOUs), market access promises, and signing ceremonies for new economic arrangements—can be a potent incentive, even if the final product is substandard or not completed.

The existing literature divides these inducements into two broad categories: quid pro quo arrangements that involve conditionality and unconditional structural engagement.6Wong, “Peddling or Persuading;” Nincic, “Getting What You Want;” Michael Mastanduno, “Economic Statecraft, Interdependence, and National Security: Agendas for Research” in Power and the Purse: Economic Statecraft, Interdependence, and National Security, eds. Jean-Marc F. Blanchard, Edward D. Mansfield, and Norrin M. Ripsman (London: Frank Cass, 2000). This latter category of inducements creates a commercial motivation to favor the provider of the incentive, in turn building and expanding interest groups in the target country that support closer economic relations with the sending state.7Albert O. Hirschman, National Power and the Structure of Foreign Trade (University of California Press, 1945). In reciprocal arrangements—the focus of this study—the provider of the inducement explicitly links the incentive to the desired policy behavior in the recipient country, requiring a clear request (whether in public or private) that can be accepted or denied. While it is important to separate the intent of these two categories of economic inducement, they are also intertwined: broad structural factors can act independently while simultaneously shaping the frameworks for quid pro quo arrangements. Promises of structural engagement—such as pledges to increase trade, investment, or aid in agreements or MOUs—can serve as transactional inducements. However, insufficient follow-through often impedes the sustained alignment of interests and behavior.

Weaponizing US economic statecraft

For decades, US foreign economic policy has often sought to wield the centrality of the US economy and financial system as a weapon to compel desired behavior. Sanctions have been used by the United States across a wide range of issues and are policy tools that can quickly earn broad domestic political support—for both good and ill.8Daniel W. Drezner, “The United States of Sanctions: The Use and Abuse of Economic Coercion,” Foreign Affairs 100, no. 5 (September/October 2021): 142–154. Their efficacy has long been debated in academic literature, with concrete answers hampered by the evolving nature of sanctions, the difficulties in defining sanctions, economic coercion, and success, as well as the empirical challenges of identifying the full universe of cases.9Robert A. Pape, “Why Economic Sanctions Do Not Work,” International Security 22, no. 2 (Autumn 1997): 90–136, https://doi.org/10.2307/2539368; Adam Taylor, “13 times that economic sanctions really worked,” Washington Post, April 28, 2014, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2014/04/28/13-times-that-economic-sanctions-really-worked/. More recently, export controls and trade tariffs have come to the forefront as preferred instruments of US economic statecraft, with China as a primary target. These punitive measures seek to blunt the impact of Beijing’s industrial policies and its efforts to bolster its domestic economy at the expense of the United States and other countries.

Concerns about the overuse of economic sanctions and other punitive measures have grown in policy discourse as the unintended consequences of sanctions and potential harms to US foreign policy interests become more apparent.10Jeff Stein and Federica Cocco, “The Money War: How Four U.S. Presidents Unleashed Economic Warfare Across the Globe,” Washington Post, July 25, 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/interactive/2024/us-sanction-countries-work/. In a 2016 speech, then–Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew warned of the risks of sanctions overreach: “[W]e must be strategic and judicious in how we apply sanctions” to avoid driving business activity away from the US financial system.11US Department of the Treasury, “Speech Preview: Excerpts of Secretary Lew’s Remarks on Sanctions at The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace,” press release, March 30, 2016, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jl0397. Daleep Singh, a former deputy national security advisor for international economics, wrote that “the United States and its partners will need to apply the same creativity and urgency toward developing a positive vision for economic statecraft as they have in designing sanctions and other restrictive measures in the recent past.”12Daleep Singh, “Forging a positive vision of economic statecraft,” New Atlanticist, Atlantic Council, February 22, 2024, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/forging-a-positive-vision-of-economic-statecraft/.

Goldin and Bhusari, “II. Positive economic statecraft,” 22–23.

This is not to say that inducements have not been used at all; the United States has effectively employed such measures before. As detailed in a report from the Atlantic Council’s Geoeconomics Center, there are numerous examples of the United States and the European Union (EU) using “positive economic statecraft” in a variety of contexts. In tactical cases, the United States and the EU linked the provision of aid, finance, or trade to a specific desired outcome or action.13Goldin and Bhusari, “II. Positive economic statecraft,” 22–23. For example, the United States has conditioned nonmilitary aid to Pakistan on cooperation with counterterrorism efforts; the EU offered Moldova a support package after it joined the EU’s sanctions against Russia in 2023; and a Tax Information and Exchange Agreement between the United States and Panama in 2011 was a prerequisite to a subsequent FTA. The Pakistan and Panama cases indicate that US policymakers have already used economic inducements to great effect and should consider employing them more extensively moving forward.

In other cases, the failure of inducements to entice desired policy changes in North Korea and Iran has perhaps contributed to a decline in their use.14Stephan Haggard and Marcus Noland, Hard Target: Sanctions, Inducements, and the Case of North Korea, (Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press, 2017); Richard Nephew, “The Hard Part: The Art of Sanctions Relief,” Washington Quarterly 41, no. 2 (2018): 63–77, https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2018.1484225. US economic statecraft was used in attempts to convince Pyongyang and Tehran to abandon the pursuit of nuclear weapons. It is also notable that Chinese economic statecraft toward North Korea has been of questionable influence. China and Russia, likewise, are competitors of the United States for whom the benefits of positive incentives are difficult to envision—except perhaps on extremely specific and discrete issues. Convincing these regimes to accede to US policy demands, however, is a high-stakes outlier in policy—significant enough that failure in this area should not dissuade US policymakers from employing inducements more broadly in foreign policy. There remain opportunities to use positive incentives to advance both US interests and development needs in many countries.

The US focus on sanctions-based economic statecraft has contributed to Washington’s underappreciation of the needs of developing countries. It is difficult to present an affirmative offer to these countries when the United States is so focused on discouraging undesired behavior—most often through threats and sanctions. This has created openings for Chinese inducements, which can significantly influence the policies and behaviors of leaders in countries requiring economic growth and development. Moreover, developing countries’ real or perceived lack of competitive alternatives from Washington and its allies has significant foreign policy and national security implications for the United States. It has been easy to dismiss the geopolitical importance of these small and developing countries. However, in times of great power competition, their role is amplified—they are needed for international support, to combat transnational threats, and as markets for US companies. For example, the Solomon Islands previously received scant attention from the United States, but Beijing’s expanding influence there has raised concerns throughout the Indo-Pacific region that China seeks naval basing rights. Washington’s response to the China-Solomon Islands security agreement signed in April 2022 included warnings about China’s intentions and a belated flurry of diplomatic activity.15Michael E. Miller and Frances Vinall, “China signs security deal with Solomon Islands, alarming neighbors,” Washington Post, April 20, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/04/20/solomon-islands-china-security-agreement/; Kate Lyons and Dorothy Wickham, “The deal that shocked the world: inside the China-Solomons security pact,” Guardian, April 20, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/apr/20/the-deal-that-shocked-the-world-inside-the-china-solomons-security-pact. In the decades following the Cold War, the United States was, by default, the most important partner for many countries due to its economic influence and global security interests. However, with China now a near-peer economic competitor, Washington needs to expand its toolkit.

Scope of the study

To the extent possible, this report seeks to establish a clear and direct linkage between China’s strategic intent, the promise and provision of economic inducements, and a discrete outcome—either acquiescence or refusal of Beijing’s demands. Ideally, a specific policy request from China is apparent, as is whether the target country complied. In the absence of such evidence, close process tracing—through interviews, contemporaneous research and reporting, MOUs, and contracts—can help reveal the contours of influence attempts. The potential use of inducements to influence a recipient country to withhold action it might otherwise take makes process tracing particularly valuable, while expert interviews can help uncover such hidden cases. This report benefited from off-the-record interviews in Washington and Taipei with US and Taiwanese officials, academics, journalists, and representatives of several of Taiwan’s current diplomatic partners.

