Summary

- Europe is in a culture war with Trump’s America.

- Part of this involves Trumpists propping up their ideological allies in European politics. A deeper level involves humiliating Europeans in their dealings with the US. The two intertwine to tell a single story.

- Trump and his acolytes can only do this because Europeans let them. At the first level Trumpists exploit polarisation in societies and the rise of Europe’s “new right”. At the second they take advantage of division and hesitation among European leaders.

- It doesn’t have to be this way. A decade of crises has strengthened European sentiment among the public. Almost all member states still have mainstream-led, pro-European governments.

- This should give the EU’s politicians the courage to act—and defend a Europe that writes its own script.

- That would also help preserve a strong transatlantic alliance; one in which the EU and European countries are America’s peers, not its subordinates.

A fogged mirror

After a long moment, a hand wipes the condensation from the glass to reveal the face of TRUMAN BURBANK.

(Andrew M. Niccol, 1998)

Europe is stuck in a Truman Show, and Trump’s America is in the director’s chair.

In Andrew Niccol and Peter Weir’s 1998 film, the titular character struggles through life unaware his every up and down is broadcast as a reality show. Orchestrating the action is the show’s all-powerful executive producer, Christof—who, for the benefit of his product, manipulates Truman’s world and his mind. When our protagonist uncovers the truth, he faces a quandary: should he leave the comfort of the only reality he knows? And if so, how can he find the exit?

Like Truman, Europe’s leaders now spend their days dealing with dramas largely not of their making. One day the task is to avoid a trade war with America; the next it is to ensure continued US commitment to European security in the face of a belligerent Russia. They combine this with managing political polarisation at home, some of which is actively stoked by President Donald Trump and his MAGA movement.

Ursula von der Leyen embodied Europe’s new reality in her state of the union address on September 10th. The European Commission president did not shy away from the fight the EU faces to determine its own destiny—but the pressing matters of economy and security meant there was little room in the speech for culture (or indeed Trump). It took French MEP Valerie Hayer to suggest the EU was in a culture war, and that the assault on Europe’s values and ideals was not only coming from the east. As I wrote in June, however, a failure to defend European values at this very moment is to misunderstand the threat Trump poses to Europe.

This paper goes further. It argues that most of what is happening in today’s transatlantic relationship is part of the culture war. The drama plays out at two levels. The first is an ideological conflict over which values dominate European politics and define the West. The second is deeper and more subtle: this is a struggle for the EU’s dignity, credibility and identity as an autonomous actor on the global stage. The two dynamics intertwine to such an extent that they tell a single story. But the time has come for Europeans to leave this artificial reality and become protagonists—not props—in their own show.

The good news is that conditions are primed for them to do so. “European sentiment”—the sense of belonging to a common space, sharing a common future and subscribing to common values, which is best observed against the background of major shocks and events—remains strong across the EU.

Read more about EUROPEAN SENTIMENT.

In several countries, public and political appreciation for the EU is growing—not necessarily out of idealism, but from a pragmatic belief that collective action matters in a volatile world. The early months of Trump’s presidency likely turbocharged this. They seem to have clarified the very values, such as rule of law and protection of fundamental rights, that many citizens want Europe to embody. This strengthens the case for a more geopolitical EU. It should embolden leaders internationally and energise liberals at home. For now though, Europe’s leaders seem to know the truth but are not yet ready to walk off set.

The paper begins on Trump’s soundstage. It builds on research from across the EU27 to show how Trumpists seek to shift the ideological centre of gravity in European politics, thus implementing what Celia Belin calls “Trump’s plan for Europe”. It then examines how the US leadership undermines European identity, and how the two levels form a single culture war. Next it expands on the state of European sentiment in 2025, highlighting both the strengths policymakers should build on and the obstacles they face. Finally, it shows Europeans the exit—and what may await them if they have the courage to use it.

One small scene in “The Truman Show” brings the analogy full circle. As Truman is buying a magazine one day, a man behind him holds up a newspaper emblazoned with the headline: “Who Needs Europe!” Christof’s artificial slice of America, Seahaven, is perfect and self-sufficient, with no need for what lies across the Atlantic. The reminder is apt: in Trump’s culture war, the idea of “Europe” itself—more than any leader, party or policy—is the main target.

This is the fourth edition of the annual European Sentiment Compass, a joint initiative by ECFR and the European Cultural Foundation. It is based on research by ECFR’s 27 associate researchers in summer 2025, alongside other sources—including ECFR’s previous public opinion polls.

Tump’s big, beautiful soundstage

CHRISTOF

We accept the reality of the world with which we’re presented.

(Andrew M. Niccol, 1998)

A culture war runs deeper than disputes about policy. It is also a struggle over values, identity and the symbolic boundaries that define who “we” are. Such a conflict plays out accordingly: through policy, but also through symbols, narratives and acts of meaning-making. Europe and America share a political system and its reference points. They both claim authority to define “the West” and its values, including what democracy and freedom should be about. For decades, that authority was assumed to be aligned. Now, largely at Trump’s behest, it has become contested ground.

Part of the contest happens “frontstage”—in full view of the cameras. These are the high-drama ideological battles over migration, climate, “wokeism” and free speech. This is the struggle over which debates dominate European politics and the meaning of “Western values”. It largely predates Trump, with powerful domestic drivers explaining the rise of the European “new right”. But Trump’s America is building on these foundations to wage its own culture war in Europe. This means Europe’s governments and their “liberals” spend most of their energy reacting to crises scripted by Trump and his European allies, rather than setting the agenda themselves.

This paper uses LIBERALS and MAINSTREAM interchangeably to describe all parties from the centre-right to centre-left that subscribe to Europe’s post-1945 model of liberal democracy, and which have been central in shaping the liberal order at home and through international institutions.

It contrasts them with the NEW RIGHT. These political forces vary in their extremism, but all present themselves as an alternative to the liberal consensus of the past decades. They denounce what they see as the errors of liberalism (for example, on free trade, migration and international integration), and focus on national sovereignty, rejecting inclusive policies—and, ultimately, arguing the entire system needs an overhaul in their image.

There is plenty of drama “backstage”, too. This is the contest over Europe’s identity—its agency to act in the world and its status as a peer in the transatlantic relationship. Trump and his team repeatedly characterise Europeans as naive, dependent and lacking in strategic maturity. The effects are more subtle than in the struggle over values. Europe’s leaders can dismiss trade fights as mere trade fights; NATO debates as just routine disputes about burden-sharing that hark back to the early days of the alliance; Trump’s transactionalism as the result of an America simply fed up with its global obligations. But if European leaders and societies internalise the humiliations, they could result in cultural subordination.

