The port in Port Sudan, on Oct. 28, is the main point of entry for weapons and ammunition supplying the Sudanese Armed Forces.

Millions of dollars worth of weapons, fuel and drones flowing through Port Sudan have given the country’s army the upper hand in the world’s deadliest war, as Tehran and Moscow jockey for military bases on the Red Sea.

By Simon Marks and Mohammed Alamin

Photography by Eduardo Soteras for Bloomberg

Rocket launchers, bullets and handguns line the walls of Dirar Ahmed Dirar’s cramped office in Port Sudan’s Daim Almadina neighborhood. Ammunition belts for Russian-made machine guns hang from his secretary’s desk, and Chinese assault rifles lie stacked on chairs.

Toying with a pair of live hand grenades, the Sudanese militia leader described how the national army’s foreign backers helped turn the tide in the brutal 20-month civil war that’s sparked the world’s biggest displacement crisis, sent millions hurtling toward famine and left the mineral-rich country of 50 million people in ruins. Soldiers on both sides of the war have indiscriminately killed civilians and prevented food aid from reaching vulnerable populations.

“Sudan has support from Iran and Russia,” said Dirar, a senior member of Sudan’s Beja tribe, who commands a motley crew of pro-army militiamen and sits on a military committee backing the Sudanese army. “They provide different things like drones and weapons. So now the balance of power has changed.”

Proxy Supplies Via Port Sudan Are Proving Pivotal for Sudan’s Army

Government Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) were regaining areas of control from the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) as of Dec. 14, 2024

Note: *The Darfur Joint Forces (Minnawi and Ibrahim). South Sudan People’s Defense Forces (SSPDF) control of southern Abyei not shown Sources: Thomas van Linge; Natural Earth

The war — fought between two generals jockeying for control of a vast country with a strategic 530-mile Red Sea shoreline — is the bloodiest example of an anti-democratic wave that’s swept Africa’s Sahel region in recent years. Coups from coast to coast have seen military juntas move away from Western allies and closer to Russia — which has deployed mercenaries to Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger and the Central African Republic. None have drawn in as many external actors as Sudan—and in contrast to their recent humiliation in Syria, Russia and Iran are currently on the winning side.

“Sudan seems to be an easy win that you can get on the cheap,” said Magdi el-Gizouli, a Sudanese academic and a fellow of the Rift Valley Institute. “You can get the Red Sea coast, you can get political influence in Khartoum, you can get mineral resources at a very cheap price. You can make a hell of a profit out of a country like Sudan.”

As the war drags on, Russia has sold the army millions of barrels of fuel, and thousands of weapons and jet components, while Iran has sent shipments of arms and dozens of drones – allowing the military to recapture parts of the capital, Khartoum, and wide swathes of territory across the country from its rival, the Rapid Support Forces paramilitary group. The army’s arsenal has grown so much that earlier this year it built a new hangar at the military wing of Port Sudan’s airport.

The influx of weapons means the war is increasingly being fought in the air. Early on Nov. 21, the army used anti-aircraft weapons to shoot down a barrage of RSF drones near the cities of Atbara and Ad Damar, according to a United Nations security assessment seen by Bloomberg. “Both sides are actively replenishing their weapon supplies, including drones, to strengthen their positions,” according to the report.

Both Russia and Iran have held talks in recent months with the army to build military bases in Port Sudan, according to two Sudanese intelligence officials and four Western officials. Those discussions have gained significance as Russia risks having its main airbridge to Africa severed by the potential loss of two bases in Syria after the ouster of Bashar al-Assad, and as Iran finds itself weakened by Israel’s sustained attacks on its proxy force Hezbollah in Lebanon.

Meanwhile, the United Arab Emirates has acted as the main supporter of the RSF, according to the US and UN investigators — charges the UAE has repeatedly denied. Both sides have paid for their arms using proceeds from Sudan’s gold sector, which generates more than $1 billion a year for the army alone.

Though the Chinese government hasn’t picked a side – Chinese-made drones have been used by both parties – Beijing has built a $140 million harbor in Port Sudan that ships camels eastward, and is in talks with the army to invest in a new oil refinery and rehabilitate the country’s largest slaughterhouse.

