Katherine Ellena, Mario Mitre, and Patrick Quirk

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Election assistance and observation: A sound investment that improves electoral integrity

- Year of elections: Many consequential elections, inconsistent investment

- Looking ahead: Late 2024 and 2025

- Conclusion

Introduction

The United States and its allies are the most secure and prosperous when the world is free and open. Democracies value transparency, build stable economies, and make better trade partners. Democracies are more likely to cooperate on issues of counterterrorism, peace, and security. Democracies respect human rights and freedoms and share a common belief in the rule of law. For these and other reasons, the United States and like-minded allies use foreign assistance and diplomacy to strengthen democracy abroad. The two main tools are complementary: foreign assistance programs that strengthen the capacity of democratic institutions or actors within and outside government and US diplomatic engagement that champions local democracy advocates and holds despotic regimes accountable for their actions. A critical element of this support is the strengthening of elections—the processes that confer legitimate powers onto representative leaders.

This paper examines why and how the United States and its allies support free and fair elections as part of the broader democracy assistance agenda. It explains why US foreign aid for election assistance provides a valuable return on investment, discusses the hazards of underfunding US support for free and fair elections, and highlights priority elections in 2024 and 2025 where the United States and broader international community should focus their assistance efforts because these contests pose challenges, and opportunities, for US interests. The elections represent an opportunity to support citizens’ desire for a credible process, build confidence in democracy’s ability to deliver, and blunt the erosion of democratic values.

Elections as a core element of strong democracies

Free, fair, and transparent elections are a central element of strong, responsive democracies. Elections are a foundational mechanism for ensuring that sovereignty truly resides with citizens and that leaders are accountable to the people they serve. Many media outlets, academics, politicians, and pundits have declared that “democracy is on the ballot” around the world in 2024, which is the biggest election year in history as over seventy-five countries, representing half the world’s population, are holding national-level elections. However, we have learned over many decades that democracy is always on the ballot and that all elections can play a role in consolidating or derailing democracy.

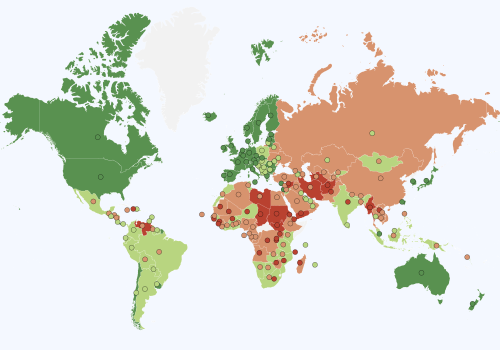

Despite democracy’s obvious advantages, which drove its expansion, particularly during the 1990s, a recent wave of autocratization has severely threatened the future of global democracy. Autocratic actors often target elections to undermine democratic principles and institutions, using ever-evolving and complex tactics to achieve their goals. According to the 2024 Freedom and Prosperity Indexes published by the Atlantic Council, democracy and measurements of clean and fair elections, in particular, have sharply declined since 2018, bringing the world to a twenty-year low. The challenges to electoral integrity are widespread and persistent, threatening the fundamental principles of democracy worldwide.

Within countries holding elections, authoritarian-leaning leaders are abusing power to skew the electoral playing field and compromise the integrity of electoral institutions. From South Africa to Mexico, politicians, non-state armed groups, criminals, and rivals have used violence to benefit their preferred candidate and attempt to sway election outcomes. Candidates are increasingly comfortable preemptively and without evidence casting doubt on election results—this has fueled citizen distrust in the integrity of electoral processes and led to threats or violence against election officials and nonpartisan citizen observers, also known as domestic observers. Predatory elites who benefit from the status quo use control of state financial resources and judicial institutions to strengthen their electoral chances and weaken or eliminate political opponents. Spoilers have used propaganda and corrupted the integrity of domestic information to suppress voter turnout. Political and economic instability have delayed elections altogether.