Still, Trump can only do this because Europeans let him. Frontstage, Trumpists exploit genuine polarisation in societies and the rise of the “new right”. Backstage, they draw on real division and hesitation among Europe’s leaders—as well as countries’ real or imagined dependencies on the US and exposure to American influence. The paradox is that this is happening against a backdrop of strong European sentiment across the EU.

Read an OVERVIEW and COUNTRY PROFILES of European sentiment in 2025.

Imperfect as the EU is, and despite its recent failures (such as a muted and incoherent response to Binyamin Netanyahu’s Israel), the union remains a haven of liberal democracy for most of its citizens, and a symbol of that for many people around the world. In many ways, Europe remains a promise—one that Trump’s America could be on course to break.

Frontstage

If one were to pinpoint the moment Trump’s America openly declared a culture war on Europe, it was J.D. Vance’s infamous speech at the Munich Security conference (MSC) in February. America’s vice president used his pulpit, just days before the German federal election, to sketch a transatlantic clash over democracy itself. He accused Europe of retreating from the “fundamental values shared with the United States”. He denounced the postponement of Romania’s November 2024 presidential election (the first round of which was annulled after accusations of Russian meddling), warning the same might happen in Germany “if things don’t go to plan”. Vance also devoted a full ten minutes to lamenting the “retreat” of free speech in Europe; and to wrap up, castigated centrists for ignoring voters concerned about “millions of unvetted migrants”.

This did not happen in a vacuum. Across Europe, the new right has stalked liberals for at least a decade. New-right forces are in government in Italy and Hungary, and are climbing up the polls in much of Europe. Most of their rise has domestic roots. But the second Trump presidency has further normalised what once seemed radical. Now, extreme positions gain legitimacy from the US president himself, whether that is on migration, Islam, climate, or minority and women’s rights.

Trump does more than provide credibility (as well as framing and coherence) to Europe’s new right. His orbit also provides the critical infrastructure—conferences, media ecosystems, funders and ideological avant-gardes—that supports the formation of a “MAGA internationale”. Or, as Ivan Krastev and Mark Leonard call it, the “post-liberal revolution” that is on course to establish its own order. This infrastructure ranges from the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) to the activism and reach of Trump’s erstwhile buddy, Elon Musk. At one rally, Marine Le Pen hailed “a global tipping point”. Echoing the grand dame of France’s National Rally (RN), Hungary’s prime minister Viktor Orban declared: “We are the future.”

Trumpists work to shape that future using three main techniques: an open willingness to interfere in European elections; a deliberate framing of EU-US relations as a values divide; and a new emphasis on free speech as a rallying point for Europe’s new right.

Only they can save Europe

Vance hinted at MAGA’s “saviour complex” in Munich. His speech saw him decry the absence of new right leaders from the stage, and the next day he held a taboo-busting meeting with Alice Weidel, the leader of the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD). Elon Musk also promoted the AfD in the run up to the German election, following up a controversial post on X (“Only the AfD can save Germany”) with a livestreamed interview with Weidel. The AfD did not win the election, but its 21% was enough to secure second place (and the party’s best ever result). This is not to say the American interventions necessarily influenced the result one way or another—though it clearly illustrates MAGA’s willingness to discard international norms in support of its allies.

MAGA’s attempts to influence European elections did not stop in Germany. In Romania, the barred first-round candidate, Calin Georgescu, was replaced by George Simion—who styled himself as a Trump ally and featured on former Trump strategist Steve Bannon’s podcast. And, after a St Patrick’s Day meeting in the White House, Trump endorsed the mixed martial arts fighter Conor McGregor in his (now defunct) bid for Ireland’s ceremonial presidency. This shows how Trumpists can use even relatively small-time races to inject MAGA themes into Europe’s national debates.

In Poland, Trumpist interference may have been more consequential. During the country’s presidential campaigns in spring 2025, Trump welcomed nationalist candidate Karol Nawrocki to the White House and boosted him on social media. CPAC also held its first Poland edition in the run up to the election. There, the US secretary of homeland security, Kristi Noem, used a speech to tie future American military support explicitly to a favourable outcome for Nawrocki. The anointed candidate pipped centrist Rafal Trzaskowski by the narrowest of margins—fracturing Poland’s political leadership and giving MAGA an important foothold in Europe.

Trump and his acolytes have their eyes on more big prizes in the coming years. In Hungary, the 2026 parliamentary election threatens to unseat Viktor Orban, MAGA’s main European ally to date (and an important inspiration). In France, the 2027 presidential race is perhaps the ultimate scalp. Due to an embezzlement conviction, Le Pen is currently barred from running; the party’s other leader Jordan Bardella may take her place. Either way, Trump has signalled his support for RN, posting “Free Marine Le Pen!” on social media.

Step by step, and election by election, Trump’s America thus works to shift the ideological centre of gravity of European politics in MAGA’s direction.

Civilisational allies—and traitors

“Fundamentally, we are on the same team,” said Vance in his MSC speech. In so doing he cast Europe and America as parts of the same civilisation—which, in his view, likely gives Trumpists the right to correct the European path. This reflects a deeper assumption in Trump’s America: European politics are an extension of the US domestic scene.

This is not the way Trump’s America talks to Brazil or Japan. The difference is in how European and domestic politics intersect. In the past, US Democrats used Europe to delegitimise Trump at home—pointing to his unpopularity among Europeans, and holding up European policies on health and climate as models of sanity. Today, it is MAGA that weaponises Europe in America’s partisan struggle. In the Trumpist narrative, Europe’s mainstream parties—allied with US Democrats—are traitors to the West’s heritage. And this goes beyond partisan point-scoring. As Ivan Krastev notes, the struggle is about the very meaning of the West: whether it stand for a universal “free world”, as European liberals and American Democrats argue; or for a white and Christian civilisation, as MAGA and the European new right would have it.

The state department under Marco Rubio has been particularly active in the civilisational struggle. The department’s latest human rights report, published in August, spared Hungary despite the country’s persecution of LGBTQ+ communities. But it had no such mercy for Britain, France and Germany, criticising all three for their approach to free speech.

Staffer Samuel Samson went further. In a notorious post published on the department’s website, Samson accused the EU mainstream of betraying Western heritage and called for “civilisational allies in Europe”. The continent, he wrote, had become “a hotbed of digital censorship, mass migration, restrictions on religious freedom, and numerous other assaults on democratic self-governance.” He claimed this added up to “democratic backsliding”—which, according to him, affected American security and gave the US a reason to interfere. This was Vance’s MSC speech on steroids, mainlined and mainstreamed into the US federal bureaucracy. While the post was not signed by Trump or senior officials, it fit a clear pattern: portraying the European mainstream and the “global liberal project” as apostates who must be corrected or, preferably, expelled and replaced.