“We are very grateful to our friends and appreciate the help we have received,” Malik Agar, deputy to army leader General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, said in an interview in Port Sudan, without identifying specific countries. “We know who our friends are and who has chosen not to back us.”

The Military Wing of Port Sudan International Airport Has Expanded

Satellite imagery shows the construction of new hangers and tarmac in 2024

Source: Planet Labs

The RSF, which UN investigators have said the UAE is arming through a remote airbase in neighboring Chad, has used illicit networks to import weapons, drones and armored personnel carriers, according to two regional security officers and a June report by Amnesty International. Libyan military leader Khalifa Haftar has also supplied the militia with fuel and other material, according to a Sudanese intelligence official and two Western security officials.

The army has also purchased an unknown number of Turkish Bayraktar TB2 drones, two Western security officials said. Private arms companies from Serbia, the UAE and Russia have also exported arms into Sudan in violation of a UN arms embargo covering the Darfur region, according to Amnesty. Meanwhile, Egyptian military officials are also advising Sudan’s army, a Sudanese security official and two foreign security officials said, and last month the Egyptian ambassador to the EU made a plea to Brussels not to sanction the army, according to a diplomatic cable seen by Bloomberg. Multiple requests for comment sent to the Egyptian embassy in Brussels wasn’t returned.

“The most important ambassadors today in Port Sudan are the Russian, the Turkish, the Egyptian and the Iranian,” said el-Gizouli of the Rift Valley Institute. “Nobody in Sudan can fight without external support — it’s just not possible. You don’t make enough weapons in Sudan. You don’t make enough ammunition. You don’t generate fuel.”

Dirar Ahmed Dirar, head of the Eastern Sudan Parties and Armed Movements Alliance, at his office in Port Sudan. The Beja are a tribal group from Eastern Sudan, training thousand of militia men to support the Sudanese army.

A member of the Sudanese Armed Forces with a captured projectile, intended to be used with a drone, in the city of Omdurman, Sudan, on June 18.

The flight controller of a captured drone in Omdurman.

On the roads surrounding the harbor in Port Sudan, hundreds of Beja laborers unload trucks laden with goods into humid warehouses. But from time to time, Sudan’s military intelligence cordons off access to the southern terminal, where cargo shipments carrying weapons arrive, according to two port officials who asked not to be identified for fear of government retaliation.

Two miles away at The Dock – an air-conditioned restaurant in an art-deco building – the countries shipping those weapons in are on full display, with Russian military advisers dining next to officials from China, Turkey or Iran, paying for local seafood with thick bundles of local currency.

They’ve been coming to The Dock ever since war broke out April 2023, after the country’s two most powerful generals – al-Burhan and RSF leader Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo – failed to forge a power-sharing deal. Following a popular revolt that overthrew Islamist dictator Omar al-Bashir in 2019, the two ousted a Western-backed civilian-led government in a 2021 coup, killed young protesters in the street and stymied pro-democracy efforts before falling out.

As the two forces battled across the country – displacing 11 million people and killing at least 150,000 more – foreign powers swooped in to back either side.

Bales of cotton being transported into a commercial warehouse. Military intelligence often cordons off access to the port to offload weapons destined for newly recruited soldiers.

A man resting near a rail yard. The rail network is being used by the military government to deliver goods and supplies to parts of the country under its control.

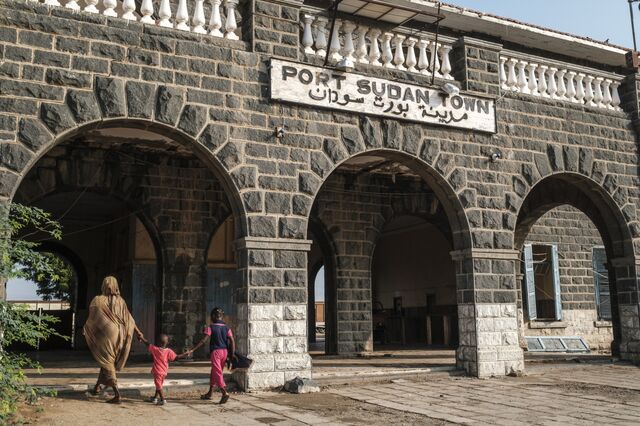

A woman and children enter the city’s train station. Sudan has the second longest railway lines in Africa, but it partially stopped working after the eruption of the war.

