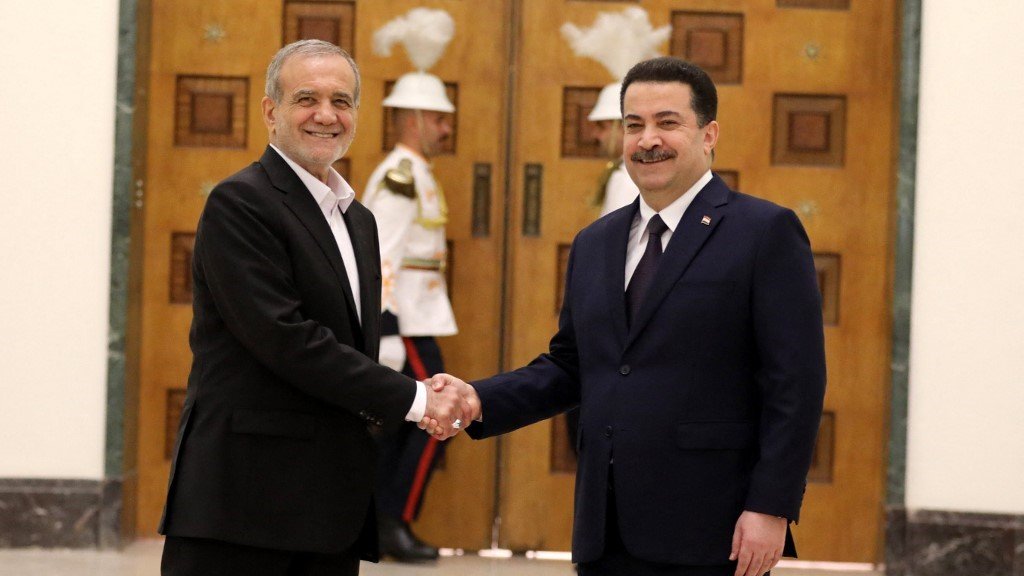

Iran‘s President Masoud Pezeshkian touched down in Iraq on Wednesday in his first trip abroad since becoming president in July.

Pezeshkian, a member of the reformist political camp who was elected following the death of his principlist predecessor in a helicopter crash, was set to discuss the deepening of security and economic ties between the neighbours.

A number of issues are on the agenda, including increasing trade relations to help lessen the impact of US-imposed sanction on Iran, as well as Israel’s war on Gaza and its effect on the region.

One longstanding sore between the two countries Pezeshkian is also looking to tackle, however, is the continuing presence of Iranian Kurdish separatist movements in Iraq.

Baghdad and Tehran signed a security agreement in March 2023 that saw Iraq push a number of armed factions away from the Iranian border and restrict their activities, after the Islamic Republic blamed the groups for fomenting women-led protests in Iran in 2022.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

In an interview with state media on Tuesday, Kazem Gharibabadi, an official in the Iranian judiciary, said his government had issued a formal request to Iraq for the extradition of 118 “key members” of the groups.

“The Iranian judiciary has the duty to pursue and prosecute terrorists… due to the terrorists’ hiding in Iraq, our demand from the Iraqi government is the extradition of the criminals residing in that country,” he said.

On Saturday, the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (PDKI) said one of its leading members, Behzad Khosrawi, had been handed over to “Iranian intelligence”.

Local security services for the semi-autonomous Kurdistan region in northern Iraq said Khosrawi’s transfer was due to his not having “residency” in Iraq and denied it was politically motivated. But some of the groups are increasingly worried their days could be numbered.

‘The Iranian regime is aware that the influence of the Kurdish parties is significant among the general public’

– Keywan Faramarzi, Komala party

“It follows that the primary objective of the Iranian president’s visit to Iraq is to implement the security agreement between Tehran and Baghdad – to disarm the Iranian Kurdish parties based in the Kurdistan region and close their military camps,” Keywan Faramarzi, a representative of Komala, one of the Iraq-based groups, told Middle East Eye.

In 2023, Komala, a left-wing group, saw its camps adjacent to the Iranian border partially evicted. Last week, the eviction was apparently completed after Komala was moved along with two other groups to a “less accessible” location.