Establishing intent is a fundamental and inextricable challenge in any study of power and influence—a task made even more difficult by China’s opaque state-capitalist system. By focusing on national-level policies in the target country that are of strategic importance to Beijing, this research seeks to circumvent some of these challenges by explicitly analyzing areas where intent is unquestioned. This approach enables a more focused assessment of the factors—both in China’s offer and in the target country—that contribute to success. While this method inherently introduces selection bias, the observational nature of this study, China’s strategic use of diverse tools of economic statecraft, and the immediate policymaking implications of these findings necessitate a targeted analysis.

The focus of this report will be on the effects of publicly announced inducements, though attempts at bribery or elite capture through private rents can also play an important role in China’s economic statecraft strategy. There are pragmatic reasons for the decision to deemphasize corruption—namely, the methodological challenges of identifying under-the-table deals. However, the intent behind dark money is often unrelated to a specific public policy issue or is merely a feature of, rather than the driving force behind, larger announced deals. Publicly announcing these agreements allows the recipient leader or regime to leverage the deal with China to bolster political legitimacy both domestically and internationally. Still, by identifying issue areas where China has strategic intent and process-tracing the events surrounding success (or failure), this report aims to assess the impact and deployment of various inducements, including bribes and corruption.

Chapter 2: Inducements in Chinese economic statecraft

Economic inducements have played an important role in China’s foreign policy strategy for decades, harking back to Mao Zedong’s foreign aid to Africa.16Mingjiang Li, “Front Matter” in China’s Economic Statecraft: Co-optation, Cooperation, and Coercion, ed. Mingjiang Li (World Scientific Series on Contemporary China Volume 39, 2017). In recent decades, China’s rapid economic development has led Beijing to use inducements to create an international environment more aligned with its interests.17Christina Lu, “China’s Checkbook Diplomacy Has Bounced,” Foreign Policy, February 21, 2023, https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/02/21/china-debt-diplomacy-belt-and-road-initiative-economy-infrastructure-development/. Without an extensive array of security relationships, Beijing has been largely dependent on economic arrangements to extend its influence and pursue desired policy change in other countries.18Bethany Allen, Beijing Rules: How China Weaponized Its Economy to Confront the World (New York, NY: Harper, August 1, 2023). Since Xi Jinping took power, China has used this strategy more frequently and with greater success, commensurate with the growth of its economy and its increasing importance to global markets.19Vida Macikenaite, “China’s economic statecraft: the use of economic power in an interdependent world,” Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies 9, no. 2 (2020): 108–126, https://doi.org/10.1080/24761028.2020.1848381.

For good reason, international attention focuses primarily on the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) as a potential—and powerful—conduit for Chinese economic influence. Chinese institutions have poured many billions of dollars into BRI projects and the initiative’s constituent parts, from the original Maritime Silk Road and Silk Road Economic Belt to the Digital Silk Road, Polar Silk Road, and Health Silk Road. Beijing claims that more than 150 countries and institutions have signed on to the BRI, and China has introduced the Global Development Initiative (GDI) alongside the BRI to promote economic development in the Global South.20Christoph Nedopil, “Countries of the Belt and Road Initiative,” Green Finance and Development Center, Fudan University, 2025, https://greenfdc.org/countries-of-the-belt-and-road-initiative-bri/. In recent years, Xi has also launched a slew of complementary initiatives to expand China’s influence, including the Global Security Initiative (GSI), Global Civilization Initiative, and Global Artificial Intelligence Initiative.21Michael Schuman, Jonathan Fulton, and Tuvia Gering, How Beijing’s newest global initiatives seek to remake the world order, Atlantic Council, June 21, 2023, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/issue-brief/how-beijings-newest-global-initiatives-seek-to-remake-the-world-order/.

The extensive literature on China’s global economic footprint notes that BRI-associated projects are a ubiquitous aspect of Beijing’s growing influence.22For just a few examples, see Jennifer Hillman and David Sacks, China’s Belt and Road: Implications for the United States, Independent Task Force Report No. 79, Council on Foreign Relations, updated March 2021, https://www.cfr.org/task-force-report/chinas-belt-and-road-implications-for-the-united-states/findings; Cheng-Chwee Kuik, Irresistible Inducement? Assessing China’s Belt and Road Initiative in Southeast Asia, Council on Foreign Relations, June 15, 2021, https://www.cfr.org/sites/default/files/pdf/kuik_irresistible-inducement-assessing-bri-in-southeast-asia_june-2021.pdf; Jean-Marc F. Blanchard, “Problematic Prognostications about China’s Maritime Silk Road Initiative (MSRI): Lessons from Africa and the Middle East,” Journal of Contemporary China 29, no. 122 (2020): 159–174, https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2019.1637565. These studies provide valuable insight into Chinese trade, investment, and/or financing in a specific country, within a wider region, or emanating from a single large-scale initiative such as the BRI. Many of these works use broadly applicable indicators to highlight China’s structural engagement and its resulting influence, and these indicators serve as important context for Beijing’s ability to shape the policies of target states. A 2021 RAND Corporation report emphasizes trade and foreign direct investment as the economic inputs of China’s influence while also highlighting the complexity of the literature on the relationship between influence and economic ties.23Michael J. Mazarr et al., Understanding Influence in the Strategic Competition with China, RAND Corporation, June 30, 2021, 25–34, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA290-1.html. A 2023 RAND Corporation report compares US and Chinese approaches to development highlighting how China blends different forms of economic engagement into its larger portfolio of development cooperation.24Eric Robinson et al., Development as a Tool of Economic Statecraft, RAND Corporation, October 23, 2023, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA2271-1.html. Large databases such as the American Enterprise Institute’s China Global Investment Tracker and AidData offer valuable insights into China’s overseas investment and construction, as well as its development financing.25“China Global Investment Tracker,” American Enterprise Institute, accessed July 23, 2023, https://www.aei.org/china-global-investment-tracker/; “Chinese Development Finance Program,” AidData, accessed July 23, 2023, https://www.aiddata.org/cdfp. These are just a few notable works in this space.

Yet membership in the BRI—most often through the signing of an MOU—is not the only channel for Chinese economic engagement, and not all of this engagement, BRI or otherwise, confers immediate or quid pro quo benefits for Beijing. China’s domestic overcapacity, for example, is often cited as an important driver of Chinese firms’ overseas activities, suggesting that not every investment or trade deal is meant to extend Beijing’s geopolitical influence.26Zenobia T. Chan finds that China’s dual goals behind the BRI—addressing domestic economic problems and gaining international acceptance for its governance models—undermine each other and make quid pro quo arrangements difficult. If the sender (China) lacks an incentive to rescind an inducement, the target has no incentive to concede to the sender’s demand, as the target expects to receive the inducement regardless of its actions. Zenobia T. Chan, “Affluence without Influence: The Inducement Dilemma in Economic Statecraft,” SSRN, April 9, 2024, http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4789560. To some degree, the BRI can be viewed as a political slogan, mobilizing domestic and international actors toward the initiative’s broader goals without directing specific actions.27Jinghan Zeng, Slogan Politics: Understanding Chinese Foreign Policy Concepts (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020). The purpose of this report is to highlight this distinction—between non-conditional economic engagement and targeted quid pro quo inducements—as fundamental to the US response to China’s economic statecraft.