Most of the international pressure – including at the UN Security Council – has focused on UAE support for the RSF, which is driven by its longtime opposition to political Islam given the army’s ties to Islamists, according to US and EU officials. Little attention has been paid to the role of Russia, which after years of supporting the RSF via the Wagner Group – the Kremlin-linked mercenary company – shifted its allegiance to the army at the beginning of this year. Its engagement in Sudan’s war in many ways goes far beyond its use of proxy forces like Wagner in other African countries.

Shortly after Sudan’s deputy leader Agar traveled to Russia in June for talks on acquiring weapons in exchange for letting the Kremlin open a military fueling station on the Red Sea, arms shipments began, according to the two port officials, who witnessed several deliveries in recent months.

Russia has also provided intelligence support to the army, said a Sudanese intelligence official and two foreign security officials who asked not to be identified discussing matters that aren’t public.

“Russia wants money and a naval base on the Red Sea — aligning with the army means arms sales and a potential facility in Port Sudan,” said Justin Lynch, a researcher with Conflict Observatory, a US government-funded group monitoring the wars in Sudan and Ukraine.

That’s meant ramping up fuel shipments to the army this year. Following seven months in which it exported no fuel to Sudan, Russia delivered 2.8 million barrels of diesel and gasoline between April and October, accounting for 47% of all of Sudan’s imports. Since March, at least 12 tankers coming from Primorsk, Tuapse, Vysotsk, Ust-Luga and St. Petersburg in Russia — 10 of which have unknown owners — have docked in Port Sudan. In late November, officials from Sudan’s Energy Ministry held talks with executives from Gazprom about repairing damaged oil infrastructure, developing existing oil blocks and building a new pipeline and refinery in Port Sudan, the ministry said in a statement.

Russian Oil Imports to Sudan Are Increasing

Sudan’s total imports of refined products by sea

Note: Quantities measured in barrels Source: Vortexa

Russia also offered Sudan an S-400 surface-to-air missile defense system as part of the deal for a military base, a Sudanese intelligence official said. Sudan, however, hasn’t accepted the offer for fear they might alienate the US and other Western powers, the Sudanese intelligence official and two US officials said.

Agar declined to comment on the role of foreign powers in the war. The Russian Embassy in Port Sudan and its foreign ministry didn’t reply to several requests for comment.

Weapons entering the port have helped the army re-capture parts of the capital Khartoum and large swathes of territory in central Sudan.

But residents in the city suffer from crippling inflation and an influx of displaced people that are placing pressure on basic infrastructure such as roads and sewage facilities.

At the city’s main market, business owners said they’ve been confronted by a deluge of needy families displaced from conflict elsewhere in the country seeking refuge.

The price of basic items such as bread have increased fivefold since the beginning of the war in April 2023.

As the war escalated, Iran, which re-established diplomatic ties with Sudan in late 2023 after a seven-year hiatus, dispatched diplomatic officials to Port Sudan and opened an embassy.

The regimes in Tehran and Khartoum were close for much of the past three decades, united by political Islam after Bashir seized power in 1989, and it helped his government establish its intelligence service. But that relationship soured around 2015 when Sudan tilted toward regional giant Saudi Arabia and sent troops to help fight against Yemen’s Iran-backed Houthis.

Now, Tehran is actively supplying weapons and drones to the army, according to intelligence officials and diplomats, along with satellite images and pictures of weapons on the battlefield. Iran’s foreign ministry and mission to the UN didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment.

In January, RSF soldiers shot down a drone near Khartoum that was modeled after Iran’s Ababil aircraft – locally made with Iran-sourced parts, according to Wim Zwijnenburg, a weapons expert and project leader of humanitarian disarmament at PAX, a Dutch pro-peace organization. He analyzed and geo-located videos of the drone posted online by RSF fighters celebrating in the capital.

He also identified a Mohajer-6 – a combat drone manufactured in Iran by Quds Air Industries that carries precision-guided munitions – on the Wadi Sayyidna air base near Khartoum in January. Satellite images from May show a new hangar and several storage facilities were constructed at the military wing of the airport in Port Sudan.