Threats to elections also come from actors external to the country convening the contests. Russia, China, and Iran routinely execute multipronged campaigns to exploit vulnerabilities in election infrastructures to advance their interests. This has resulted in, for instance, the attempted disruption of European parliamentary elections in Eastern Europe and the Balkans. The proliferation of artificial intelligence (AI)-generated information on digital platforms—which remain largely ungoverned—and their potential to pollute the electoral information environment pose a significant challenge to technology platforms, election administrators, political contestants, and voters. Platforms are stretched to keep pace with the tsunami of election-related information and remove inauthentic content, while election administrators scurry to develop and fund timely and effective response plans. At the same time, political contestants are often the target of misleading narratives, and voters must parse an increasingly cluttered media ecosystem for truthful insight into candidates’ policy positions.

In the lead-up to the United Kingdom’s general election on July 4, more than one hundred deepfake AI-generated video advertisements impersonating then British prime minister Rishi Sunak were promoted on Facebook, reaching four hundred thousand viewers originating from twenty-three different countries, underscoring the borderless nature of the modern risk environment. In countries with low literacy rates such as Pakistan, video content—whether genuine or fabricated—is particularly compelling for young voters whose primary source of information is social media.

Protracted assaults on elections, both internally and externally, threaten to corrode political and electoral institutions and contribute to waning public confidence that elections will deliver legitimate outcomes.

Foreign aid investments to advance free, fair, and credible elections are an essential strategic foreign policy priority and a cost-effective method for countering authoritarian “sharp power” around the world. Credible elections often open the door for more investment and economic assistance that result in increased economic development. Conversely, elections that are not credible can put access to aid and trade agreements at risk.

By contributing to credible elections, democracy assistance can mitigate violence and foster peaceful transitions of power, build the capacity of citizens to monitor and assess the quality of their elections, enable governments to effectively administer polls, and promote civic and voter awareness and participation. However, this type of assistance must be systems-based, not event-based. Framing the “year of elections” as a series of events masks the reality of what it takes to achieve and protect election integrity. The story of democracy in 2024 does not rest on the record number of ballots that will be cast over a record number of elections days, but on the weeks, months, and years that have come before, and those that will come after. Elections are not an event, but a process, and they require ongoing support, refinement, and protection.

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID), in its new “Democracy, Human Rights, and Governance (DRG) Policy,” is making an important pivot to emphasize the norms and values that must be cultivated to make institutions and processes truly democratic: “Political scientists have long suggested that the stability and effectiveness of democratic regimes depend in part on…the existence of a democratic ‘political culture’ that is unique to that context and enjoys widespread support.” As the policy notes, a focus on democratic culture should extend to election assistance, as “electoral processes are only meaningful when incumbents allow genuine political competition and the outcome reflects the will of the voters.” However, such a focus requires a more sustained, systems-based approach and to date US and international investment in such an approach remains mixed.

Election assistance and observation: A sound investment that improves electoral integrity

Assisting relevant actors to administer election processes that adhere to international norms and good practices, and encouraging transparency and oversight by citizen and international observers, can help mitigate existing and emerging threats and support free, fair, and competitive elections.

If designed and delivered well, election assistance can reduce barriers to voting, increase transparency in election operations, support informed dialogue around election technologies, address online and offline violence against women in politics and elections, and enhance civic participation. The international community also complements the work of national actors by conducting credible election observation consistent with international standards. International observation is particularly important to protect the political and civic space where such space is shrinking, contribute to stability in highly polarized environments, and provide an independent assessment of the process that complements that of citizen observers. International long-term election observation missions can deliver actionable recommendations and amplify those of citizen observers to improve elections over time.

In countries where institutions are captured or elections are a rubber-stamp exercise, support to democratic champions is still critical to nurture demands for democratic elections and provide the technical expertise to realize them when the opportunity presents itself. Democracy support in these closed or closing environments can create opportunities for coordination and action by connecting domestic actors with regional and global networks.