Part of Trumpists’ aim is to embed familiar new-right themes deeper into European politics. But it is also to impose a MAGA version of the West—and of democracy itself.

The free speech storyline

Free speech occupies a privileged position in the MAGA version of the West. Trumpists accuse liberals in the US and Europe of silencing dissent, aided by “deep state” institutions—the media, the bureaucracy, the judiciary—that have allegedly turned against ordinary citizens; they also denounce any laws to counter hate speech and harmful content as censorship.

The charges are riddled with contradictions. The Trump administration itself has sidelined critical journalists and defunded public broadcasters. At the time of writing, Trump is embroiled in his latest free-speech hypocrisy storm in the US, thanks to his alleged silencing of late-night talk show hosts such as Jimmy Kimmel and Stephen Colbert. Moreover, characters such as Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg are close to the administration, and their platforms—X and Meta, respectively—dominate Europe’s digital sphere, hinting at how Trumpist opposition to EU content moderation rules serves material US interests as much as ideological ones.

Regulating online speech and new technologies such as AI inevitably involves trade-offs. In principle this could be a policy debate in which the EU and the US strike their own balance differently, without hurling around accusations of illegitimacy. But free speech has become the weapon of choice for MAGA and the European new right in their assault on liberalism.

The European mainstream is partly to blame. In some countries, some laws related to speech appear to go too far (a law against “insulting politicians” in Germany, for example). MAGA and the new right exploit such perceptions of over-reach to broaden their appeal. In the US, friendly media eagerly quote examples from Europe as part of their domestic crusade (such as the arrest in the UK of Irish comedian Graham Linehan on suspicion of inciting violence against transgender people online). For voters in Europe who are otherwise uneasy about radical stances on migration or climate, a claim that “your voice is being silenced” may feel more accessible. Indeed, Patriots for Europe—a new political group in the European Parliament created by Le Pen, Orban and the like—cites the protection of free speech as one of its top priorities.

The emphasis on free speech brings two extra advantages to Trumpists in their culture war with Europe:

First, it allows MAGA to claim the mantle of the “free world”. After all, what could be more sacred than freedom of expression? Given that, it is easy to cast the European mainstream and US Democrats as the real censors for the simple fact they support some regulation of speech to protect other fundamental rights. The covid-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine heightened the mainstream’s appetite for fighting disinformation, which likely made parts of the EU’s societies more receptive to this charge.

Second, the free speech theme could help Trumpists connect with members of Europe’s new right who, knowing their own electorates, cannot present themselves as too close to the US president. In France, RN figures and billionaire businessman Vincent Bolloré’s sympathetic media empire have long zeroed in on “censorship”, with RN co-leader Jordan Bardella in February praising Trump’s “fight for free speech”. In the Netherlands, Geert Wilders, the leader of the radical right Party for Freedom, is receptive to such talk, not least after his own hate-speech conviction. What is more, research for this paper in the Czech Republic suggests the focus on free speech is strengthening the sense of a shared transatlantic cause among local far-right activists.

*

The three main storylines of the frontstage drama form a feedback loop. The free speech crusade shows how Trumpists turn a complex regulatory issue into a moral battlefield, amplifying the charge that Europe has betrayed the West’s heritage, and thereby justifying US interference in European politics. This is the clearest illustration of the ideological level of the culture war: a war of values, fought in Europe’s domestic arenas, framed as a Manichean clash over the very future of freedom and the West.

Backstage

But the frontstage action of Trumpists’ culture war with Europe is only part of the story. Backstage, a deeper contest unfolds—over Europe’s identity as an autonomous global actor and a peer in the transatlantic relationship. Here, Trump and his acolytes use their words and gestures to steadily undermine Europe’s sense of self. This symbolic battle over Europe’s identity—as well as its dignity and credibility—is the second level of the drama.

To be sure, Republicans in the US have long been dismissive of the EU. On some occasions, this even extended to Democrats: Barack Obama, for example, famously bailed on EU-US summits. What is striking about Trump’s America is that its characterisation of Europe no longer bears much relation to the idea most Europeans have of themselves. Previous editions of this series of papers have shown that the shocks of the past decade—from Brexit to the covid-19 pandemic to the war in Ukraine—have consolidated European sentiment. Now Trump risks pushing Europeans back to feeling weak and irrelevant.

Trumpists use material and cultural means to do so: policies and declarations, but also images, language and symbols that characterise Europe as inferior and unserious. It may look like Trump is just playing “hardball diplomacy” when he, say, threatens tariffs or hints at disregarding NATO’s Article 5. But the dual effect is to reinforce a storyline in which Europeans are subordinate and have no claim to agency. The same goes for when Trump dismisses the EU as an American foe, ridicules European leaders and bypasses EU institutions in favour of bilateral deals. If European leaders do not challenge this, then European citizens and politicians alike risk internalising the US narrative. It would then become a Gramscian “predominance by consent”—in other words, cultural subordination.

Scenes of humiliation

The July 2025 trade deal between the EU and the US illustrates this dynamic. Trump threatened the bloc with 30% tariffs on imports to the US, which pushed the European Commission to accept a 15% ceiling and pledge hundreds of billions of dollars in purchases from the US. Member states were divided: some leaders wanted Brussels to threaten retaliatory measures, but most preferred to avoid escalation. These divisions, and a general atmosphere of caution, helped nudge the commission into conformity. One European trade minister later described the deal as “the least bad alternative”, with many leaders echoing that sentiment.

And yet, the enduring image of the Scotland meeting was Ursula von der Leyen smiling beside Trump—a photo media critics described as symbolising a “humiliated Europe”. Paradoxically, the fact that the EU managed to get a better deal than most countries in the world (with India and Brazil, for example, facing a 50% tariff), may also have signalled to the European and global public that Europe is America’s vassal.

