WASHINGTON – The US president’s power to pardon is both one of the most absolute and misunderstood provisions of the Constitution.

Rooted in the “prerogative of mercy” of English kings dating back to the seventh century, the founders wanted a robust pardon power to allow “easy access to exceptions in favour of unfortunate guilt” by the justice system, as Alexander Hamilton wrote.

Today, the power has become as polarising as the men using it.

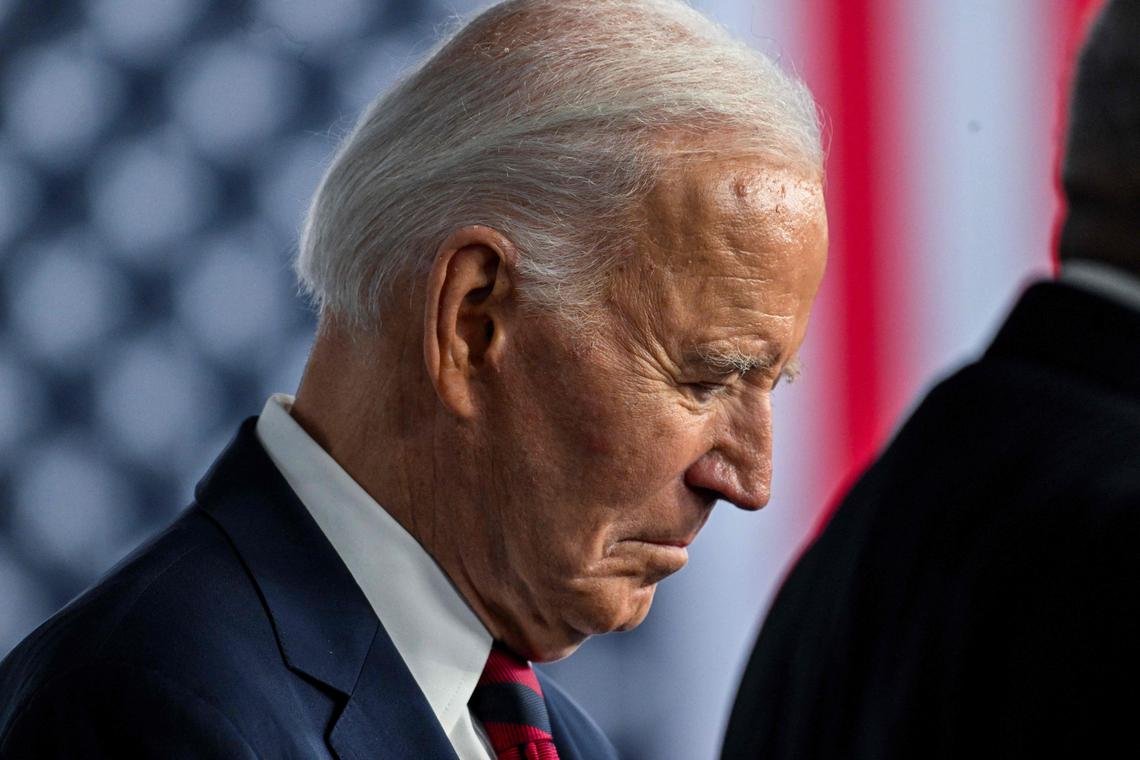

In his last weeks in office, President Joe Biden pardoned his son Hunter from convictions on tax and gun violations, released 1,499 convicts serving home confinement – including some convicted of public corruption – and commuted 37 death sentences.

In the last week of his presidency, he shortened the sentences of 2,490 drug offenders who he said received disproportionately long sentences. And he is considering 11th-hour pardons for political allies that President-elect Donald Trump has suggested he would prosecute.

In all, Mr Biden’s 65 pardons and 4,161 commutations have made him the most prolific employer of presidential clemency in history, granting it more times in a single term than all of his last seven predecessors combined.

And Mr Trump, who granted sweeping pardons to dozens of political friends himself during his first term, has promised to pardon allies he says were unfairly prosecuted during the Biden years – including many of the hundreds of people convicted for their actions in the riot at the US Capitol on Jan 6, 2021.