China has tied the promise and delivery of specific economic inducements to achieving discrete strategic goals. These quid pro quo arrangements can be obscured in a larger review of China’s economic inputs. In Greece, China’s footprint has grown rapidly following a privatization push after the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. However, as noted in an International Republican Institute report, “Beijing’s influence over government discourse and decision-making in Athens is disproportionate to its level of investment and economic importance in absolute terms.”28David Shullman, ed., A World Safe for the Party: China’s Authoritarian Influence and the Democratic Response, International Republican Institute, 2021, 55, https://www.iri.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/final_bridge-ii_execsummary.pdf. Growing trade and investment relations, such as in Greece’s energy sector, serve as the backdrop and conduit for Beijing’s influence, but China’s investment in the port of Piraeus—and the promised economic growth associated with the investment—was the proximate cause of political decisions by Greece in favor of Beijing in the EU.29Briana Boland et al., CCP Inc. in Greece: State Grid and China’s Role in the Greek Energy Sector, Center for Strategic and International Studies, October 19, 2022, https://www.csis.org/analysis/ccp-inc-greece-state-grid-and-chinas-role-greek-energy-sector.

Economic inducements, however, are not universally positive for leaders in recipient countries, and China’s infrastructure investments and development projects have rightly received significant attention for their negative externalities. There is an extensive list of projects that have failed to deliver on their promises or have triggered opposition from local communities due to environmental, social, and governance (ESG) concerns, debt distress and difficulty refinancing loans, cost and timeline overruns, imported labor from China, corruption, and other issues.30For examples of related analyses, see Ryan Dube and Gabriele Steinhauser, “China’s Global Mega-Projects Are Falling Apart,” Wall Street Journal, January 20, 2023, https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-global-mega-projects-infrastructure-falling-apart-11674166180; John Hurley, Scott Morris, and Gailyn Portelance, “Examining the Debt Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative from a Policy Perspective,” Center for Global Development, March 4, 2018, https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/examining-debt-implications-belt-and-road-initiative-policy-perspective.pdf; Elaine K. Dezenski, “Below the Belt and Road: Corruption and Illicit Dealings in China’s Global Infrastructure,” Foundation for Defense of Democracies, May 2020, https://www.fdd.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/fdd-monograph-below-the-belt-and-road.pdf. These externalities constitute the core of Western warnings to the Global South of Chinese economic influence.

While many countries are now more cautious about accepting Chinese bids—and Beijing has pulled back on some lending in the past few years—in many cases, Chinese projects are either the only option to meet development and infrastructure needs or the most competitive option for emerging economies. Fifth generation (5G) cellular networks, high-speed rail, and port infrastructure are some prominent examples.31Hillman and Sacks, China’s Belt and Road. Indeed, Chinese projects can offer ready-made links between state-owned companies and state-owned policy banks, allowing for a streamlined bidding process (or to avoid competitive bidding altogether) and rapid project development.32Rafiq Dossani, Jennifer Bouey, and Keren Zhu, “Demystifying the Belt and Road Initiative,” RAND Corporation, Working Paper 1338, May 2020, https://www.rand.org/pubs/working_papers/WR1338.html.

These projects’ connections to the Chinese party-state are a leading concern for US and Western policymakers. China’s state capitalist system allows the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to orchestrate the economic activity of state-run financial institutions, state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and even private corporate entities in a way that the United States and its partners have not matched.33Barry Naughton and Briana Boland, CCP Inc.: The Reshaping of China’s State Capitalist System, Center for Strategic and International Studies, January 31, 2023, https://www.csis.org/analysis/ccp-inc-reshaping-chinas-state-capitalist-system; James Reilly, Orchestration: China’s Economic Statecraft Across Asia and Europe (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2021). At the same time, US researchers and policymakers should not assume that China is uniformly intent or effective in its use of economic ties to achieve strategic goals, nor that Chinese corporate entities are eager participants in these endeavors.34William J. Norris, Chinese Economic Statecraft: Commercial Actors, Grand Strategy, and State Control (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2016). Beijing can encourage economic activity abroad for several possibly overlapping reasons, including strategic gain, national economic strength, and support for Chinese companies abroad.35Scott L. Kastner and Margaret M. Pearson, “Exploring the Parameters of China’s Economic Influence,” Studies in Comparative International Development 56 (2021): 20–24, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-021-09318-9. Likewise, it is important to interrogate the mechanisms through which Beijing hopes to gain strategically from its economic reach and growth. Outside of coercion and inducements, economic statecraft initiatives can enhance political influence by creating vested interests, transforming public and elite opinion, and giving rise to structural power.36Ibid., 24–30.

Even as China faces an economic slowdown, there is little reason to believe that Xi will deemphasize economic statecraft in his foreign policy.37Peter S. Goodman, “China’s Stalling Economy Puts the World on Notice,” New York Times, August 11, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/11/business/china-economy-trade-deflation.html; Gerard DiPoppo, “Focus on the New Economy, Not the Old: Why China’s Economic Slowdown Understates Gains,” RAND Corporation, February 18, 2025, https://www.rand.org/pubs/commentary/2025/02/focus-on-the-new-economy-not-the-old-why-chinas-economic.html. He is acutely aware that domestic perceptions of foreign policy issues, particularly those related to territorial disputes and political legitimacy, are paramount to the political survival of the CCP. Independent of ongoing struggles in the domestic economy, Beijing has learned from past failures and is reining in some of its more ostentatious projects, shifting toward “smaller” and “greener” programs.38Carla Freeman and Henry Tugendhat, “Why China is Rebooting the Belt and Road Initiative,” United States Institute of Peace, October 26, 2023, https://www.usip.org/publications/2023/10/why-china-rebooting-belt-and-road-initiative. No longer able to spread economic largesse as widely, China may instead direct its capital toward economically or strategically advantageous projects, fostering more sustainable and targeted engagement.39Matt Schrader and J. Michael Cole, “China Hasn’t Given Up on the Belt and Road,” Foreign Affairs, February 7, 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/china-hasnt-given-belt-and-road; Matthew Mingey and Agatha Kratz, “China’s Belt and Road: Down but not Out,” Rhodium Group, January 4, 2021, https://rhg.com/research/bri-down-out/.

Existing research on Chinese economic statecraft and implications for the study of inducements

While the literature on Chinese economic statecraft and coercion is well established, relatively few works specifically examine Beijing’s use of inducements. Scholars of Chinese economic statecraft, however, have produced a robust body of research on Beijing’s use of coercion; these studies, while not focused on inducements, have important implications for the study of positive economic incentives. Recent think tank analyses—including from the Center for Strategic and International Studies, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, and Mercator Institute for China Studies—offer a snapshot of this research.40Matthew Reynolds and Matthew P. Goodman, Deny, Deflect, Deter: Countering China’s Economic Coercion, Center for Strategic and International Studies, March 21, 2023, https://www.csis.org/analysis/deny-deflect-deter-countering-chinas-economic-coercion; Fergus Hunter et al. “Countering China’s coercive diplomacy,” Policy Brief Report No. 68/2023, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, https://www.aspi.org.au/report/countering-chinas-coercive-diplomacy; Fergus Hanson, Emilia Currey, and Tracy Beattie, “The Chinese Communist Party’s coercive diplomacy,” Policy Brief Report No. 36/2020, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, https://www.aspi.org.au/report/chinese-communist-partys-coercive-diplomacy; Aya Adachi, Alexander Brown, and Max J. Zenglein, “Fasten Your Seatbelts: How to manage China’s economic coercion,” MERICS China Monitor, August 25, 2022, https://merics.org/en/report/fasten-your-seatbelts-how-manage-chinas-economic-coercion. Beyond those noted, also see Peter Harrell, Elizabeth Rosenberg, and Edoardo Saravalle, China’s Use of Coercive Economic Measures, Center for a New American Security, June 11, 2018, https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/chinas-use-of-coercive-economic-measures; Luke Patey, “The myths and realities of China’s economic coercion: Understanding Beijing’s evolving statecraft,” Danish Institute for International Studies, November 24, 2021, https://research.diis.dk/en/publications/the-myths-and-realities-of-chinas-economic-coercion-understanding. Together, these reports and others reveal important trends in China’s use of economic coercion that can be applied to the examination of strategic inducements.

