By John Richardson

YOU SHOULD continue to prepare for anything between an improved trading relationship between the US and China, a full-blown trade war or anything in between these two extremes.

You can argue that this has ever been such or that the new White House administration has led to much greater uncertainty. Whatever. This is a side issue. What we do know for certain is that no “one-size-fits-all” scenario will help you forecast what’s going to happen next in chemicals and polymers markets during the rest of 2025 because of US trade policy towards China and an ever-widening range of other influences.

What’s interesting about the polyethylene (PE) world is that the US/China trading relationship strengthened from 2020 onwards following the disruption of the tit-for-tat imposition of tariffs by the two countries in 2018.

My ICIS colleague, Joe Chang detailed, in a June 2024 article, how this PE trading relationship evolved between 2019 and 2020:

First, there were tariff rollbacks by the US as well as China by December 2019 on the striking of a trade deal. Many tariffs remained in place, though at lower rates.

Then critically in February 2020, China offered importers waivers on certain tariffs imposed on US PE and other plastics and chemicals imports.

For various types of US high-density PE (HDPE) and linear low-density PE (LLDPE), on which a 34% tariff rate applied, Chinese importers could apply for a waiver and instead pay the pre-trade war duty of 6.5%.

This helps explain the big surge in US exports of HDPE and LLDPE to China since 2020, In this post, I will just look at the data on HDPE. LLDPE will be the subject of a later post.

But it is unlikely to be just the fall in Chinese tariffs on US HDPE that explains the dramatic change in trade flows between these two countries. Bear with me as I explain why this is surely a much more complex story. It will take a while.

Let’s start unravelling this particular ball of tangled string by considering the chart below.

The chart shows integrated HDPE variable cost margins for four countries and regions: The US Gulf, the Middle East Gulf, Southeast Asia (SEA) and Northeast Asia. (NEA).

The pandemic upended global chemicals and polymers markets in many ways. For example, as illustrated here, NEA and SEA HDPE margins were briefly as good as US and Middle East margins during 2020, despite the latter two’s ethane feedstock-cost advantages.

I believe that this reflected reduced availability of feedstocks from refineries because of the big dip in demand for transportation fuels. Chemicals and polymers supply thus tightened as demand improved because of big government stimulus programmes. Most of the stronger demand for finished goods, resulting from the stimulus, was met by China, thus boosting its chemicals demand.

Just look at what has happened since the Evergrande Moment in late 2021. NEA and SEA margins have collapsed and have often been in negative territory for most of the time since then, reflecting far-too-much capacity chasing too little demand.

But feedstock-cost advantages have left both the Middle East and the US in very strong positions, as you can see from the blue line for the Middle East Gulf and the green line for the US Gulf.

But even with the Middle East feedstock advantages, China’s reported imports from Saudi Arabia fell very sharply in the three years from 2022 until 2024 compared with 2019- 2021. This was as imports from the US surged. Note that Saudi Arabia’s ethane costs have risen over recent years and are reported to have risen again in January this year, although I haven’t been able to confirm the extent of any increase.

China’s HDPE mports from Saudi Arabia fell by 40% to 3.2m from 5.4m tonnes as imports from the US soared by 120% to 1.8m tonnes from 0.8m tonnes.

We can make more immediate sense of the declines in imports from Iran because of the sanctions limiting production and from South Korea because feedstock-cost disadvantages, making it very difficult for South Korea to compete in a lower-priced market.

See the chart below showing the increases and declines in HDPE imports reported by China among China’s top ten trading partners in the context of lower total imports and lower pricing in 2022-2024 versus 2019-2021.

Maybe production issues in Saudi Arabia played a role here. Or was it to do with the mix of grades supplied by both countries? Did the US supply more of the increasingly sophisticated grades China is importing in bigger volumes as it becomes much more self-sufficient in the basic commodity grades? China is becoming more of a higher-value markets as its economy matures (this a theme I shall explore in detail in a later post).

Back to the issue of rising ethane feedstock costs in Saudi Arabia. How important a role was played by more expensive Saudi ethane versus cheaper US ethane?

