By John Richardson

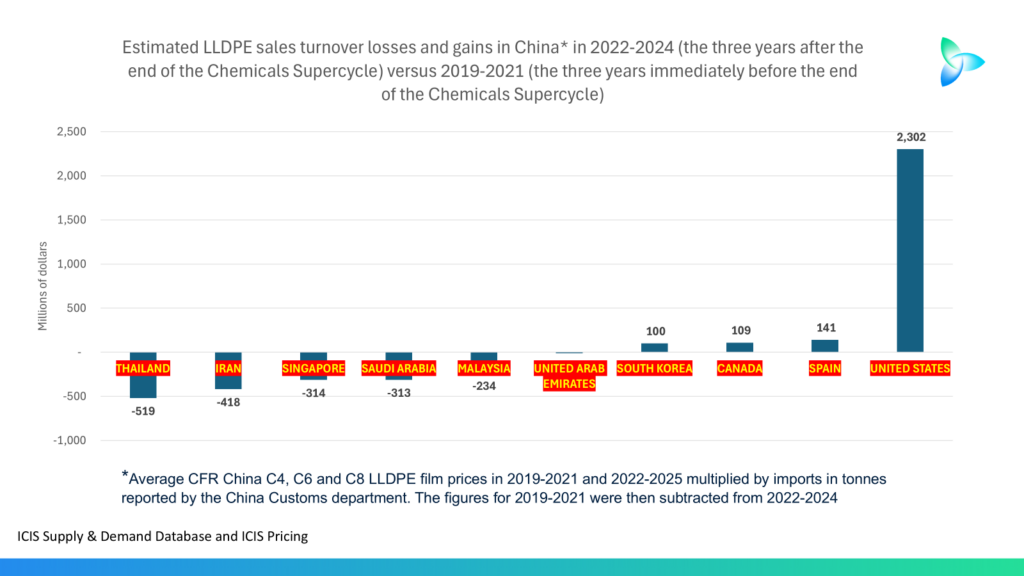

THE ABOVE SLIDE, as with my slide earlier this week on HDPE, shows the extent to which China’s LLDPE market swung in favour of the US in 2021-2024. This was during the three years after the end of the Chemicals Supercycle compared with the three years immediately before the end of the Supercycle, which was from 2019 until 2021.

The post-Supercycle years have been characterised by Chinese chemicals and polymers demand growth probably in the low single digits, lower I believe than conventional estimates suggest, because the country’s GDP growth was likely much less than the official numbers.

Across many chemicals and polymers, China’s self-sufficiency also significantly increased during the first three years after the end of the Supercycle versus the previous three years, reducing the need for imports. China’s LLDPE capacity as percentages of local demand rose from a 2019-2021 average of 64% to 74% in 2022-2024. In contrast, however, HDPE capacity over demand rose more sharply from 56% to 79%.

The US sales gains are stunning. US LLDPE sales turnover in China increased by $2.3bn while most of China’s other top ten trading partners saw declines in their turnovers. Thailand saw the biggest decline at $519m followed by Iran at $418m and Singapore at $314m.

US turnover surged as the imports reported by China from the States jumped by 190% to 3.1m tonnes. Meanwhile, as the table below shows, several of the other top ten trading partners saw their imports slip. But there were other winners: South Korea, Canada and Spain.

Total imports during the two three-year periods fell from 17.9m tonnes to 17.5m tonnes, a decline of just 3% which was likely down to demand holding up well despite the economic downturn. This seems to reflect LLDPE’s dominant use in packaging applications which have been less vulnerable to the slowdown compared with durable goods end-uses.

In contract, HDPE imports fell by 29% to 16.8m tonnes, reflecting a higher level of self-sufficiency compared with LLDPE. Another factor could have been a slowdown in the demand growth for HDPE pipes because of the collapse of the property bubble.