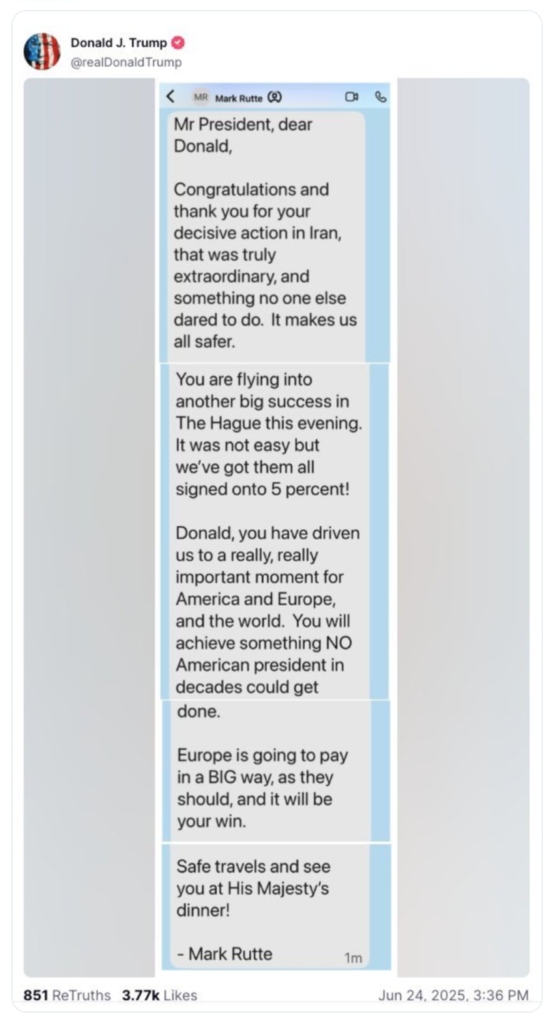

The NATO summit in the Hague served up another spectacle. The outcome, a pledge from all members of the alliance to work towards spending 5% of GDP on defence, pleased governments in France, Poland and the Baltic states. But the process was degrading. Leaked messages exposed the alliance’s secretary general, Mark Rutte, flattering Trump, which the US president gleefully shared online. The summit ended with Rutte jokingly calling Trump “daddy”, another headline moment that reinforced an of Europe as the obedient child.

The same script applies to Ukraine diplomacy. Europeans strive to be involved in negotiations to end the war. Trump, however, prefers to deal with Russia’s president Vladimir Putin bilaterally, and his administration treats European leaders as irritating extras rather than co-owners of the process and of the peace that might follow. Here too, the risk is not only to the substance of any deal. Again, the dual threat lies in the impression that filters through the media to the European and global public: Europe lacks agency and must accept whatever America imposes. (A third risk is that Europeans waste time and resources on “decorations” that have the singular purpose of placating the US president, such as reaching the spending 5% target, rather than on more consequential action, like finding ways to spend it wisely.)

Some European leaders openly express their disquiet at the humiliation. The French president, Emmanuel Macron, has been gathering supporters in his calls for strategic autonomy at least since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. But the return of Trump has added to their number. The German chancellor, Friedrich Merz, promised to seek “independence from the USA”, a country he considered “largely indifferent to the fate of Europe”. Italy’s president Sergio Mattarella has warned his European peers against “happy vassalisation”, urging the EU to choose between being protected and being a protagonist. And Spain’s president Pedro Sánchez has shown tactical skill with Trump. He secured an opt-out from the 5% defence spending pledge despite US and European pressure. And, in discussions on how to respond to America’s tariff threat, Spain was among the few countries advocating a tougher stance.

What is more, the Danish prime minister Mette Frederiksen has responded fiercely to Trump’s coveting of Greenland. And she has done so by emphasising the importance of European solidarity. By lucky coincidence, her country presides over the EU in the second half of 2025, which helps Frederiksen’s words resonate around Europe. The European Commission has also embraced some of this rhetoric. But, as discussed, its president seems to be too cautious to name the threat Trump poses to Europe.

The fawning response

Broadly, the prevailing attitude and the EU and national levels remains one of obedience. Many European leaders have taken the Rutte route and adopted flattery as strategy, likely aiming to appease Trump into less harmful attacks. Most others have kept a low profile—given practically every EU member state has some dependencies on the US.

Read more in the COUNTRY PROFILES.

In theory, this could buy the time the EU and European governments need to become independent from the US, particularly on defence. Economic chaos from a tariff war would hinder this process: as von der Leyen put it in her state of the union address: “Think of the repercussions of a full-fledged trade war with the US. Picture the chaos.” A similarly unhelpful outcome would result from a US withdrawal from NATO when Russia’s war in Ukraine is ongoing, and Kyiv’s reliance on European support is increasing. This is not to mention Russia’s drones creeping across EU borders.

But time is only bought if it is used and not wasted “limping along”. During any lulls in Europe’s subordination, European leaders will actually have to fill the gaps in the continent’s autonomy. Such lulls however often do not materialise from strategies of appeasement. It did not take long after the 15% tariff agreement for Trump to threaten more tariffs for any country or body (the EU and its member states included) that “discriminated” against US tech giants. Similarly, the 5% defence spending pledge does not seem to have reassured NATO’s most exposed members (the Baltic states, for instance) about the reliability of the US security guarantee. After all, Trump himself has done little to reassure them.

Finally, by dispensing with dignity and appeasing Trump, Europeans yet again cement their vassalisation in the eyes of the European and global public. They also undermine their own aspiration to serve as a beacon of rule of law in dark times: the trade deal, for example, may have looked in some ways like the EU accepted the principle of “might is right”.

Like Truman, Europe’s leaders too often behave as if they have accepted “the reality of the world with which they are presented”, instead of questioning it and offering a clearly defined alternative.

And we’re live

RADIO ANNOUNCER

Another glorious morning in Seahaven, folks…

(Andrew M. Niccol, 1998)

The two levels of the transatlantic culture war on their own tell only part of the story. The frontstage and backstage action combine to make a single reality, helping sustain a system in which the EU is stuck: reactive, fragmented and dependent.

On the one hand, the ideological battle over values feeds the deeper contest over identity. Trumpists’ support for the AfD in Germany or Nawrocki in Poland shifts national debates towards new-right frames. This further polarises European societies and fragments EU politics: when European leaders are absorbed by domestic divides—and some don MAGA caps—the EU becomes less able to emancipate itself from Trump’s humiliation. Poland, for example, was supposed to “be back” after Donald Tusk became prime minister at the end of 2023. But internal division and strife has helped the country once again fade away on the international stage. (There was no Polish representative at Trump’s post-Alaska summit meeting with European leaders, for instance.) In Germany, despite Merz’s goal for the EU to become independent from the US, the chancellor is constrained by a divided coalition and domestic competition with the AfD.

On the other hand, the struggle over identity and autonomy sets the scene for the ideological drama. When Europe looks small in its dealings with America, the US president can claim material and moral superiority in leading the MAGA version of the West. The mainstream then becomes defeatist and the post-liberal revolution looks irresistible. This further boosts the appeal of Trump’s European allies to voters—which prompts them to align even more with Trump. And the success of the US president in humiliating Europe’s mainstream, in embodying “the wind of change”, helps the European contingent make the case that they represent an avant-garde that was proven right.

*

Ideology and interests go hand in hand in this system, too.