In spite of the global trend of democratic backsliding, there is evidence that the abovementioned type of assistance works. A 2020 study for the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) found a statistically significant positive contribution of international and Swedish aid to support democracy around the world. Findings suggest that this aid “correlates more strongly with democracy […] than developmental aid, because democracy aid targets the very institutions and agents of democratic change.” A key recommendation from the study is that Sida should consider increasing aid to “monitor and scrutinize electoral cycles, and also to strengthen the independence of electoral bodies that support free and fair elections.” The study also observes that pronounced declines in democracy are occurring in middle-income countries that are often excluded from democracy assistance because of their higher income status—reinforcing the fact that a traditional approach to aid allocation and electoral assistance is no longer viable in the new global threat landscape.

A 2021 study for the Expert Group for Aid Studies found that thoughtfully designed and implemented electoral assistance “can create enabling support structures for all actors genuinely committed to fair and credible electoral processes.” Emerging evidence suggests that this may be particularly true in countries deemed “bright spots” by USAID, as part of its “Democracy Delivers Initiative.” A 2023 study by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace’s Thomas Carothers and Benjamin Feldman examined thirty-two bright spots and the key political events that marked them, finding that fourteen of these bright spots made some significant democratic progress in the years since the bright spot juncture emerged, and it was instances of pivotal elections that more often produced lasting positive change.

In addition, a new working paper from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute offers an empirical overview of democratic “U-turns”—cases where countries on the road to autocratization reversed course toward more democratic paths. The analysis shows that 70 percent of autocratization cases turned around in the last thirty years, and 93 percent of U-turns ended with levels of democracy higher than, or similar to, those found before autocratization. While more study is needed, these findings seem to support citizens’ inherent thirst for democracy, and the need for electoral assistance to effectively support “U-turn” opportunities when they arise.

Investment in ongoing, long-term democracy and elections assistance is fundamental across the globe. In some cases, we may be able to help a democracy advance and consolidate; in others, we can support democratic champions to achieve a U-turn from episodes of backsliding. In recently consolidated democracies, assistance might help build resilience to emerging threats. Even in the harshest of environments, the United States and like-minded countries can support core aspects of democracy and preserve citizens’ demand for democratic space.

Year of elections: Many consequential elections, inconsistent investment

In 2024, while a record number of countries are holding elections, each will have its own characteristics. In Nigeria, off-cycle elections cover specific geographic areas; in the European Union (EU), they transcended national boundaries. Some elections will be focused on a specific class of seats, such as local authorities or the national parliament. In some countries, local-level elections will be more meaningful than national elections, both in terms of space for citizen engagement and their impact on people’s everyday lives.

Not all these elections will be credible. While many of this year’s processes will be seen as routine affairs, the continuation of a long tradition of credible elections, others will face significant challenges resulting from authoritarian tendencies among the ruling elites or the work of illiberal or illegal actors. Some elections will define whether a country will continue its democratic path or veer toward authoritarianism. Halfway through the year, we have already witnessed late changes to the legal framework in El Salvador to benefit the incumbent president, foreign efforts to influence the presidential election in Taiwan, and, in Mexico, the dual challenges of unprecedented political-electoral violence and efforts to undermine the integrity of the election authority. Countries once considered to have robust protections for electoral integrity, such as Indonesia and Mexico, have shown signs of backsliding. In extreme cases, such as Alexander Lukashenko’s Belarus and Vladimir Putin’s Russia, elections are smoke screens for the perpetuation of the ruling regime, without providing a real avenue for citizen participation and decision-making.

Even amid those challenges, citizens and other local actors have sought ways to preserve the democratic space, sometimes at great personal risk. In Senegal, stakeholders committed to democracy—including civic activists, election management bodies, and impartial judges—collectively pushed back against unconstitutional attempts at extending the presidential term and helped safeguard the rule of law and the will of the voters; similar hard-fought efforts in Guatemala ensured a peaceful transfer of power in January 2024. At their best, elections are exercises in locally led democratic development. Responsive political parties and candidates, professional election management bodies, an impartial judiciary, independent nonpartisan citizen election observers and journalists, and voters all play a meaningful role in ensuring elections are inclusive, transparent, accountable, and secure.

