Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

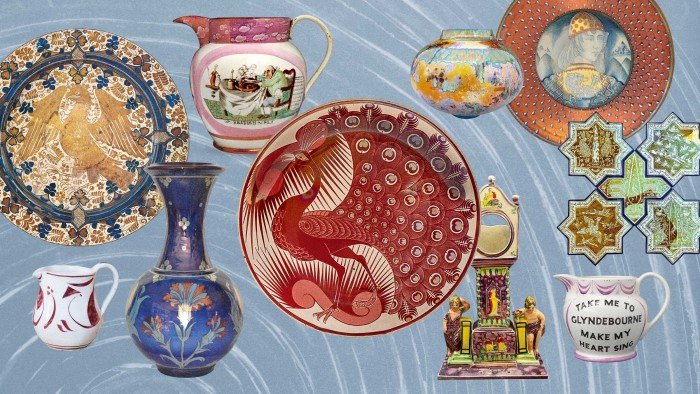

Even in midwinter at Great Dixter in Sussex, the Peacock Garden is aglow with cotoneaster berries, witch hazel starbursts and the bronze skeleton seedheads of giant fennel. So much so, one could be forgiven for bypassing the interior of the 15th-century house. But to do so means to miss the lustred vessels of Alan Caiger-Smith, master British potter of the 20th century.

Christopher Lloyd, the late owner of Great Dixter, amassed about 30 pieces of Caiger-Smith’s, from a modest set of red-and-white jugs, still in use in the kitchen, to a sweeping dish swirled with iridescent brushstrokes of red lustre.

Caiger-Smith was both an innovator and a renowned scholar of his craft. His co-translation of western Europe’s first detailed treatise on ceramics, Cipriano Piccolpasso’s Tre Libri Dell’Arte Del Vasaio (1557), reveals the risks and expense shouldered by the lustre masters of the Italian Renaissance, whose work involved overpainting ceramic with copper or silver compounds, then undertaking a daring, third “reduction firing” in a wood-fired kiln (Piccolpasso suggests that as few as six pieces in 100 came out of the lustre kiln successfully).

Earlier still, it was the Iraqi potters of the ninth century who invented lustreware, in a technique adapted from glass-making. The technology spread west, into the palaces of southern Spain and Italy, prevailing as a cultural thread between Muslim, Jewish and Christian potters. Medieval makers and buyers were bewitched by lustre’s alchemical mysteries; in 1301, a potter in the Persian city of Kashan praised it for “shining like the light of the sun”. And its complexity has rarely failed to lure elite collectors, many of whom today are drawn to contemporary innovators.

A lustre plate by Patrizio Chiucchiu

Contemporary lustre tiles by Abbas Akbari from Kashan in Iran

A Sunderland jug with a cartoon by satirist James Gillray

A vase by Jonathan Chiswell Jones and Kerry Bosworth, sold for £250

In the Renaissance, “there was already a considerable premium on lustre”, explains Timothy Wilson, former keeper of western art at the Ashmolean museum, Oxford. At the Christie’s Rothschild Masterpieces sale in 2023 – a collection formed by the Rothschild family – a lustre maiolica plate from 1533 achieved $163,800, and three other items exceeded $300,000, with one reaching more than $1mn. The “pièces de résistance”, says Wilson, “are the polychrome lustres, made in the workshop of Maestro Giorgio in Gubbio from around 1495”. One can only imagine “the wonder of seeing, for the first time, the metallic sheen of lustrewares during a Renaissance banquet lit with torches”, adds Elisa P Sani, a curator and art historian.

Today’s collectors are equally enraptured by Islamic antiques. In the past 10 years, as concerns for provenance have sharpened, “the market has become a lot more refined”, says Oliver White, head of the Islamic and Indian art department at Bonhams. Some of the most desirable antiques include Kashan zoomorphic jugs, intricate Hispano-Moresque albarelli and pieces inscribed with figures or calligraphy. One gem, currently on sale at Barakat Gallery, is an 11th- to 13th-century Persian globular jug incised with a series of verses in gold lustre (POA). But “it is doable”, says White, “to find a small 12th-century Kashan dish for a few hundred pounds, in imperfect condition”.

A c1890 lustre plate by William De Morgan, from his early experimentation into making lustreware

A c1456-1461 Hispano-Moresque lustred armorial charger, which sold for more than $1mn at Christie’s

The British 19th-century maker William De Morgan was the reviver of lustre in the arts & crafts style, and a mid-priced De Morgan piece commands around £5,000-£10,000 at auction (1stDibs is selling an angular-handled vase decorated with dragons for £8,900). For figurative designs using less purist methods, look to the fabled Wedgwood Fairyland lustre, designed by Daisy Makeig-Jones between 1915 and 1931. Vases, pedestal bowls and malfrey pots, bristling with tableaux of goblins, scrolling dragons and ghostly woods, continue to reach between £500 and £20,000 at auction.

WHERE TO BUY

1stdibs 1stdibs.com

Anderson & Garland andersonandgarland.com

Barakat barakatgallery.eu

Boldon Auction Galleries boldonauctions.co.uk

Oxford Ceramics Gallery oxfordceramics.com

Tennants tennants.co.uk

WHERE TO SEE

Castello Sforzesco milanocastello.it

The De Morgan Foundation demorgan.org.uk

Great Dixter greatdixter.co.uk

V&A Museum vam.ac.uk

WHAT TO READ

Alan Caiger-Smith and the Legacy of the Aldermaston Pottery by Jane White, accartbooks.com

Staffordshire and north-eastern Sunderland lustreware (with a pink glaze) remains desirable, too. Plaques and tableware made for the lower middle classes were furnished with maritime motifs, political and religious messaging and love poetry. “The appeal of Sunderland, to me, is its painterly decoration,” says Stephen Smith, a collector of more than 20 years. “Many pieces are one-offs – so you have a direct connection with the painter.” The finest objects hail from 1820-1845, and the rarest (puzzle jugs, commemoratives or plaques depicting moments of social history) can reach four figures. Alternatively, jolly Sunderland teaware can start from £20 to £200 (on eBay or with auction houses Anderson & Garland, Boldon Auction Galleries and Tennants).

A modern take comes from Gloria Baker of Sussex Lustreware, which is stocked at Tom Paine Gallery, Lewes – her pink lustreware mugs, jugs and plaques are stamped with contemporary ditties. “Take Me to Glyndebourne, Make My Heart Sing”, says one jug. “They tell us stories about who we are,” says Baker. “They connect us to those who went before us and those we give them to – whether as rallying cries or tokens of affection.”

A c1820 Sunderland watch stand in the form of a longcase clock, sold by antiquepottery.co.uk

A c1985 Sutton Taylor footed bowl, sold for £1,550

One of a pair of lustreware cream jugs made for Christopher Lloyd of Great Dixter by Alan Caiger-Smith in 2003

Sussex Lustreware Glyndebourne jug, £75

Other contemporary makers remain in thrall to lustreware. If one misses a rare Caiger-Smith vessel, (Oxford Ceramics Gallery recently sold a particularly fine brick-red bowl from 1977), look to Sutton Taylor, Andrew Hazelden or Jonathan Chiswell Jones, all selling with regional galleries. “The quest for authenticity characterises a lot of today’s lustre potters,” says Fuchsia Hart, the Sarikhani Curator for the Iranian Collection at the V&A. “Many are invested in the long history they are inheriting. So if you collect their pieces, you are actually participating in an appreciation for all the amazing places where lustre has flourished.”