US HDPE’s big sales turnover gains since the end of the Chemicals Supercycle

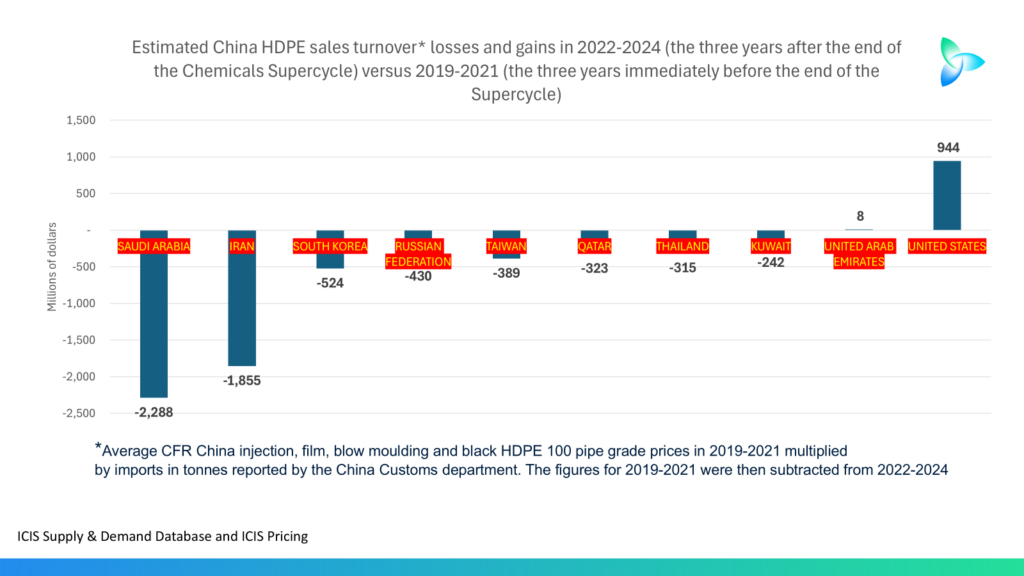

We can take the ICIS HDPE data further and produce estimates of HDPE sales turnover in China for the country’s top ten trading partners.

Just to note before I present the slide: I have compared 2022-2024 with 2019-2021 as these are the three years after the end of the Chemicals Supercycle (1992-2021) versus the three years immediately before the end of the Supercycle. The ICIS margins data in the first chart, our operating-rate data and the numbers on capacity exceeding demand show the value of comparing these two periods. Early 2022 is when the downturn clearly began.

Saudi Arabia’s sales turnover in China was down by an estimated $2.3bn in 2022-2024 versus 2019-2021. Iran was 1.8bn lower and South Korea 0.52bn lower. In contrast, the US was nearly a billion dollars in the black.

The “known unknowns and the “known knowns”

Here’s the full and famous quote from former US Secretary of Defense, Donald Rumsfeld:

Reports that say that something hasn’t happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don’t know we don’t know. And if one looks throughout the history of our country and other free countries, it is the latter category that tends to be the difficult ones.

In the context of this post in what I hope will help with your planning for the rest of 2025:

- A “known, unknown” is that nobody has a clue about the outcome of US trade policies towards China (you might argue it has ever been so or that we now live in a new era of much-greater volatility. But that’s a side issue). So, prepare for anything from improved China/US trading relationships to a full-blown trade war and anything in between these two extremes.

- A “known, known” is that the US has over the last three years emerged as a winner in HDPE exports to China during what is at least a medium- term (this a second “known, known”, I believe) Chinese economic slowdown and the country’s rising HDPE self-sufficiency. This has been at the expense of Saudi Arabia, Iran and South Korea etc. as we can see from today’s first chart.

- So, we need a range of scenarios on our first “known, unknown” about how a range of policy outcomes could reshape global HDPE trade flows and HDPE sales turnover in China,

- But another “known, unknown” is the extent to which lower Chinese import tariffs on US HDPE from February 2020 onwards has led to the US being a winner versus its feedstock advantages. Since the Evergrande Turning Point, its feedstock advantages over the Middle East as a whole have been slight, but huge over Northeast Asia and Southeast Asia. Further, we don’t know the degree to which the mix of grades exported to China has also played a role. China is increasingly able to meet its commodity-grade needs but still requires substantial imports of higher-value grades as its economy matures.

- This leads us to our final “known, known”: That scenario modelling has become much more complex. Different assumptions on all the above variants, and probably more that I haven’t even thought of, need to be factored in as we assess future HDPE trade flows to China and earnings in China by the big exporters. This is where ICIS can help you including our evolving Ask ICIS artificial intelligence solution.

Why make life hard for yourself by not making maximum use of AI? Don’t be a Luddite because the answers are not perfect now. AI will get better the more we work with it.