While recognizing this local ownership of election processes, the international community also has a significant role in promoting and protecting the integrity of elections, including local elections, around the world. The Global Network for Securing Electoral Integrity is working to strengthen electoral integrity norms and address emerging challenges. At a practical level, organizations like the ones we represent routinely provide local actors access to global good practices on election administration, political campaigning, citizen election observation, among others, that they can adopt to better contribute to democratic elections. A diversity of credible voices in international observation, such as organizations that endorse the Declaration of Principles for International Election Observation, signals multinational support for those democratic actors and processes under the highest threat, and broadens observers’ geographic coverage.

All these efforts require sufficient, timely, and coordinated financial support from development assistance agencies in the United States, Europe, and others in the community of democracies. To reinforce democratic gains made during elections—citizens that are more politically active, political leaders who are more responsive, and better-equipped democratic institutions, including election management bodies—and ensure lessons learned are applied in future processes, this support for local democratic actors also needs to be sustained between elections.

So far this year, investments by the international community have empowered citizen observers in Senegal to validate and build trust in the outcome of the presidential elections and bolstered transparency and public confidence in the administration of national elections in North Macedonia. When appropriate, USAID and other donors have strengthened local ownership of these processes by providing direct financial support to citizen observers and regional observation networks such as the Asian Network for Free Elections and the European Network of Election Monitoring Organizations.

For all the attention placed on 2024 as the “year of elections,” increased investment in long-term assistance to local institutional and civil society actors, backed by international election observation, is needed. As electoral integrity has come under complex and varied threats, US support for international election observation to hold political actors accountable has remained flat, and key countries facing sophisticated electoral threats have not received targeted support. This includes, most importantly, countries that are strategically important to the United States. In Mexico, for instance, the international community did not play a role in shoring up democratic institutions ahead of the biggest and most complex election in the country’s history on June 2, amid attacks on the independence of the National Electoral Institute, the Supreme Electoral Tribunal, and independent civil society. The May 29 elections in South Africa were a missed opportunity to hold the country’s political actors accountable through the timely deployment of observers to closely monitor and expose the ramifications of foreign influence on political contests, security and information environments, and, in the post-electoral period, the regional implications of a new governing coalition. In the lead-up to Taiwan’s January 13 elections, technical analysis of the information space, the role of civil society, and the resilience of the election commission could have elucidated valuable lessons in thwarting malign election interference in Asia and beyond. Furthermore, the timing of available funding in some countries did not allow for the full intended impact of electoral support or international election observation.

Looking ahead: Late 2024 and 2025

For the nearly one hundred countries that are scheduled to hold elections for the balance of 2024 and in 2025, the United States and the international community have an unprecedented opportunity to advance democracy around the world through foreign assistance that, in the short run, supports both electors and the elected, and in the long run, promotes in-depth local knowledge and capacity to administer and monitor credible periodic elections. These opportunities cannot be overstated. Applying sound principles to defend democracy from assaults on elections—such as building long-term institutional capacity, supporting resilient citizen monitoring institutions, and promoting political accountability through international observation—will ensure that newly established democracies resist backsliding and that investments are proactive and not reactive.

Building resilient, agile, and independent institutions

Parliamentary elections in Georgia in October will chart the country’s course toward a European future. Recent legislative changes initiated by the ruling party, including the controversial and consequential foreign influence law, are being challenged by citizens in Tbilisi and beyond, as well as international supporters of the country’s European aspirations. While it is unclear what impact this will have on elections, including whether international and local actors will observe the elections, and if current civic and voter education efforts are sufficient, sustained post-election support will be vital to support democratic actors, prevent further backsliding, and bring Georgia’s aspirations of EU integration back on track.

Tunisia, once a “bright spot” for democracy in the Middle East and North Africa, has experienced a precipitous decline in democratic governance. Tunisian President Kais Saied’s unilateral actions have undermined fundamental rights and dismantled democratic institutions, giving added importance to the October 6 presidential election in demonstrating what trajectory the country will take with its democratic journey. In 2021, Saied took control of the functions of the state and has since ruled by decree. Given the reduced space for credible international observation efforts, there is an urgent need to support actors in-country to preserve the little remaining democratic space that is left ahead of the October election. Against a backdrop of regional democratic backsliding, it is critical to support increased citizen oversight and mobilization to restore Tunisia as a democratic beacon to counter the behavior of authoritarian neighbors.