First, the targets of Chinese coercive attempts are somewhat predictable, which likely holds true for inducements as well. These studies note that targets are largely Western-oriented, democratic, and developed. However, what remains unaccounted for is how China exerts influence in the Global South, where Beijing has consistently used positive economic incentives. Second, coercive measures are aimed at strategic industries with a strong political lobby in the target country; similarly, China carefully selects the recipients of economic inducements, targeting leaders, other political elites, and their constituents. Lastly, there are certain issues around which Beijing is likely to exert economic coercive force, including national sovereignty, national security, political legitimacy, and territorial disputes. To gain a full understanding of Beijing’s economic statecraft, it is also important to identify the issues which invite China’s economic inducements.

While there remains a dearth of research explicitly discussing China’s use of economic inducements as part of its larger economic agenda, investigations in this area have been increasing in recent years. This scholarship largely focuses on China’s non-conditional economic engagement or employs broad measures to identify correlations between specific Chinese incentives and policy outcomes. Evelyn Goh, for example, discusses economic inducements as a “preference multiplier” in China’s influence efforts in Southeast Asia, serving to politically advantage actors whose interests align with those of Beijing in a form of non-conditional structural engagement.41Evelyn Goh, “The Modes of China’s Influence: Cases from Southeast Asia,” Asian Survey 54, no. 5 (October 2014): 825–848, https://doi.org/10.1525/as.2014.54.5.825. In Africa, Ana Christina Alves argues that China’s development financing for infrastructure projects has had moderate success in achieving tactical and structural goals since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949.42Ana Christina Alves, “Chapter 9: China’s Economic Statecraft in Africa: The Resilience of Development Financing from Mao to Xi” in Mingjiang Li, ed., China’s Economic Statecraft. Dreher et al. argue for a need to differentiate types of Chinese aid to assess their effects on policy in Africa, concluding that China’s Official Development Assistance—though less so commercial loans—is driven by foreign policy considerations.43Axel Dreher et al., “Apples and Dragon Fruits: The Determinants of Aid and Other Forms of State Financing from China to Africa,” International Studies Quarterly 62, no. 1 (March 2018): 182–194, https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqx052. The authors measured foreign policy considerations through United Nations General Assembly votes and adherence to the “One China” policy—two common but flawed measures of policy alignment with Beijing. Several studies examine the limited effectiveness of China’s positive economic efforts to influence Taiwanese elections through strategic agricultural purchases. While these works offer valuable insights, they largely overlook quid pro quo arrangements in favor of statistical correlations.44Stan Hok-wui Wong and Nicole Wu, “Can Beijing Buy Taiwan? An empirical assessment of Beijing’s agricultural trade concessions to Taiwan,” Journal of Contemporary China 25, no. 99 (2016): 353–371, https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2015.1104868; Chi-hung Wei, “China’s Economic Offensive and Taiwan’s Defensive Measures: Cross-Strait Fruit Trade, 2005-2008,” China Quarterly 215 (September 2013): 641–662, https://doi.org/10.1017/S030574101300101X.

Audrye Wong provides an in-depth analysis of the issue, examining when Chinese inducements effectively achieve geopolitical goals.45Audrye Wong, “China’s economic statecraft under Xi Jinping,” Brookings Institution, January 22, 2019, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/chinas-economic-statecraft-under-xi-jinping/; Audrye Wong, “Reaping What You Sow: Subversive Carrots, Public Accountability, and the Effectiveness of Economic Statecraft,” Working Paper, 2020; Wong, “Peddling or Persuading.” She distinguishes between subversive carrots—which circumvent political processes and institutions in target countries—and legitimate seduction, arguing that countries with high-accountability domestic political institutions are less susceptible to subversive carrots. Because of this dynamic, she contends that China has been less successful in achieving influence than commonly assumed. The utility of this framework is clear. However, the intent behind these subversive carrots—often, but not always, involving hidden bribes and corruption—is not explicit, making its application difficult. These subversive carrots are not necessarily directed by the party-state, especially with other economic incentives at play. Even when they are, assessing the desired strategic outcome remains challenging—whether the engagement is non-conditional (such as increasing the market share of a Chinese SOE) or transactional.

This question of intent is one reason to deemphasize—though not discount—the potential effect of subversive carrots. Chinese inducements, particularly those related to the BRI and its infrastructure projects, are undoubtedly crafted to align with the needs and domestic political priorities of elites and decision makers in the target country. This, in turn, creates opportunities for graft, opaque deals, and a lack of accountability.46Jonathan E. Hillman, “Corruption Flows Along China’s Belt and Road,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, January 18, 2019, https://www.csis.org/analysis/corruption-flows-along-chinas-belt-and-road; Elaine K. Dezenski, “China Is Bailing Out Its Bad Best, and Handing the West a Geopolitical Opening,” Barron’s, May 18, 2023, https://www.barrons.com/articles/china-belt-and-road-loans-bailout-infrastructure-africa-asia-7f905df0. However, the assumption that these inducements are primarily intended to advance “strategic corruption”—the explicit use of bribes and elite capture to achieve geopolitical aims—lacks broad support, despite some important high-profile cases.47Philip Zelikow et al., “The Rise of Strategic Corruption,” Foreign Affairs 99, no. 4 (July/August 2020): 107–120, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/rise-strategic-corruption-weaponize-graft. In this report, the Solomon Islands and Kiribati are the two most apparent examples of possible corruption, though in both cases there are significant public benefits as well. Most significantly, such corruption is often linked to a Chinese company with a clear economic rationale for the project in question. Chinese inducements can be and have been used to secure lucrative business deals, facilitate personal enrichment for high-level policymakers and commercial actors on all sides, and to expand China’s non-conditional economic engagement. However, there is minimal evidence that these efforts are part of a larger scheme directed by the party-state to exert influence over specific strategic issues.

Explaining the success of Chinese inducements

For leaders and regimes in power, receiving economic inducements can enhance citizen perceptions of a regime’s performance, help secure public compliance, and strengthen both domestic authority as well as external validation of the regime’s position.48Johannes Gerschewski, “The three pillars of stability: legitimation, repression, and co-optation in autocratic regimes,” Democratization 20, no. 1 (January 2013), https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2013.738860. To reap these benefits, leaders in both authoritarian and democratic governments are eager to announce inbound investments, foreign aid, or trade agreements—even if they obscure the longer-term ESG trade-offs, or instances of bribery and corruption, associated with these deals.49Dreher et al., for example, found that Chinese aid is funneled to political leaders’ birth regions. Axel Dreher et al., “African leaders and the geography of China’s foreign assistance,” Journal of Development Economics 140 (September 2019): 44–71, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2019.04.003. Together, these factors increase the likelihood that the recipient of the inducement—most often the ruling regime—will achieve political stability and maintain its grip on power.