What is a pardon?

A pardon is the legal forgiveness of a crime granted by a president, governor or other executive authority. While in some US states the governor shares the power with a pardon board, the power to pardon federal crimes is the president’s alone.

It’s not an expungement; the conviction remains on the record. Nor is it a statement on either the guilt or innocence of the individual.

Pardons come under the broader presidential power of executive clemency, which also includes lesser forms of presidential mercy, such as:

- Commutations, which reduce the sentence but leave all other consequences of the conviction intact.

- Reprieves, which delay the imposition of a sentence.

- Remittances, which lower or eliminate monetary fines.

Reprieves and remittances are rare in modern times.

How often do presidents pardon?

Every president except two – William Henry Harrison and James Garfield, who died in office – has issued pardons. Cumulatively, presidents granted almost 35,000 individual acts of clemency, beginning with the first known pardon by George Washington for the offence of smuggling rum from Barbados in casks smaller than 189 litres.

But the power has generally fallen into relative disuse in recent decades. In modern times, presidents tend to grant clemency around the holidays and at the end of their terms.

Why do presidents exercise their pardon power?

In granting a pardon, a president is often communicating his views on justice, mercy, norms and social mores.

The list of those receiving pardons reads like a social history of the US, as presidents seek to heal old conflicts and reconcile the country to a more punitive past. Wars, insurrections, prohibition, the war on drugs – all have been followed years or decades later by rounds of clemency.

In a clear precedent for Mr Trump’s planned pardons of Jan 6 insurrectionists, Washington himself pardoned 10 ringleaders of the tax protest known as the Whiskey Rebellion in the 1790s who had been convicted of high treason. Presidents Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson pardoned Confederate soldiers and Gerald Ford pardoned their general, Robert E. Lee.

Some pardons are seen as being more motivated by self-interest.

President Richard Nixon pardoned influential US labour leader Jimmy Hoffa, who had been convicted of jury tampering and fraud and later supported Nixon’s reelection bid. Mr Bill Clinton pardoned financier Marc Rich, the husband of a major campaign donor, after Rich had been indicted for tax evasion and striking oil deals with Iran during an embargo.

Are there any limits on pardons?

The founders intentionally created the pardon power with few strings attached. Hamilton wrote that it “should be as little as possible fettered or embarrassed”.

The Supreme Court has held that because it’s a power explicitly given to the president in the Constitution,“its limitations, if any, must be found in the Constitution itself”.

In other words, a pardon is valid as long as it does not violate some other provision of the Constitution. Those cases are undoubtedly narrow; some commentators have argued that acceptance of a bribe for a pardon could possibly invalidate it, but even that is not clear.

The Constitution does contain two clear limitations.

Presidents can grant pardons only for “offences against the United States”, meaning only federal and not state crimes. And there’s an exception for cases of impeachment: the president cannot use the power to frustrate the power of Congress to remove him or other officials.

Can a presidential pardon be revoked?

Neither Congress nor the courts have the power to overturn presidential pardons. However, a president can revoke a pardon if the documents have not yet been delivered to and accepted by the person receiving clemency.

Mr George W. Bush in 2008 granted a pardon to real estate developer Isaac Toussie, who had been convicted of mail fraud. But just a day later, after learning Toussie’s father had made donations to Bush’s Republican Party, the president reversed his decision and instructed that the pardon not be given.

Because Toussie had not received the paperwork, the clemency did not take effect.

A president could similarly attempt to revoke an undelivered pardon issued by a predecessor.

In 1869, Andrew Johnson awarded pardons to three people convicted of fraud. But just days later, President Ulysses S. Grant took office and recalled the members of the US Marshals Service delivering the paperwork, and the pardons were withdrawn.

Can the president pardon himself?

Most legal scholars say he cannot, based in part on the plain language of the power.

The Constitution says that the president has the power to “grant” pardons, which means to “bestow” or “transfer” them – in other words, give them to someone else.