In Latin America, Ecuador’s February 2025 election will be a test of its electoral institutions, which have been holding consecutive elections almost every year since 2021, but are vulnerable to corruption and organized crime. Attempts to undermine the country’s information integrity and expand the use of illicit finance are also common. The country’s recent spike in violence resulting from an increased presence of organized crime will likely have a direct impact on the candidates’ ability to campaign free of threats and intimidation, the fair and transparent financing of campaigns, and the overall ability of voters to actively participate in the elections.

Gabon’s military leaders, who deposed former president Ali Bongo Ondimba in August 2023, currently oversee a transitional government with plans to hold a constitutional referendum in the fall of 2024 and presidential and legislative elections in August 2025. If successful, those elections will represent the first move toward genuine democratization in Gabon since the Bongo family came to power more than five decades ago. Thus, there is an urgent need to provide training and technical support for the national electoral commission, citizen-led groups involved in election observation, and robust national civic and voter education.

In Asia, the Philippines will hold national legislative and local elections in May 2025 amidst a growing political feud between President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. and the family of Vice President Sara Duterte. There is a risk of vote buying and potential violence in historically precarious areas, especially in southern Mindanao which will hold the first election in which the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region will elect members of its Bangsamoro Parliament.

Supporting timely international observation, political accountability, and peaceful processes

Mozambique will hold general elections in October 2024 amid endemic corruption (it ranks 145 out of 180 countries on levels of corruption, according to Transparency International) and an insurgency in the north that has led to large-scale displacement. The country also has a history of marred elections, including the manipulation of results in the 2018 municipal elections, the inclusion of hundreds of thousands of ghost voters and the blocking of citizen observation in the 2019 national election, and ballot stuffing and voter intimidation in the 2023 local elections. The presence of international observers in this year’s elections would help deter manipulation attempts, protect space for citizen observers, and allow for specific recommendations to strengthen the integrity and credibility of future Mozambican elections.

Moldova’s upcoming trifecta of elections—a referendum on EU accession and presidential elections in October this year followed by parliamentary elections to be held no later than July 2025—will have a direct impact on the country’s reform agenda and European aspirations. In October, citizens will decide whether to reelect President Maia Sandu, one of the most outspoken advocates for reform in the region and approve enshrining Moldova’s intention to join the EU in its constitution. Voters will have an opportunity to cement these choices in next year’s parliamentary elections. Moldova’s recent local elections indicate increased attempts by Russia to interfere, which should be closely monitored. Attempts to cast doubt on the legitimacy of the 2024 elections have already begun. To combat Russian hybrid warfare attacks and support Moldova’s EU path, more efforts should be made to support international election observation, electoral cybersecurity infrastructure, and education to minimize the risk of attacks on electoral legitimacy.

With closing democratic space and a steady rise in polarization and political violence since 2020, there are serious concerns about the security of Ghana’s general elections in December. The country might be vulnerable to violent extremism spreading from the Sahel that could further undermine its stability. Should Ghana’s standing as a model democracy in West Africa further erode, it would have a negative spillover effect in neighboring states such as Benin, Cote d’Ivoire, and Togo, all slated to conduct national elections in 2025 or 2026. Given Ghana’s influence in the Economic Community of West African States and the country’s significance as a US security partner in an already fragile region, robust investment in the independence, credibility, and resilience of Ghana’s democratic institutions is critical. This should be coupled with US investment in international electoral observation to help mitigate political violence and reduce the likelihood of spillover in the subregion.

Previous elections in Ethiopia were marred by conflict that led to the exclusion of several regions. Elections in the fall of 2025 will provide another test for Ethiopia’s electoral institutions and processes and whether the dominant political party, the Prosperity Party, can resolve subnational conflicts, particularly in Tigray, Amhara, and Oromia regions, and fully implement some of the reforms promised in 2018, including transitional justice and national dialogue processes. Previous international observer recommendations in Ethiopia called for national cohesion and strengthening independent institutions. The 2025 election will be both an opportunity to assess Ethiopia’s progress toward that end and a chance to test the independence of Ethiopia’s institutions.