Broadly, China’s economic inducement strategy has been effective because it is sensitive to the domestic political needs of leaders and regimes in recipient states. Beijing promotes itself both as a member and leader of the developing world, free from the colonial and Cold War baggage associated with the United States and other Western institutions. China’s professed adherence to a nonaligned posture further facilitates a persistent diplomatic presence in the Global South and ensures a sympathetic ear for Chinese proposals.50“China wants to be the leader of the global south,” Economist, September 21, 2023, https://www.economist.com/china/2023/09/21/china-wants-to-be-the-leader-of-the-global-south. Moreover, China’s state-owned banks and firms are willing to finance and/or build what recipient countries want, rather than promoting projects that align with a predetermined set of values or development priorities. They also engage with state actors that Western institutions have neglected for various reasons. BRI projects address infrastructure and connectivity needs in developing countries; foreign aid provides a domestic political boost to elites in recipient countries; and promises of increased trade and investment make for good publicity, even when such pledges fail to materialize. These inducements allow for a sustained Chinese presence in a country that can build goodwill and help maintain stable relations.51Dossani, Bouey, and Zhu, “Demystifying the Belt and Road Initiative,” 25. While they often advance China’s broader non-conditional engagement objectives, they can also be tailored to meet specific needs.

The Lowy Institute’s Global Diplomacy Index offers a snapshot of China’s efforts in this regard. Beijing holds a slight lead over the United States in overall diplomatic posts (274 versus 271), embassies (173 versus 168), and consulates general (ninety-one versus eighty-three).52Ryan Neelam and Jack Sato, 2024 Key Findings Report, Lowy Institute Global Diplomacy Index, 2024, https://globaldiplomacyindex.lowyinstitute.org/key_findings. China has more posts in Africa, East Asia, the Pacific Islands, and Central Asia and is tied with the United States in the Middle East and South America. Reporting suggests that Chinese diplomats can be more adept at engaging with locals than the “wolf-warrior diplomacy” narrative of recent years would suggest.53Nahal Toosi, “‘Frustrated and powerless’: In fight with China for global influence, diplomacy is America’s biggest weakness,” Politico, October 23, 2022, https://www.politico.com/news/2022/10/23/china-diplomacy-panama-00062828; Duan Xiaolin and Liu Yitong, “The Rise and Fall of China’s Wolf Warrior Diplomacy,” The Diplomat, September 22, 2023, https://thediplomat.com/2023/09/the-rise-and-fall-of-chinas-wolf-warrior-diplomacy/. Beijing has emphasized discourse power as an important aspect of China’s influence abroad and seeks to “tell China’s story well.”54Jian Xu and Qian Gong, “‘Telling China’s Story Well’ as propaganda campaign slogan: International, domestic and the pandemic,” Media, Culture & Society 46, no. 5 (2024), https://doi.org/10.1177/01634437241237942. As detailed by researchers at the Atlantic Council and elsewhere, this discourse power manifests in various forms, including partnerships with local media, ostentatious branding of Chinese projects, the establishment of Confucius Institutes, training centers, province-led international communication centers, and other programs that promote China-affiliated ideas.55Niva Yau, A Global South with Chinese Characteristics, Atlantic Council, June 13, 2024, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/a-global-south-with-chinese-characteristics/; Alex Colville, “Telling Zhejiang’s Story,” China Media Project, December 4, 2024, https://chinamediaproject.org/2024/12/04/telling-zhejiangs-story/.

These various connections—diplomatic, commercial, informational, and educational—provide Chinese actors with access to local institutions and leaders, as well as insight into development priorities in recipient countries. The definition of “local” in this context varies widely depending on government structure, leadership dynamics, accountability mechanisms, and public opinion. In some countries, central leaders are the primary decision makers, while in others, municipal policymakers, businesspeople, or community leaders hold greater influence. Regardless of the political structure, China has established mechanisms to assess development needs and identify potential synergies. Beijing has also demonstrated an ability to identify important areas of economic development for targeted countries and take action—whether through vanity projects for leaders or investments in export markets with political significance.

In BRI projects in Southeast Asia, for example, power-holder diplomacy (currying favor with top leaders) and aligning the BRI with a host country’s national strategy or a leader’s vision are two key approaches to generating demand for inducements.56Kuik, Irresistible Inducement? These strategies highlight crucial aspects of how Beijing has pursued success in its economic statecraft. China has effectively communicated its vision for economic development—including through the BRI, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, and other lending institutions—to sympathetic and financially constrained countries. It has also identified critical needs, determined the most effective targets for inducements within domestic political environments, and assessed how these needs align with elite interests in recipient countries. In the Philippines, for example, Beijing actively supported the presidential candidacy of Rodrigo Duterte, who sought a break from the United States and actively courted BRI projects. Once elected, promises from China buttressed Duterte’s “Build, Build, Build” economic development campaign, including infrastructure projects focused on the then president’s home island of Mindanao.57Aileen S. P. Baviera and Aries A. Arugay, “The Philippines’ Shifting Engagement with China’s Belt and Road Initiative: The Politics of Duterte’s Legitimation,” Asian Perspective 45, no. 2 (Spring 2021): 277–300, https://doi.org/10.1353/apr.2021.0001.

These aspects of China’s economic statecraft—communication, identification, and assessment—are meaningless without the ability (or a credible promise) to deliver inducements in ways unmatched by Western countries or institutions. In some cases, this is a straightforward process. For example, Cambodia and Prime Minister Hun Sen received foreign aid in exchange for stifling opposition to China’s interests in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the region’s primary multilateral grouping. Similarly, as part of the Solomon Islands’ diplomatic switch to China in 2019, Beijing replaced a Taiwanese fund with its own and constructed a grant-funded sports stadium. Meanwhile, Beijing’s unfulfilled promises to Italy enticed Rome—frustrated with Europe’s lack of economic support—to join the BRI.58David Sacks, “Why Is Italy Withdrawing From China’s Belt and Road Initiative?” Asia Unbound, Council on Foreign Relations, August 3, 2023, https://www.cfr.org/blog/why-italy-withdrawing-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative.

Many countries in the Global South require infrastructure and connectivity investment, an area where China’s project development model is often welcomed. In the Xi era, these projects fall under the BRI umbrella, though their core characteristics predate the initiative. As identified in a Council on Foreign Relations Independent Task Force Report on the BRI, these characteristics include state backing and access to cheap credit for Chinese companies, state-owned commercial and policy banks directed by Beijing to embrace BRI projects, a lack of concessionary terms (at least in the contract) that make loans more accessible, and an eagerness to launch projects quickly—often to minimize financial viability assessments or ESG transaction costs.59Hillman and Sacks, China’s Belt and Road. Together, these factors enable Chinese projects to move swiftly from planning to construction, with a high tolerance for risk.

Need for further study

Important work has been done to better understand China’s economic statecraft, including valuable scholarship on China’s non-conditional economic engagement and its resulting influence. Yet little attention has been given to how China uses targeted economic incentives to address the immediate development and economic needs of recipient states and, through these measures, alters their policy behavior to align with Beijing’s geopolitical goals.

Since 2016, eleven nations have recognized Beijing, leaving Taiwan with only twelve remaining diplomatic partners. Perhaps most notably, Beijing has successfully enticed several of Taiwan’s diplomatic partners to switch recognition to China by offering public economic incentives that Taiwan and its Western partners choose not to match.60Thomas J. Shattuck, “The Race to Zero?: China’s Poaching of Taiwan’s Diplomatic Allies,” Orbis 64, no. 2 (2020): 334–352, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orbis.2020.02.003. The president of Paraguay, which continues to recognize Taiwan, made this dynamic explicit when he requested $1 billion in investment from Taipei to help resist Chinese pressure.61Helen Davidson, “Paraguay asks Taiwan to invest $1bn to remain allies,” Guardian, September 29, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/sep/29/paraguay-asks-taiwan-to-invest-1bn-to-remain-allies-china. Inducements are an ideal mechanism for enticing Taiwan’s partners to switch, as they align with Beijing’s self-professed support for developing countries and are less likely than coercion to provoke domestic resistance in the recipient country. Taiwan’s diplomatic partners are all small, developing nations, where a relatively small amount of inducements can have a significant impact. There is little doubt that Beijing will continue to use inducements to erode Taiwan’s remaining diplomatic relationships and will press its advantage unless countered by a deliberate effort.