Trump’s disdain for the EU seems at least partly ideological. He calls the union a project “formed to screw over the US” and has compared its bureaucracy to that of the Soviet Union. He also delights in ridiculing the EU’s “liberal” policies. At the EU-US trade deal announcement, he called wind turbines “ugly” and wind energy “a con job”—mocking Europe’s climate ambitions as foolish and vain. The lack of rebuke from a silent von der Leyen gave the impression of tacit approval of his rhetoric.

Think-tanks like the Heritage Foundation, meanwhile, echo and help shape these ideological themes, depicting the EU as elitist and “woke”. In contrast, they hail the likes of Orban, Le Pen and Wilders as fighting the liberal empire in “a pro-freedom alliance” (that also includes the leader of Italy’s League, Matteo Salvini, and Santiago Abascal, the president of Spain’s Vox). Most of all though, Trump and the MAGA movement see European liberals as allies of US Democrats, and thus as enemies. This all draws on an intellectual seam that ran through the fringe of the Republican Party for many years. Now, it has become mainstream thanks to the president himself.

But ideology also serves interests. When Trump and his acolytes undermine the EU’s image, this weakens the bloc’s hand in trade negotiations and, for example, in enforcing the 2022 Digital Services Act—the goal of which is to prevent illegal and harmful activities online. His opposition to Europe’s social media regulation also helps preserve the free for all that has proven so beneficial for his ideological allies on the continent. Moreover, his mocking of renewables bolsters the case for US gas exports. And the more the US chips away at EU unity, the more opportunities Trump gets to deal with Europeans bilaterally and not as a more powerful bloc. Still more division in the EU comes from the rise of the new right in key member states, helping Washington secure deals that favour US interests (for instance, the tariff agreement). Allies like Nawrocki, meanwhile, help oppose EU defence plans that would curb US arms sales; while Meloni softens the enforcement of EU rules related to X and Meta.

Trumpists’ ultimate interest seems straightforward: to perpetuate MAGA power at home. Europe helps them out here, too. Trump can present his extortion of material concessions abroad as bringing money into the US. He can also apply any loss of moral high ground among Europe’s mainstream to US Democrats. And, if Trumpists succeed in eliminating Europe as a serious contender to moral authority, they can then present America as the world’s only beacon of democracy.

Culture war thus serves realpolitik and realpolitik facilitates culture war.

Europe’s Truman moment

Truman continues to steer his wrecked sailboat towards the infinitely receding horizon. All is calm until we see the bow of the boat suddenly strike a huge, blue wall, knocking Truman off his feet.

(Andrew M. Niccol, 1998)

By uniting to stand up for their values and step out of America’s shadow, the EU and European countries can show they are not props on Trump’s soundstage, but autonomous actors in transatlantic and global politics. That would be the EU’s equivalent of Truman Burbank walking off set.

The good news is that conditions are ripe for them to do so. European sentiment is remarkably strong among the public. Almost all member state governments are still mainstream-led and pro-European—despite the rise of the new right, the polarisation Trump exploits and deepens, and MAGA’s allies and footholds in various member states. Still, there seems to be a leadership deficit at both the national and EU levels holding Europe back.

The societal surplus

Eurobarometer data shows European citizens’ trust in the EU is at its highest level since 2007. In 12 countries, it even increased between autumn 2024 and spring 2025 (most sharply in Sweden, France, Denmark, and Portugal).

In almost every member state, majorities feel attached to Europe and the EU, identify as EU citizens and are optimistic about its future. The exceptions—Cyprus, Czech Republic, France (despite the increase in trust) and Greece—have long been outliers. And, unlike the heady days of the Brexit culture wars, hardly anyone wants their country to leave the EU. This has likely contributed to the shift in most new right parties over the past few years to rhetoric about “changing the EU from within” (that is, watering it down in favour of national sovereignty).

The Eurobarometer polling also implies people see the EU as something much more important than just a common market. Majorities in all but three countries (Czech Republic, Poland and Romania) say that, in the future, the EU’s role in protecting European citizens against global crises and security risks should become more important. In all 27 member states, majorities believe the EU’s voice counts in the world—suggesting people have not yet internalised Trump’s humiliations and have confidence in the bloc’s international role.

Similarly, ECFR polling in May 2025 revealed widespread support for greater defence spending and developing an alternative to the US nuclear deterrent. It showed overwhelming public backing too for Europe not to follow the US if Trump tried to impose a settlement on Ukraine, withdraw military support for the country, or lift sanctions on Russia. That poll also found people increasingly see Europe and America as standing for two very different models of democracy. Those electorates who see the US political system as working well, tend to say the EU is broken. Conversely, those who think America has gone astray tend to view the EU as functional model.

The crises of the past decade have seemingly shown many Europeans the importance of collective action in a volatile world. Now, the early days of Trump’s culture war appear to have helped turbocharge this view, clarifying the values people want the EU to embody and strengthening the case for strategic autonomy.

But the picture is not uniform across the EU27. In some countries—especially in Cyprus, Czech Republic, Greece and Slovenia—distrust in the EU remains high. The increasing trust in the EU in some places (particularly in northern Europe) contrasts with increasing distrust in parts of the rest (like Greece, Italy and Romania).

Moreover, attitudes towards the EU have become dividing lines in some countries’ domestic culture wars. Many of these are member states in central and eastern Europe. For example, the EU got sucked into the debate in the Polish and Romanian elections. The same is happening ahead of the Czech Republic’s election in October, and as Hungary prepares to go to the polls next year. The EU has also become divisive in Bulgaria and Slovakia, as the former prepares to join the euro zone in 2026 and given the latter’s prime minister Robert Fico gleefully uses the bloc as a scapegoat. The fact that some of these countries also have problems with media freedom exacerbates the vulnerability of their European sentiment and exposes it to external influence.

Yet, overall, societies are showing many signs of being ready to escape. The question is whether Europe’s politicians will be able to lead.

The leadership limbo

Research for this study confirms most of the EU’s governments remain mainstream-led and pro-European. Eurosceptic breakthroughs came close but did not materialise in the Romanian presidential and legislative elections. The same goes for Austria’s legislative election in September 2024, which the far-right won but was kept out of government by a cordon sanitaire of mainstream parties. A far-right Eurosceptic party left government in the Netherlands, prompting a snap election that will take place in October. Eurosceptic parties are coalition partners in Croatia and Finland, but their influence in government is limited.

There are, of course, some shadows in this picture. Orban’s Hungary is MAGA’s main stronghold in Europe and is openly hostile to the EU. Meloni and Fico mix Eurosceptic rhetoric at home with pragmatism in Brussels. They may soon be joined in their selective Euroscepticism by the Czech Republic if Andrej Babis wins; and in a Trumpian orientation by Slovenia, should Janez Jansa win the legislative election there in 2026. But, for the first time since 2010, a win for Orban in the Hungarian election is not guaranteed. What is more, having to deal with Orban, Fico and Meloni in the European Council has not stopped the EU maintaining its strong support for Ukraine; nor has it stopped the bloc maintaining sanctions against Russia, or drastically reducing its reliance on Russian fossil fuels.