Malawi is a bright spot amidst continental democratic backsliding, though there are signs that citizens are growing frustrated that new governments consistently fail to deliver on their promises to voters. Following the 2020 rerun presidential election, which brought the Malawi Congress Party to power through a campaign coalition, political fissures were already deep ahead of the September 2025 elections before the death of Vice President Saulos Chilima in a plane crash on June 10. With increased political fragmentation and the likelihood of elections being resolved through a second round for the first time, it will be critical to support Malawi‘s electoral authorities to deliver technically sound elections and ensure international and citizen observers can provide an objective assessment of the credibility of the process.

In Central Africa, Cameroon’s ninety-one-year-old president, Paul Biya, is the world’s oldest president. The country will hold presidential and legislative elections in the fall of 2025, yet less than half of the population is registered to vote, presenting a tremendous need to support independent institutions and educate citizens on their voting rights. Given the lack of transparency in past elections, it will also be important to deploy election observers to help increase voter confidence and mitigate the potential for violence.

Bolivia is scheduled to hold presidential and legislative elections in October 2025 which will have serious implications for the country’s frail democracy. Given Bolivia’s history of political polarization and violence, it’s likely that insecurity in the lead-up to elections will intensify. In June, Bolivian President Luis Arce and the Movement Toward Socialism (Movimiento al Socialismo) narrowly avoided an apparent coup attempt amidst public criticism for corrupting the judicial system and jailing political opponents. The election offers an opportunity for the international community to signal its support for the development of robust democratic parties that represent Bolivia’s rich cultural and ethnic diversity.

In Honduras, more than five million citizens will elect the president, national legislature, and municipal councils in November 2025. While Honduras has made marginal democratic gains, it consistently ranks low (0.53) on the V-Dem Institute’s Electoral Democracy Index for political polarization, abundance of false information, risk of electoral conflict, and susceptibilities to foreign authoritarian influence, raising concerns about its democratic trajectory and increasing the need to finally have the new electoral procedural law in place, together with robust citizen and international observation, to mitigate the potential for election violence.

Conclusion

This year’s unprecedented number of elections at a time when democracy and measurements of clean and fair elections, in particular, have experienced a sharp decline since 2018 presents an opportunity for the United States and its democratic allies to lead the charge to strengthen universal norms in support of electoral integrity—which are persistently under threat from new and evolving challenges—and to counter the proliferation of malign influence.

Challenges such as the rise of illiberal election observation missions that lend credibility to fundamentally flawed elections, the introduction of repressive laws to restrict or silence civic and political participation, and the expansion of illiberal state actors’ assault on democratic values writ large demand a more proactive and comprehensive approach and present an urgent need for the United States to execute thoughtful, evidence-driven electoral assistance plans. Investments in building strong electoral institutions that are responsive to citizens and resilient to external influence will yield dividends in countering malign actors that seek to undermine public trust and confidence in the process.

While elections are not an event, an endgame, or an exit strategy, the United States should lead the international community in supporting electoral processes and institutions in ways that provide an effective return on investment and that recognize elections for what they represent to global democracy. Where the conditions for international observation are present, the United States can support observation missions to signal international backing for the aspirations of citizens to choose their leadership and gain recognition in the global community of democracies.

Likewise, where there are opportunities to empower citizen observers to independently assess the quality of their elections and to help governments advance electoral reform agendas and deliver meaningful progress, the United States and others can play an important role in recognizing and amplifying these successes, reinforcing the message of freedom and prosperity that democratic systems beget.

About the authors

Katherine Ellena is vice president of programs at the International Foundation for Electoral Systems.

Mario Mitre is senior adviser for elections and political processes at the National Democratic Institute.

Patrick Quirk is nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Freedom and Prosperity Center.