Beijing has also successfully used inducements to gain influence in multilateral fora and shape proceedings in its favor. In Southeast Asia, China is often, and rightly, criticized for its belligerent tactics in the South China Sea; at the same time, it has managed to forestall a strong regional response through the targeted use of inducements to key players in ASEAN, the region’s consensus-based organization.62Luke Hunt, “Analysts: Cambodia to ‘Pay Price’ for Siding with China,” Voice of America, July 29, 2016, https://www.voanews.com/a/analysts-cambodia-to-pay-a-price-for-siding-with-china/3439768.html; Renato Cruz De Castro, “Explaining the Duterte Administration’s Appeasement Policy on China: The Power of Fear,” Asian Affairs: An American Review 45, no. 3/4 (October-December 2018): 165–191, https://doi.org/10.1080/00927678.2019.1589664. Both Cambodia and the Philippines, for example, have moderated their criticism of China or supported its positions based on promised and delivered inducements.63Cambodia offers an interesting case, as Prime Minister Hun Sen is portrayed as Beijing’s lackey, yet he still secured new offers of public economic assistance in 2012 and 2016 in exchange for supporting China’s positions in ASEAN. China appears to be using a similar playbook in the Pacific Islands, where substantial pledges of investment and aid have helped Beijing advance its policy preferences among members of the Pacific Islands Forum.64ABC/Reuters, “China gains the Solomon Islands and Kiribati as allies, ‘compressing’ Taiwan’s global recognition,” ABC News Australia, September 21, 2019, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-09-21/china-new-pacific-allies-solomon-islands-kiribati-taiwan/11536122. Farther afield, China has invested in Central and Southern Europe in an effort to weaken anti-China sentiment in the EU, though with less success.65Ivana Karásková et al., eds., “Empty shell no more: China’s growing footprint in Central and Eastern Europe,” Association for International Affairs, 2020, https://chinaobservers.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/CHOICE_Empty-shell-no-more.pdf.

In addition, Xi seeks both domestic and international legitimacy through grand, large-scale initiatives. The BRI is the most obvious example, and more recently, China has sought support for its GDI and GSI.66Lunting Wu, “China’s Transition From the Belt and Road to the Global Development Initiative,” The Diplomat, July 11, 2023, https://thediplomat.com/2023/07/chinas-switch-from-the-belt-and-road-to-the-global-development-initiative/. While these programs have served as vehicles for inducements, Beijing also uses economic incentives to entice noncommittal countries to sign on, bolstering the Chinese party-state’s political legitimacy at home and abroad. When Italy joined the BRI in 2019—the first Group of Seven (G7) government to do so—the move was highly touted by Beijing. Italy’s leaders were lured by promises of trade and investment, but the benefits were scarce. Italy withdrew from the initiative in 2023.67Ido Vock, “Belt and Road: Italy pulls out of flagship Chinese project,” BBC, December 7, 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-67634959.

The following two chapters will examine episodes in which China has successfully—or unsuccessfully—used positive incentives to induce desired changes in policy. Chapter 3 takes an in-depth look at the circumstances of Taiwan’s recent diplomatic losses and the prospects of maintaining its remaining partners; it concludes by addressing arguments about the relative importance of the formal diplomatic relations. Chapter 4 reviews several additional cases, expanding on China’s efforts in ASEAN, Italy, and other countries. Beijing’s use of quid pro quo inducements to achieve strategic goals should be of great concern to the United States as Washington seeks to counter Chinese influence.

Both China’s supply of positive inducements and the recipient country’s demand are necessary components of Beijing’s economic statecraft. Beijing has demonstrated a sensitivity to the political motivations and institutions of recipient countries that influence the acceptance or rejection of its strategic inducements. Further research into the development of China’s economic inducements—including communication of offers, identification of elites, and assessment of domestic needs, in addition to promise and delivery—would help shed light on how China is achieving strategic success and what factors the United States should prioritize in crafting an effective response.

Chapter 3: Taiwan’s fight for diplomatic recognition

The governments of China (the People’s Republic of China) and Taiwan (the Republic of China; ROC) have competed for diplomatic recognition since the Kuomintang (KMT) fled to Taiwan in 1949. Initially, both sides considered themselves the sole legitimate government of China, though today only Beijing holds this position.68Beijing has maintained this stance and seeks “unification” with Taiwan, even as the Chinese Communist Party has never ruled the island. Taiwan’s stance has shifted across administrations, with the current government holding the position that a declaration of independence is unnecessary because Taiwan is already independent. Chong Ja Ian, “The Many ‘One Chinas’: Multiple Approaches to Taiwan and China,” Carnegie China, February 9, 2023, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2023/02/the-many-one-chinas-multiple-approaches-to-taiwan-and-china?lang=en. No country maintains official diplomatic relations with both simultaneously.69Beijing requires its diplomatic partners to engage with Taiwan only unofficially. The Kuomintang’s Chiang Kai-shek initially did not allow for dual recognition, but over time, any policy position on this matter appears to have softened. More recent Taiwanese governments have indicated that there is no strict policy against diplomatic recognition of both China and Taiwan, though, in practice, instances of dual recognition have been transitory. Lu Yi-hsuan, “Taiwan could recognize dual relations with China,” Taipei Times, March 28, 2023, https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2023/03/28/2003796857; Edward A. McCord, “One China, Dual Recognition: A Solution to the Taiwan Impasse,” The Diplomat, June 20, 2017, https://thediplomat.com/2017/06/one-china-dual-recognition-a-solution-to-the-taiwan-impasse/. Taiwan held a coveted permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council since the world body’s founding in 1945 until China took over the position in 1971. Most countries have since switched recognition from Taiwan to China, including the United States in 1979. For the next few decades, Taipei and Beijing engaged in a competition over diplomatic recognition, with China gradually gaining the upper hand.70For a numerical count of Taiwan and China recognition since 1913, see “中華民國歷年邦交國數量” [The number of countries with diplomatic relations with the Republic of China by year], ROC History, January 15, 2024, https://ekinchiu.wixsite.com/rochistory/post/diplomatic-relations-over-the-years-quantity. This contest was termed “dollar diplomacy” (sometimes referred to as “checkbook diplomacy”) under the late Taiwanese president, Lee Teng-hui (1988–2000), a term now viewed as a derogatory in both Taiwanese and Chinese discourse.71Jessica Drun, Taiwan’s engagement with the world: Evaluating past hurdles, present complications, and future prospects, Atlantic Council, December 20, 2022, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/issue-brief/taiwans-engagement-with-the-world/.

In 2008, Taiwan’s election of President Ma Ying-jeou (2008–16)—a member of the KMT, which at this time advocated for a more reconciliatory approach toward China—eased Taiwan and China into a “diplomatic truce.” Beijing hoped that improved cross-strait relations under Ma would show the benefits of closer political ties between Taipei and Beijing and pave the way for unification. Beijing went so far as to reject efforts by Taiwan’s diplomatic partners to switch recognition.72Shih Hsiu-chuan, “WIKILEAKS: Cables detail rocky diplomatic relations,” Taipei Times, September 10, 2011, https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2011/09/10/2003512928. This report uses the term “diplomatic partner” to describe countries that recognize Taiwan; alliances traditionally imply mutual defense, though in practice “ally” and “partner” are often used as synonyms. See Rachel Tecott Metz, Jason W. Davidson, and Zuri Linetsky, “The Difference Between an Ally and a Partner,” Inkstick, February 15, 2023, https://inkstickmedia.com/the-difference-between-an-ally-and-a-partner/.