Still, Trump’s culture war is testing the EU’s resilience. Too many governments are reluctant to confront the US directly on issues of trade, technology, values and multilateralism. Bolder voices, such as those of Macron, Frederiksen and Mattarella, are isolated. The mainstream often looks adrift, tempted to imitate the new right rather than challenge it (like the centrist frontrunner and an eventual loser in Poland’s presidential election, Rafal Trzaskowski). European institutions—notably the European Commission—struggle to fill that leadership gap.

Another feedback loop

Leaders face three main barriers to overcoming their inaction.

- The dark side of the polls.

A clear public appetite exists for greater European autonomy. But many European citizens doubt the EU’s capacity to make things happen. The polls often also reflect the divided societies within member states.

ECFR’s May 2024 polling found that most people in most countries believe it is impossible for the EU to become independent from the US for its security; Denmark was the only country in which a majority thought the EU could compete economically with the US and China. Leaders should not take such scepticism as a cue for inaction. Indeed, the scepticism may reflect a belief that politicians will not do anything anyway. Some national leaders also might find public scepticism about the EU’s capacities convenient—as this allows them to insist on maintaining national competences in key areas rather than pooling them together.

Moreover, citizens are often divided on the right course of action vis-a-vis Trump’s America—and highly polarised on the EU. This makes a more assertive stance a risky political bet. The European Commission, meanwhile, has to deal with the divergent perspectives that dominate in 27 member states. One survey from Le Grand Continent, for example, found that almost half of the French public would want the EU to “oppose” the US government; in Poland that figure was just 18%. With Europe so cacophonous, it may seem easier to kick the can down the round than to offer bold leadership that would provoke an uproar.

- It doesn’t seem that bad—and will all be over soon.

ECFR’s May 2025 polling found EU citizens were quite relaxed about the future of the transatlantic alliance. The dominant view was that Trump had damaged relations but that they would improve once he leaves office. That polling also found most Europeans believed a working relationship with Trump’s America was possible, allowing Europeans to avert a trade war, maintain US troops in Europe, and keep the American nuclear umbrella in place.

This suggests citizens and governments alike are comfortable ignoring what is happening backstage. It is hard to leave the zone of “appease and delay”, especially as research for this paper found most governments are aware of their countries’ real and imagined dependence on the US in trade, investment, energy, technology, weapons and troops.

- Nothing is more dangerous than unmet expectations.

Another paradox of this moment is that growing European appreciation for collective action and the Europe’s normative role comes with demands.

This puts national and EU leaders—and the European Commission in particular—in an impossible position. Many national governments (such as in France, Germany and Poland) are too weakened by the rise of the new right at home to meet citizens expectations. The EU also struggles to do so under its current decision-making structures. It is easiest for people and their governments to blame Brussels.

Research for this paper found that in several countries—including France, Ireland, Malta and Spain—the EU’s credibility has suffered from public perceptions of inaction over Israel’s war in Gaza. In Hungary, strongly pro-European voters were upset when Brussels did not react swiftly enough to the government’s ban of the Budapest pride parade. Some rule-of-law sensitive Europhile politicos were appalled that the European Commission would not undertake a serious debate about transparency when Ursula von der Leyen faced a no-confidence vote in July. The more environmentally oriented parts of the European electorate deplore the bloc’s shift away from the green agenda and towards competitiveness. Member states becoming increasingly hardline on migration is nothing new to defenders of human rights; but it is different story when this is normalised at the EU level as the 2024 Pact on Migration and Asylum.

It is unfair to put all the burden on Brussels. Nevertheless, the message to many citizens is one of Europe falling short of its promises and compromising on its ideals—and, in this sense, proving its incapacity to lead. This does not provide a strong foundation for more assertive European action in the areas of trade, defence and foreign policy.

*

The three obstacles reinforce one another: doubts and cynicism feed inertia, inertia deepens disappointment, and disappointment fuels more doubts. Together they create another feedback loop that helps do Trump’s work for him—keeping Europe’s leaders in a cautious and reactive state. The centrifuge holds them inside their Truman Show. Leaders stare at the painted sky, uneasy with the artificial world around them—still reluctant to step through the door that could lead to the authorship of their own story.

The way out

CHRISTOF

You can leave if you want. I won’t try to stop you. But you won’t survive out there. You don’t know what to do, where to go.

(Andrew M. Niccol, 1998)

In “The Truman Show” a campaign of subliminal messaging aims to blunt Truman’s curiosity about what is out there. Headlines like “Who needs Europe!” depict everywhere except Seahaven, the Christof-controlled realm, as “less than”—as irrelevant and undesirable. The film thus uses the idea of “Europe” to keep the show on the road and Truman pliant and obedient.

And so it is with Trump. Trump excludes European leaders from Ukraine talks and treats the EU as a client to extort. His acolytes, meanwhile, help him cast the EU’s mainstream parties as civilisational foes. The goal may well be to create a “happy vassal”: a Europe that is too weak and dependent to act on its own.

But Trumpists succeed in their culture war because they exploit real vulnerabilities. They take advantage of the EU’s dependence on the US for defence, trade, technology and energy. They also use the bloc’s failure to live up to its own ideals, as well as the polarisation in societies that forms loopholes in European sentiment. The EU’s cacophonous power structure inhibits a bold, quick response. Vance’s MSC speech struck a nerve precisely because it highlighted some of these real weaknesses.

There is no simple answer. European leaders face conflicting pressures. But once they accept this is all part of the culture war—and the target is “Europe”—they will find a few new options open up.

Liberals: Defend liberal values

Mainstream parties must regain confidence in Europe and find the courage to defend its values. Too often the rise of the new right prompts them to drift towards them in hope of keeping voters. But in doing so they demobilise their base and legitimise a slide into xenophobia, intolerance and contempt for the rule of law. This drift weakens the EU’s global image as vital to protecting liberal democracy.

Such conformism will not cut it. Liberals face a coordinated international movement determined to overturn Europe’s liberal democratic order. But the strength of European sentiment across most of the EU means they can win voters back by making that case clearly. Destabilising as it is, Trump’s return offers them a foil—a mirror that highlights the appeal of a confident, pro-European alternative.