Explore the data

Related content

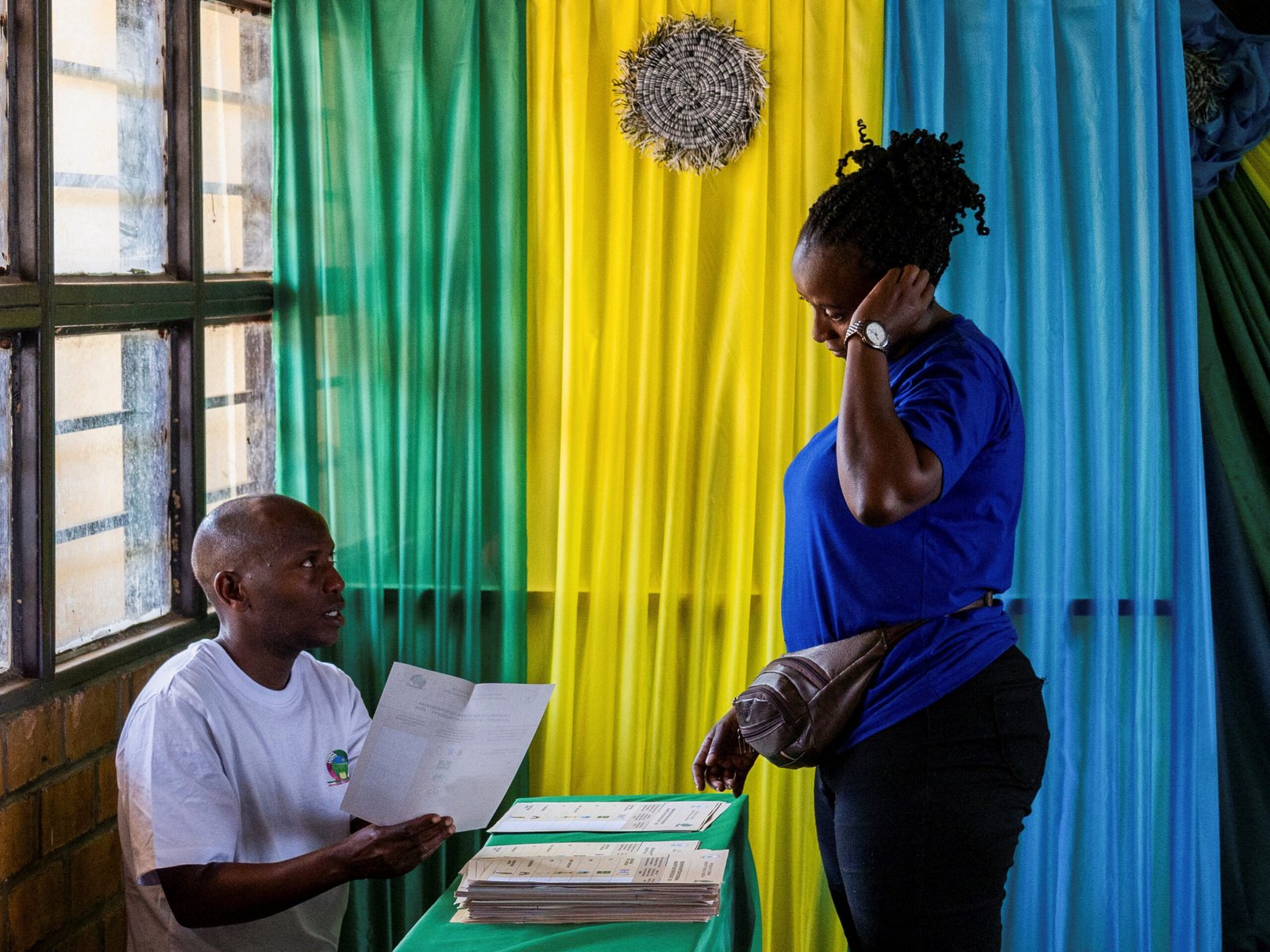

Image: A voter is processed by an official from the Rwanda National Electoral Commission (NEC) before casting her ballot during the presidential election at the GS Kagugu polling centre, in Kinyinya, Gasabo district of Kigali, Rwanda July 15, 2024. REUTERS/Jean Bizimana