In addition, in a legal memo crafted just before Nixon’s resignation in 1974, the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel held that the president cannot self-pardon “under the fundamental rule that no one may be a judge in his own case”. In any event, Ford pardoned Nixon for any alleged Watergate crimes.

But the question has never been tested, and even scholars who oppose the idea of the self-pardon concede that it’s an open question. Regardless, there’s a workaround: A president could temporarily cede power to the vice president, who could issue a pardon as acting president.

Can someone be pardoned preemptively?

The president cannot grant a pardon for a crime that has not yet been committed, which would be the equivalent of a lifetime get-out-of-jail-free card.

But a person can be pardoned after committing a crime and before any charges have been brought.

A seminal 1866 Supreme Court case dealing with Confederate soldiers, Ex parte Garland, held that the pardon power “extends to every offence known to the law, and may be exercised at any time after its commission, either before legal proceedings are taken or during their pendency, or after conviction and judgment”.

Can someone be given a ‘blanket’ pardon?

Yes. A president does not need to identify the crime committed in order to issue a pardon. The most famous example is Ford’s pardon of Nixon for all offences carried out while he was president.

Mr Biden’s pardon of Mr Hunter Biden included the gun and tax evasion charges for which he was convicted, but also any other offences he may have committed for the previous 11 years.

And Mr Trump pardoned a number of allies, including former political adviser Stephen Bannon and Albert Pirro Jr, the ex-husband of Fox News host Jeanine Pirro, for unspecified “offences against the United States individually enumerated and set before me for my consideration”.

Does accepting a pardon mean admitting guilt?

No. Presidents have granted pardons, often to people they believed to be innocent or otherwise victims of injustice.

For example, Mr Trump posthumously pardoned boxer Jack Johnson, who was convicted in 1913 of transporting a woman across state lines for “immoral purposes” – a crime that frequently formed the basis of racist prosecutions. Mr Biden pardoned service members convicted of violating a now-repealed military ban on consensual gay sex.

The popular notion that a pardon implies guilt comes from a 1915 Supreme Court ruling in the case of Burdick v. United States, which said that a pardon “carries an imputation of guilt; acceptance a confession of it.” Ford kept a dog-eared copy of the decision in his wallet as vindication of his pardon of Nixon.

But later courts have not viewed that “imputation of guilt” as essential to the Burdick decision, which held that someone granted a pardon has the right to refuse it.

Does a pardon have to be in writing?

“The answer is undoubtedly no,” a federal appeals court ruled in February 2024. “The plain language of the Constitution imposes no such limit.”

But as a practical and historical matter, it helps to have a record.

In that 2024 decision, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that Mr Trump’s verbal statement to former Cleveland Browns running back Jim Brown that “I’m gonna do this” and “I want this done” were not enough to free a man serving a life sentence for drug trafficking and murder.

Does the president have to identify who he’s pardoning?

No again. There’s a history of categorical pardons, granting clemency for everyone convicted of a certain offence.

President Jimmy Carter used this power to give amnesty to draft dodgers after the Vietnam War and Biden used it for marijuana offences, for example. In those cases, people convicted of the specified crime can apply to the Office of the Pardon Attorney in the Justice Department, for a certificate that verifies they’re covered by the pardon.

How does someone get a pardon?

There are two procedural paths.

The first, which President Barack Obama followed, required someone seeking a pardon or commutation to file with the Office of the Pardon Attorney. The office generally considers applications only after a five-year waiting period, and won’t consider posthumous pardons or those for misdemeanours. After a thorough review – including an FBI background check – the recommendation goes to the attorney general, the White House Counsel’s Office and then to the president, who may grant or deny it.

The second model, favoured by Mr Trump, is much looser. He often took recommendations from celebrities such as Kim Kardashian and Sylvester Stallone, skipped the waiting period and background check, and signed pardons in pomp-filled ceremonies.

Most presidents use a combination of the two, with the more controversial pardons often following the direct path to the president.

One reason to bypass the bureaucracy: The backlog of pardon applications reached record highs under Mr Biden before his latest grants brought the logjam down to pre-Trump numbers. BLOOMBERG

Join ST’s Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.