European liberals should not hesitate to reappropriate contested concepts such as sovereignty, nationalism and patriotism, and set out how these can strengthen the EU rather than undermine it. They should frame this in terms of pride, confidence and optimism—not the shame, fear and declinism that Trumpists exploit. But in so doing they must continue the work I recommended last year: unclogging channels of participation in Europe so politics reflects its increasingly diverse electorate, and the idea of “Europe” becomes less old, white and western European.

National leaders: Stop mistaking flattery for strategy

National leaders need to abandon the strategy of “flatter, appease, distract” towards Trump. It is flawed and short-sighted. They instead need to be assertive and show a willingness to take greater responsibility for Europe’s security. To do so, they need to invest in building up European strengths: in defence and technology, but also the continent’s partnerships with countries and regions around the world.

European leaders’ timidity was clearest in their response to Trump’s trade war. The EU has tools to resist economic coercion. But too few member states were ready to use them, which undermined the European Commission’s position. Leaders seem to understand that defence, trade and digital policy form a multidimensional chessboard where one move provokes another. Less visible is that every concession on policy plays into the culture war, feeding an image of European weakness.

There is no reason why Europe’s “summer of humiliation” should have to turn into a “century”. If European leaders get their acts together, Europe can thrive. Trump has accelerated the destabilisation of the world order and created new threats. But lurking underneath all this are genuine opportunities.

The alternative to humiliation is strategic autonomy. The EU and European leaders need to make this happen step by step in defence, technology, energy and completion of the single market. They should do all this even if it means sharper transatlantic tensions. Occasionally, Europeans may need to buy time, for instance to keep American troops in the EU. But they must balance such concessions with redoubled efforts elsewhere: building coalitions to support Ukraine, defending free trade and global health, undertaking the long-overdue economic reforms, and showing engaged leadership in their neighbourhood—from the Balkans to Gaza. Leaders also need to project an image of confidence and integrity, not vassalage.

But all this requires unity. Such unity should be among all 27 member states when possible and as coalitions of the willing when necessary. The governments of some countries in particular—Germany, Poland, Sweden—should step out of the shadows and provide the leadership that is so often missing. This would encourage other member states to do the same.

Read more in the COUNTRY PROFILES.

It is unfair to leave that job only to Macron and Frederiksen, just as it is too easy—and damaging—to use von der Leyen as a lightning rod for public discontent. This is especially the case now polls indicate that majorities in France, Spain, Germany and Italy found the tariff deal humiliating, and want von der Leyen out. Leaders across the EU should stop blaming Brussels for the EU’s problems. Instead, they need to explain to their citizens that only the EU provides the framework for the prosperity and freedom of their countries amid increasing threats and an unreliable US.

The EU: Become a director in the show

The European Commission needs to assume a leadership role in fighting the transatlantic culture war.

The commission should use its existing instruments with conviction. It should use its trade competences to counter coercion and to expand the EU’s network of partners around the world. It should also deploy the Digital Services Act (DSA) to defend the EU’s vision of free speech. One promising example is the European Commission’s decision in September to sanction Google: this was in keeping with the bloc’s digital regulations, and the commission took its decision despite the risk of provoking Trump. Another is the EU’s ambitious schedule of free trade negotiations with partners around the world (including India). But Brussels will need to remain committed to these efforts even when it meets resistance from Washington (for instance on the DSA) and member states (for instance on the Mercosur deal).

The European Commission—and its president in particular—also need to pay more attention to symbolism. Rather than its meek silence to date, the commission needs to defend European values when US officials misrepresent them.

Brussels should also expand its range of initiatives to fight the culture war.

Initiatives such as the proposed “European Democracy Shield” or the forthcoming “EU Civil Society Strategy” respond to genuine public demand for Europe to defend democracy, not just manage markets; as is also the case with the increased EU funding for independent media von der Leyen mentioned in her state of the union address. These should all prove useful in preserving strong European sentiment in member states where it is most vulnerable.

But such initiatives have to come with real funding, credible enforcement and safeguards against misuse. Mishandled, they could backfire—reinforcing far-right claims that Brussels itself is the foreign meddler in national politics. Without a renewal of Europe’s liberal mainstream, such initiatives also risk proving the point of critics who say elites notice the speck in the new right’s eye while ignoring the log in their own. The EU should also be mindful not create a false impression that Europe’s public—rather than its leadership—is the greatest hindrance to sustaining strong European sentiment.

The commission’s Culture Compass strategy is promising. To be launched by the end of 2025, this initiative is an opportunity to acknowledge (including through serious funding and smart programming in the next seven-year budget) the crucial role the cultural and creative sectors play in keeping Europeans together. But its purpose could be more ambitious than that. The initiative should offer Brussels a new framing to talk about Europe in terms that are closer to people’s hearts than the abstract and anodyne “competitiveness”. The moment is ripe to treat culture as the EU’s key geopolitical asset. This is relevant to the challenge of enlargement as well as fighting Europe’s culture war with Trump’s America.

New right: Don’t become the happiest vassals of all

Even Europe’s new right should take note. It may sound paradoxical to urge parties allied with Trump to rally around the EU. But the culture war MAGA is waging is about more than values—it is about Europe’s identity and agency.

If Trumpists succeed, the US will find it easier to impose tariffs, dilute security guarantees and cut deals with Russia over Europe’s head. This may not trouble the AfD in Germany. But it should concern Meloni in Italy or Le Pen in France, the former as prime minister and the latter aspiring to become president. Even for the new right, the EU is the only framework in which leaders can protect their countries’ sovereignty and prosperity.

The end—or a new beginning

He steps through the door and is gone. Silence.

(Andrew M. Niccol, 1998)

“The Truman Show” was a product of its times. It embodied the late 20th century liberal-humanist ethos: the idea that an ordinary person can uncover the artificiality of imposed structures and strive for freedom. The film also presumed that truth, autonomy and dignity are universal aspirations worth risking one’s comfort for.

A Trumpist Hollywood would never make such a film. The MAGA message is that safety lies in closing doors and reaffirming old identities; “The Truman Show” is the exact opposite—with its themes of resisting authority, breaking illusions and walking into the unknown. It would not portray Truman as a victim breaking free, but as a dangerous element. His independence would be written as ungratefulness for the security and comfort the show provides. This is not to mention what a bad example such a free spirit would set for the film’s audience. But it is precisely the spirit of “The Truman Show” that Europe must now embody: the courage to leave the comfort of a scripted reality and decide its own future.

If the EU asked Truman Burbank for advice he would probably say: leave the soundstage, no need to destroy it, and embrace the unknown. The recommendations in this paper could map onto this advice. But Truman’s hypothetical words also help in imagining what a victory for Europe in the transatlantic culture war might look like.