The US tariff advantage versus other explanations

My ICIS colleague, Joe Chang detailed, in a June 2024 article, how the US/China PE trading relationship evolved between 2019 and 2020:

First, there were tariff rollbacks by the US as well as China by December 2019 on the striking of a trade deal. Many tariffs remained in place, though at lower rates.

Then critically in February 2020, China offered importers waivers on certain tariffs imposed on US PE and other plastics and chemicals imports.

For various types of US high-density PE (HDPE) and linear low-density PE (LLDPE), on which a 34% tariff rate applied, Chinese importers could apply for a waiver and instead pay the pre-trade war duty of 6.5%.

What else might have been behind the huge gains that the US made in the China market? Perhaps they exported more C6 and C8 grades to China versus competitors which were in higher demand than C4 grades because China’s economy is maturing. Its conversion industry is becoming ever-more sophisticated.

I don’t have the data to support this theory unfortunately. But as we look forward to what might happen next, here is a piece of advice to all LLDPE exporters to China: Assess levels of Chinese demand growth across the different grades and ensure your production of different grades matches the patterns.

But this of course depends on the extent to which producers can make the right quantities of C6 and C8 versus C4 grades. Are you sufficiently diversified into the grades with the strongest performance? What can you do to change your production mix if you fall short?

And most obviously, the US and its competitors need to prepare for anything from a new and full-blown US/China trade war versus a better trading relationship and anything in between these two extremes. This is due to the nature of the new White House administration. A return to Chinese tariffs of 34% on US LLDPE may swing the market back in favour of Thailand, Saudi Arabia and South Korea etc.

A big potential surge in Chinese LLDPE self-sufficiency

We must also consider forecasts for Chinese self-sufficiency levels to predict what will happen next in its LLDPE market. Here are some comparisons with HDPE, based on the ICIS data:

- China’s capacity as a percentage of HDPE demand is forecast to rise to 84% this year from 80% in 2024. It is expected to reach 94% by 2030.

- LLDPE is forecast to rise to 88% this year from just 74% in 2024. And by 2027, it is expected to pass 100% for the first time, reaching 112% in that year before falling to 109% by 2030.

Capacity is of course not the same as production, with production driven by local plant economics.

We must also consider all the uncertainties over the pace of Chinese chemicals capacity growth in general given a potential decline in the availability of local feedstocks due the cap on refinery capacity. The cap on further refinery capacity additions beyond 2028 is the result of the rapid growth in electric vehicle-sales in China.

But China might decide to import more feedstocks and maintain an aggressive building programme. Or it may choose to maintain or grow LLDPE imports as the number of local plants that come on-stream is fewer than we expect.

A further uncertainty is the extent to which chemicals capacity will expand in China as the country aims to hit its carbon-reduction targets.

“A minimum 28% reduction in total GHG [greenhouse gas] emissions from 2023 levels by 2035 is crucial for China to stay on track for its 2060 domestic net-zero target, assuming a linear decline in emissions from the peak to 2060,” wrote Carbon Brief in this November 2024 article. Carbon Brief added that this reduction excluded the effects of land use, land-use change and forestry.

Watch for the details of China’s next five-year-plan, which will run from 2026 until 2030, and how this will apply to chemicals. How will China balance its long-running chemicals self-sufficiency drive versus the carbon-reduction targets under the new plan?

What about the closure of older chemicals plants? Have we reached the point where closures are going to accelerate as some of China’s steam crackers are now more than 20 years old? How many have been revamped to be in effect new crackers versus the smaller units where such investments haven’t been seen as cost effective?

There is an unconfirmed report that China wants to close some of its coal-based chemicals capacity for environmental reasons. How would this effect China’s LLDPE supply and demand balances?

Here is a further thought suggested to me by one contact: As the world in general becomes perhaps more protectionist, will we see a big surge in antidumping and safeguard claims and investigations? This of course doesn’t just apply to LLDPE and could affect a wide range of countries.

How might this reshape chemicals and polymers exports from and imports to China? Watch this space as I explore more.

Want to know more? Contact me and I will put you in touch with our ICIS experts as we navigate this complexity together.