Faramarzi said that it had become “increasingly challenging” for Iranian Kurdish parties to operate in northern Iraq, noting the growing influence of Iranian intelligence and the cooperation of Iraqi Kurdish officials.

“The Iranian regime is aware that the influence of the Kurdish parties is significant among the general public,” he said.

“For instance, the movement for Women, Life, Freedom two years ago was a testament to the unity and solidarity of the people of Kurdistan, which was led by the Kurdish parties,” he added, in reference to the 2022 protests.

Faramarzi believes following the new extradition request, the next step could be the banning of Kurdish Iranian parties and the assassination of their members by Iranian operatives.

Thorns in Iran’s side

There are four Iranian Kurdish parties based in northern Iraq that Tehran has sought to tackle: the PDKI, who are ideologically aligned with the ruling establishment in Iraqi Kurdistan; the left-wing Komala party; the Kurdistan Freedom Party (PAK); and the Free Life Party of Kurdistan (PJAK), a group affiliated with the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), the armed movement that has fought Turkey for decades.

Several of these groups have been in operation since before the establishment of the Islamic Republic and have fought successive administrations for Kurdish autonomy.

The PDKI was founded as early as 1946, struggling against the US-backed Pahlavi monarchy for an independent state.

“The Iranian regime is the enemy of the Kurds – it’s not the first time, it’s not the last time,” PDK-I deputy chief Amanj Zebaii told MEE.

The PDK-I, in particular, has faced the brunt of much of Iran’s retaliation in the wake of the 2022 protests, with several Iranian air strikes targeting their bases in northern Iraq.

Zebaii said it had also been attacked by Iranian “proxies” in Iraq and said the group’s members always found themselves in a “dangerous situation” a result of Iran’s operations against the group.

Last year, Iran gave Iraq a 19 September deadline to disarm Kurdish groups on the border and move their bases, threatening to take matters into its own hands if Baghdad did not comply.

Iraqi officials say that work has now been completed, but the groups’ continuing presence within the country has continued to irk their eastern neighbour.

“The PDKI respects Iraqi law,” Zebaii told MEE.

“We are a political party, but absolutely we have guns, [but] our guns are just for self-defence.”

‘Just for show’

Pezeshkian is set to visit regions across Iraq during his visit, including Kurdistan on Friday at the invitation of the region’s president, Nechirvan Barzani.

“Relations between Iran and the Kurdistan region are currently good, and with God’s help, we are trying to strengthen them,” he told Kurdish news outlet Rudaw after landing in Baghdad, speaking to them in Kurdish.

As the first member of Iran’s reformist camp elected in almost 20 years – as well as a member of Iran’s Azerbaijani minority – there had been some hopes in Iran that he might loosen some of the heavy-handed security measures imposed across the country since the 2022 protests, which were sparked by the killing of a Kurdish woman in police custody.

Pezeshkian publicly voiced concerns about Mahsa Amini’s death, as well as the security services’ fierce response to the protests, which saw almost 600 people killed.

And in terms of foreign relations, there have been hopes that he can calm regional tensions following a period that has seen Iraq used as a theatre for attacks by various regional and international players – including a strike in January in Kurdistan where Iran’s Revolutionary Guard said it targeted Israeli intelligence headquarters.

But these murmurs of optimism have been dismissed by many of the Islamic Republic’s foreign-based opponents, who say he is ultimately irrelevant in the hierarchy compared to Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei or the Revolutionary Guard.

“Pezeshkian is one person, just for show,” Zebaii said.

While Iran’s ruling establishment tried to paint the Mahsa Amini-inspired protests as stoked and shaped by Iranian Kurdish forces outside the country, those same groups are eager to take credit themselves, despite the demonstrations reaching far beyond the Kurdish community or solely Kurdish-focused issues.

They hope a fresh wave of anti-establishment protests will be even more effective at rocking the Islamic Republic and its leaders.

“This time we are ready for the second Iranian revolution: women, life, freedom,” said Zebaii.

“The PDKI have an important role in all of these revolutions, especially in Kurdistan and Iran – we are ready for this.”