Iranian Cargo Planes Flew to Sudan at Least Three Times in 2024

Recorded Iranian Boeing 747 cargo flight routes from Tehran Airport for Port Sudan International Airport on July 14, and from Bandar Abbas Airport on May 18 and June 12 2024

Source: FlightRadar

Between January and July this year at least seven flights operated by Qeshm Fars Air, a US-sanctioned airline with ties to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ elite Quds Force unit, traveled between Tehran and Port Sudan, according to flight-tracking data. No such flights were recorded during 2023. Four of the seven flights ended their journey in Tehran at the Islamic Republic of Iran Air Force apron of the Mehrabad Airport, according to the Conflict Observatory.

“Iran sees Sudan as one of the few markets for weapons sales,” said Lynch, the researcher at the Conflict Observatory. Russia is also a buyer.

The army has funded its war effort by reviving the formal gold sector that crashed when the conflict broke out.

Last May, the state-owned Sudanese Mineral Resource Co., which regulates the mining sector, slashed taxes on imports and fuel, and provided cash to companies to help with logistics, said Alsadig Alhaj, head of the SMRC’s planning department. It also cut fees for artisanal miners, leading to a drop in smuggling and a rise in gold sales to the government. The turnaround coincided with global gold prices skyrocketing.

Between January and September this year, Sudan exported 44 tons of gold abroad, bringing in revenue of $1.3 billion, according to Alhaj. That’s compared to just 23 tons in the whole of 2023 and revenue of $114 million.

In Sudan’s Red Sea state, Alliance for Mining Co. and Kush for Exploration and Production — two subsidiaries of the UAE-based Emiral Resources Ltd., a Russian-Emirati company founded by a former Russian diplomat and Gazprom PJSC executive — have restarted operations. A spokesman for Emiral said the company halted work in May 2023, soon after the war began, but resumed limited production this year and has exported 1.2 tons of gold to the UAE — under the terms of its original 2013 licenses — so far this year.

A gold bar at a laboratory in downtown Port Sudan. Business people weigh and test their gold for quality before selling it onwards or exporting it abroad.

The gold district in downtown Port Sudan. Both the army and the RSF have relied on the gold trade — which has revived since the conflict began — to fund their war effort.

Workers sorting pieces of gum arabic in a warehouse of an exporting company. Gum arabic, a natural emulsifier, is a key component in everything from pharmaceutical products to food.

Sudan is one of the world’s main producers of gum arabic. The government is selling it abroad as ways to raise funds for the war effort.

In May, Sudan and Qatar signed an agreement to open a gold refinery in Doha, which would reduce the reliance of Sudan on the UAE, where Alhaj said most of its gold is processed.

“The army is directly exporting the gold in order to bring in supplies of goods and weapons,” said Mohammed Ali Sawakni, chairman of the Red Sea Gold Traders Association. The army has also revived the export of gum arabic, a commodity used in a host of everyday commercial products, from toothpaste to sodas.

The increased revenue – and the weapons and drones it buys – has allowed the army to become more reliant on its air force to repel the RSF, which primarily fights using ground units and practices guerilla warfare using Arab tribes from Sudan, Chad and Niger.

Neither party appears ready for peace – neither do their foreign sponsors. And with conflict still raging in many parts of the country, the impact on the population is only getting worse.

Port Sudan’s few hospitals have been filled with refugees from the war and over 2 million are on the verge of death from famine, according to nutritional surveys conducted in October by Sudan’s Nutrition Cluster, a partnership including the UN, the Federal Ministry of Health, and NGOs.

Najet Ahmed, 47, arrived at Port Sudan’s Children’s Teaching Hospital with her five children after the RSF took over her home in Khartoum last year. She, like many Sudanese, blames foreign powers for her country’s plight.

A camp hosting internally displaced people at the Sal Al Bab Al Sharquia School for Boys in Port Sudan. Over 11 million people, nearly a quarter of Sudan’s population, are displaced.

People wait in line during the distribution of cash by the UN World Food Programme at the camp.

The nutrition ward of the Pediatric Center at Port Sudan’s Children’s Teaching Hospital. According to the UN, over 750,000 people are experiencing catastrophic levels of food insecurity in Sudan, with 25.6 million people in crisis levels of hunger. Between January and October of 2024, the center received 666 cases of severe or acute malnutrition cases.

“There is no willingness to stop the war. World leaders should come together and hold talks to bring peace,” she said. “But everyone has their own self interest. They just can’t agree.”