This truce held until the 2016 election of the Democratic Progressive Party’s (DPP’s) Tsai Ing-wen (2016–24) as Taiwan’s president. Tsai and the DPP were viewed negatively in Beijing as advocates of independence, though the former president professed a desire to maintain the status quo.73Ching-hsin Yu, “The centrality of maintaining the status quo in Taiwan elections,” Brookings Institution, March 15, 2017, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-centrality-of-maintaining-the-status-quo-in-taiwan-elections/. Regardless of the truth, Beijing sought to convince Taiwanese citizens that the DPP was unable to protect Taiwan, often resorting to coercive tactics in bilateral relations, including cutting off all communication, conducting naval exercises around the island, and imposing trade and travel restrictions.74Jermyn Chow, “Sao Tome’s decision to cut diplomatic ties is unfriendly and reckless, says Taiwan,” Straits Times, December 21, 2016, https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/east-asia/china-welcomes-sao-tomes-decision-to-cut-diplomatic-relations-with-taiwan. The CCP has continued and expanded these tactics following the election of the DPP’s Lai Ching-te in 2024.75For example, see Ben Blanchard, “Taiwan says China uses record number of aircraft in war games,” Reuters, October 15, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/taiwan-details-record-surge-chinese-warplanes-involved-war-games-2024-10-15/.

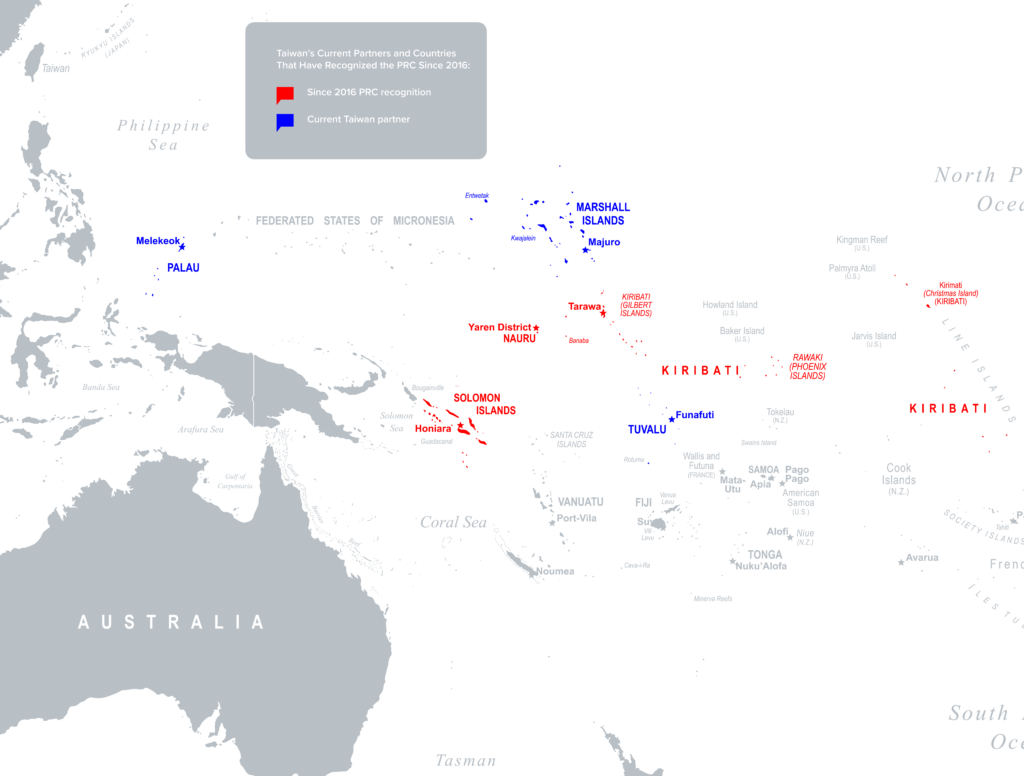

China’s measures against Taiwan under DPP leadership have included poaching Taipei’s diplomatic partners. At the beginning of the Ma administration, Taiwan was recognized by twenty-three countries; as of early 2025, that number has shrunk to twelve (including Vatican City), with eleven countries recognizing China since Tsai’s election. These countries are The Gambia, São Tomé and Príncipe, Panama, the Dominican Republic, Burkina Faso, El Salvador, the Solomon Islands, Kiribati, Nicaragua, Honduras, and Nauru. How has China been able to convince so many of Taipei’s diplomatic partners to change allegiance?

The key to Beijing’s success lies in the use of positive economic inducements, buttressed by the promise of economic growth and investment. While additional variables are at play—including “subversive carrots,” coercion, and personal ties—recent switches have been accompanied by lavish promises of aid, investment, and trade. As with many of China’s economic overtures and promises, exact numbers are difficult to parse—and delivery is even more difficult to ascertain. Still, the majority of switches have occurred with an identifiable set of economic incentives attached, including trade agreements, infrastructure deals, investment promises, grants for specific purchases, and contributions to political funds. These incentives often meet domestic economic development needs that offer the host government—whether democratic or autocratic—the opportunity to boast of its ability to deliver public goods and services to its population. Many of the diplomatic switches came in close proximity to elections, as noted in each vignette described below.

This ability to trumpet broader benefits to a country’s population is one reason that corruption and “subversive carrots” are—if present—typically part of a larger package of promises. Allegations of corruption are present in several of the poaching case studies, though it is worth noting that Taiwan has also been accused of engaging in questionable tactics.76In Papua New Guinea, for example, a Singaporean businessman reportedly sought to bribe officials with money from the Taiwanese government. As described later, Taiwan’s contributions to Rural Constituency Development Funds in the Solomon Islands have come under scrutiny. Steve Marshall, “PNG businessmen named in Taiwan diplomacy bribe,” ABC News (Australia), October 14, 2008, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2008-10-15/png-businessmen-named-in-taiwan-diplomacy-bribe/542240; “Taiwan-Solomon Islands Relations and China’s Growing Inroads into the Pacific Islands,” Global Taiwan Brief (Global Taiwan Institute) 4, no. 13 (July 3, 2019), https://globaltaiwan.org/2019/07/taiwan-solomon-islands-relations-and-chinas-growing-inroads-into-the-pacific-islands/. Personal gain and corruption can push a policymaker or politician into taking a policy position that benefits China, but in most political systems—even authoritarian ones—citizens (as well as businesspeople and other policymakers) have some expectation that the public will benefit from the policy in question. When it comes to China, this means there is usually a public good on offer, which can include promises of loans, investment, trade, and/or grants in support of infrastructure projects.

These offers are particularly attractive because of the underlying economic dynamics at play. Countries considering a switch cannot ignore the pull of China’s market—particularly in relation to Taiwan’s.77“China welcomes El Salvador to jointly build Belt and Road,” CGTN, December 4, 2019, https://news.cgtn.com/news/2019-12-03/Xi-holds-welcome-ceremony-for-visiting-Salvadoran-president-M7Jd05efCM/index.html; interview, representative of current diplomatic partner, June 2024. Open access to Chinese trade flows, investment, and aid is enticing on its own, and many of Taiwan’s former partners had commercial ties with Chinese companies and individuals in the years prior to switching diplomatic recognition.

Case studies

Taipei is currently left with twelve remaining diplomatic partners. Between 2000 and 2008—the start of the temporary truce in the diplomatic contest during the Ma administration—eight countries switched recognition: Macedonia (2001), Liberia (2003), Dominica (2004), Grenada (2005), Senegal (2005), Chad (2006), Costa Rica (2007), and Malawi (2008).78“El Salvador establishes diplomatic relationship with Beijing, cuts ties with Taiwan,” CGTN, August 24, 2018, https://news.cgtn.com/news/3d3d514d354d6a4e79457a6333566d54/index.html. Since the pause ended in 2016, eleven additional countries have recognized China at Taiwan’s expense.