For one, Trump’s America would have less space to drag Europe into ideological battles—because a re-energised mainstream would have blunted the appeal of Trump’s European allies. It would also mean a more resilient European market, stronger defence capabilities and bolder leadership would make the continent more autonomous in the world. Europe would also have reasserted its attachment to its values, correcting course to show people around the world that it lives them through deeds as well as words—using its ingenuity and coalition-building skills to defend multilateralism.

Ultimately, such strength and independence would mean the EU and European countries had a better chance of preserving a strong transatlantic bond—but as peers, not vassals; as authors of their own story yet to be written.

Country profiles

No EU member state is exempt from Europe’s culture war with Trump’s America; each of the 27 countries simply has different role on the soundstage:

The director’s crew are countries actively producing Europe’s “Truman Show”. Governments in these states amplify MAGA narratives, reinforcing American influence in the EU. Hungary under prime minister Viktor Orban is MAGA’s stronghold in Europe. Trumpists also have footholds in Italy and Slovakia, under their respective prime ministers Giorgia Meloni and Robert Fico.

The most common role for member states is that ofa tempter. These countries offer Europe comfort, status and belonging, which lures our protagonist into staying in the illusion. They normalise the Trumpian script in the EU either through domestic MAGA-style activism from forces outside government (Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Spain), through a culture of humility towards America in government (Finland, Greece, Ireland, Sweden), or both (Netherlands, Portugal, Romania).

The prophets play the reverse role. These countries reveal the truth and urge the protagonist to break free. The EU only has one real prophet so far: Denmark. There, leaders advocate for strategic autonomy and insist Europe does not have to follow Trump’s script. (Sweden and Finland have the greatest potential to join Denmark in this role.)

The extras make up most of the remaining cast. These countries are present on set but do not drive the plot. Even when they host MAGA-like ideological battles (Bulgaria, Slovenia) or display diffidence vis-a-vis the US (Bulgaria, Croatia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania), they lack the influence of the tempters. And even when they are strongly pro-European (like Luxembourg), they lack the firepower to be prophets. Sometimes extras seem not even to be present on set (Cyprus, Malta).

The door-holders are the countries whose choices could determine the arc of the EU’s story. This role belongs to Germany, France and Poland: because of their political weight, but also because each could tilt towards the prophets or join the director’s crew. In Germany, Chancellor Friedrich Merz argues for independence from the US. But his divided coalition and the surging far-right Alternative for Germany confront him with sharply different futures. France under President Emmanuel Macron rivals Denmark in championing strategic autonomy; a far-right presidential victory in 2027 (or sooner), however, could bring Paris into Trump’s orbit. In Poland, the next legislative election is due in 2027 (or earlier). The result of this could decide whether MAGA’s foothold turns into a stronghold, or whether Poland once again—like in 2023—might become a laboratory of resistance to the new right.

Methodology

To understand European sentiment in 2025 and how it may evolve in the years to come, the European Council on Foreign Relations and the European Cultural Foundation oversaw a study across the EU. In their respective EU member state, ECFR’s network of 27 associate researchers investigated their governments’ and citizens’ attitudes towards Europe, paying particular attention to how and whether these have interrelated with Donald Trump’s return to the White House. The researchers conducted interviews with relevant policymakers and policy experts and drew on opinion polls and other sources, and in July 2025 they completed a standardised survey. This allows the comparison of the 27 member states on three major issues:

- The broader evolution of attitudes towards Europe on the part of EU27 governments and citizens;

- The extent to which Donald Trump’s re-election has an impact on politics in EU member states;

- Perceptions of Europe’s performance in the second Trumpian age.

European sentiment

In using the concept of the “European sentiment”, we have been inspired by the works of Swiss philosopher and founder of the European Cultural Foundation, Denis de Rougemont, who – in the aftermath of the second world war – wrote about the need to awaken a “common sentiment of the European.”

In the first edition of the European Sentiment Compass, we elaborated on the way this concept could be operationalised for the analysis of today’s Europe. The working definition of European sentiment used in this paper understands it as a sense of belonging to a common space, sharing a common future, and subscribing to common values – which is best observed against the background of major shocks and events.

About the author

Pawel Zerka is a senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations. As lead analyst on public opinion, he spearheads the organisation’s polling and data research on foreign affairs. His other areas of study include global trade policy, Latin American politics, and Poland’s and France’s role in the EU.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the European Cultural Foundation (ECF)—especially André Wilkens, Isabelle Schwarz, and Tsveta Andreeva—for their relentless interest and support in exploring the nexus between culture and foreign policy, and for their confidence in developing the European Sentiment Compass as a joint ECFR-ECF partnership and initiative.

This project is largely based on research conducted by ECFR’s 27 associate researchers, whose hard work needs to be recognised. They are: Sofia Maria Satanakis (Austria), Vincent Gabriel (Belgium), Marin Lessenski (Bulgaria), Robin-Ivan Capar (Croatia), Hüseyin Silman (Cyprus), Vladimir Bartovic (Czech Republic), Christine Nissen (Denmark), Viljar Veebel (Estonia), Tuomas Isu-Marko (Finland), Zélie Fourquier (France), Stephan Naumann (Germany), George Tzogopoulos (Greece), Zsuzsanna Végh (Hungary), Harry Higgins (Ireland), Alberto Rizzi (Italy), Kārlis Bukovskis (Latvia), Justinas Mickus (Lithuania), Tara Lipovina (Luxembourg), Daniel Mainwaring (Malta), Niels van Willigen (Netherlands), Adam Balcer (Poland), Lívia Franco (Portugal), Oana Popescu-Zamfir (Romania), Matej Navrátil (Slovakia), Marko Lovec (Slovenia), Astrid Portero (Spain), and Nicholas Aylott (Sweden).

A paper of this volume is inevitably the result of a teamwork. It would be hard to overstate the contribution of Kim Butson who demonstrated incredible patience, meticulousness and ingenuity as editor. Early exchanges with Jeremy Shapiro and Zsuzsanna Vegh encouraged the author to look at Europe’s relations with Trump’s America through the prism of a “culture war”. Adam Harrison and Jeremy Cliffe provided sage advice. Celia Belin, Rafael Loss and Jeremy Shapiro gave crucial feedback on the first, very imperfect draft. Gosia Piaskowska was of great help in ensuring smooth cooperation with ECFR’s associate researchers. Special thanks go to Chris Eichberger for graphic design, Nastassia Zenovich for data visualisations, Martin Tenev for his brilliant web design, Andreas Bock for managing the communication side of the project, and Nele Anders for leading on the advocacy side. Finally, the author wouldn’t get very far without the trust of Susi Dennison and Anna Kuchenbecker who have supported this project since its inception in 2021.

Any mistakes or omissions are the fault of the director alone.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.