The vignettes that follow describe the circumstances of each of the eleven countries that have switched recognition since Tsai’s election, including reported amounts of inducements and any domestic political development in these countries. In pursuit of analytical clarity, these descriptions focus on changes in diplomatic recognition after The Gambia in 2016. Restricting the analysis to this period keeps the ruling regimes in China (Xi) and Taiwan (DPP) constant. These vignettes emphasize developments in China and Taiwan’s relationship with each country, primarily in relation to the switch in recognition. Put together, these case studies offer a systematic analysis of China’s strategy and the circumstances surrounding each switch. Each vignette begins with a quote—their purpose is to highlight the precariousness of Taiwan’s position, not to call out the politicians who made these statements.

Following these discussions, the next section reviews Taiwan’s remaining partners to assess China’s efforts in those countries and the likelihood of a diplomatic switch in the foreseeable future. The chapter concludes with a review of three common arguments as to why Taiwan should not concern itself with its formal partners—geopolitics, economics, and values—and offers two reasons that Taipei and Washington should have a vested interest in maintaining Taiwan’s formal relationships in their current state. In short, deterrence relies on China’s perception of Taiwan and the United States’ willingness to confront Beijing in attempts to degrade Taipei’s ability and willingness to uphold its sovereign rights. Taiwan’s international legitimacy is part of this larger calculus.

Nauru

“Nauru regards Taiwan as kin, standing firmly in our support and laboring hand-in-hand to advance democracy, freedom, peace, sustainability, stability, and economic growth in our region.” – Nauruan President Russ Kun during a national day celebration visit to Taiwan on October 9, 202379Office of the President, Republic of China Taiwan, “President Tsai and President Russ Joseph Kun of Nauru hold bilateral talks,” news release, October 9, 2023, https://english.president.gov.tw/NEWS/6615.

Dates of switch: January 15, 2024 (break with Taiwan), January 24, 2024 (switch to China)

Reported ask of Taiwan: $83 million

Reported inducements from China: $100 million/year in aid

Post-switch agreements: Ten MOUs

Relation to domestic politics: President David Adeang (2024–) sworn into office on October 31, 2023, after a vote of no-confidence through parliament against Russ Kun (2022–23)

In January 2024, Nauru became the most recent country to switch allegiance from Taiwan to China. The move came just days after the election of the new Taiwanese president and was widely viewed as an expression of Beijing’s disapproval. The government of Nauru declared recognition of China as “in the best interests” of the country and its people. Media reported China’s promises to Nauru at $100 million a year, citing a senior Taiwan official.80Kirsty Needham and Yimou Lee, “Taiwan loses ally Nauru, accuses China of post-election ploy,” Reuters, January 15, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/taiwan-loses-first-ally-post-election-nauru-goes-over-china-2024-01-15/. Taiwanese media alleged that Nauru had asked Taipei for $83 million to cover the budget shortfall from the closing of Australia’s Regional Processing Centers for refugees.81Paul Millar, “China’s Pacific charm offensive pays off as Nauru drops Taipei for Beijing,” France 24, January 16, 2024, https://www.france24.com/en/asia-pacific/20240116-china-s-pacific-charm-offensive-pays-off-as-nauru-drops-taipei-for-beijing; Jamie Seidel, “Key nation ditches Taiwan for China, leaving Australia in the dust,” news.com.au, January 22, 2024, https://www.news.com.au/finance/economy/world-economy/key-nation-ditches-taiwan-for-china-leaving-australia-in-the-dust/news-story/73abc851f2ae64784e11cfa57edf0165; Meg Keen and Mihai Sora, “Nauru’s diplomatic switch to China – the rising stakes in Pacific geopolitics,” Interpreter, January 18, 2024, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/nauru-s-diplomatic-switch-china-rising-stakes-pacific-geopolitics. Nauru has since committed itself to its new relationship with China, and President David Adeang visited Beijing in March 2024.82“Full text: Joint statement by China and Nauru,” CGTN, March 26, 2024, https://news.cgtn.com/news/2024-03-26/China-Nauru-vow-to-expand-pragmatic-cooperation-1shOk5TFuRG/p.html. During the visit, the Nauruan president signed ten MOUs on a wide variety of areas, including economic development, trade, the BRI and GDI, banking, green and digital development, and media cooperation.83“China developments are for Nauruans: HE Adeang,” Nauru Bulletin #7, Government of the Republic of Nauru, May 3, 2024, https://www.nauru.gov.nr/government-information-office/nauru-bulletin/nauru-bulletin-2024/nauru-bulletin-7.aspx.

Nauru’s diplomatic switch came just a few months after Adeang’s predecessor was ousted in a no-confidence vote in October 2023. Former President Russ Kun had been supportive of his government’s relationship with Taiwan, and the no-confidence vote raised uncertainty in Taipei regarding the next president’s stance. Initially, Adeang was viewed as largely supportive of Taiwan, and concerns over a potential switch were mollified when Nauru accepted a new Taiwanese ambassador in December 2023.84Jono Thomson, “Taiwan approves new ambassador to diplomatic ally Nauru,” Taiwan News, December 10, 2023, https://www.taiwannews.com.tw/news/5056463.

Major Chinese firms were involved in Nauru for some time prior to the switch. China Harbour Engineering Company (CHEC), a major Chinese state-owned construction firm, was leading the redevelopment project for Aiwo port, supported by the Asian Development Bank (ADB), and slated to be completed in 2025.85“Australia pays controversial Chinese company millions for Nauru’s new port,” Islands Business, April 23, 2024, https://islandsbusiness.com/news-break/australia-pays-controversial-chinese-company-millions0for-naurus-new-port/. Australian authorities noted “suspicious” payments from CHEC flowing to a Nauruan official who pushed for the diplomatic switch.86Ibid. The Aiwo project was noted at the March 2024 state visit to Beijing as one area in which to deepen cooperation. CHEC also has a solar farm project in Nauru.87“China developments are for Nauruans.” In 2021, Nauru had helped scuttle a proposal from a Huawei subsidiary to build an undersea communications cable to connect Nauru to an Australian network.88Jonathan Barrett, “EXCLUSIVE Pacific island turns to Australia for undersea cable after spurning China,” Reuters, June 24, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/exclusive-pacific-island-turns-australia-undersea-cable-after-spurning-china-2021-06-24/.

Despite the diplomatic switch, China’s dominant influence in Nauru is far from assured. In December 2024, Nauru and Australia signed an agreement declaring the two sides have to mutually agree on any engagement in Nauru’s security, banking, and telecommunications sectors, as well as other critical infrastructure.89“Australia gains effective veto over Nauru security pact,” Islands Business, December 11, 2024, https://islandsbusiness.com/news-break/australia-gains-effective-veto-over-nauru/. The pact—coming after China has pushed security and policing agreements in other Pacific Island countries—is a significant hold on Beijing’s encroaching influence. With a population of 12,500, Nauru depends on Australia for development assistance and banking services and generates much of its revenue from fishing licenses.

Nauru had previously recognized China between 2002 and 2005, for which it was promised $137 million in grants and debt repayment from Beijing.90Millar, “China’s Pacific charm offensive.” In exchange for switching back to Taipei—an example of “yo-yo diplomacy”—Taiwan funded Nauru’s purchase of a Boeing 737 jet in 2006.

Honduras

“We hope to deepen such friendship and diplomatic ties ….” – Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández during a surprise visit to Taiwan on November 13, 202191“‘We are real friends’: Honduran president says in Taiwan visit amid China tension,” Reuters, November 13, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/china/we-are-real-friends-honduran-president-says-taiwan-visit-amid-china-tension-2021-11-13/.

Date of switch: March 26, 2023