Editor’s Note: Sina Azodi is an assistant professor of Middle East politics at George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs, specializing on Iran’s national security policies and a frequent contributor to Stimson. Zandi is a geopolitical analyst, PhD student and research assistant in the department of political science at the University of Kansas, specializing in Middle Eastern politics and Iran’s gray zone strategies.

By Barbara Slavin, Distinguished Fellow, Middle East Perspectives Project

In assessing the rapidly evolving dynamics of the Middle East—particularly those involving Iran—one often overlooked yet critical factor is the enduring force of historical memory and national humiliation.

For a country like Iran, whose modern history is marked by repeated episodes of military occupation, foreign-backed regime change, territorial threats from neighbors, and the erosion of political sovereignty, any event that reopens these historical wounds can carry serious implications for both regional and global security.

These memories form a volatile reservoir of collective resentment that, if triggered, could ignite far-reaching instability. In such a scenario, the consequences may prove far more catastrophic than what has already unfolded in Gaza or Syria over the past few years.

Even as a tentative ceasefire went into effect between Israel and Iran and the U.S. and Iran after 12 days of conflict, it is essential for policymakers to recognize that for Iran, national security is not defined solely in military or strategic terms. Rather, it is deeply bound to the collective memory of humiliation shaped by a long history of foreign intervention and perceived betrayal. One could argue that the very emergence of the Islamic Republic—and its confrontational posture toward the West—has been shaped by this enduring historical narrative. Failing to recognize this emotional and psychological dimension risks misreading Iran’s responses and underestimating the broader regional consequences of escalation.

The Roots of the Wound

The sense of national humiliation in modern Iran over at least the past century is not merely an emotional or cultural phenomenon; according to many scholars, it was also one of the principal roots of the 1979 revolution. During both World Wars, Iran, despite its announced neutrality, was invaded and occupied by foreign forces. In the aftermath of Iran’s occupation by Soviet and British forces during World War II, Reza Shah Pahlavi, the father of the last Shah, was forced to abdicate because of alleged pro-German sympathies. Despite the commitment of Allied forces to respect Iran’s territorial integrity and independence and withdraw all troops from Iran at the end of the conflict, Soviet forces not only refused to leave but actively undermined Iran’s efforts to restore order in Azerbaijan province. This period left a vivid memory of foreign-backed threats of annexation and secession, fostering deep resentment toward Russia in the collective Iranian consciousness that continues to resonate today.

Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who was installed on the throne after his father’s forced abdication, described this experience, stating, “Twice our country was occupied in the first and second World Wars… And what things did we endure during that occupation… This is a two that will never become three. Let me explain, that means with our acceptance it will never become three. If it happens it will be over our corpses.”

But foreign interference in Iran did not end and the young Shah was initially a beneficiary. The government of Mohammad Mossadegh, the nationalist prime minister who sought political and economic independence for Iran, was overthrown in 1953 in a joint CIA- and MI6-backed coup that put the Shah – who had fled the country – back in power. Beyond the restoration of the monarch, public confidence in the possibility of independent, gradual reforms arising from domestic political efforts was gravely undermined.

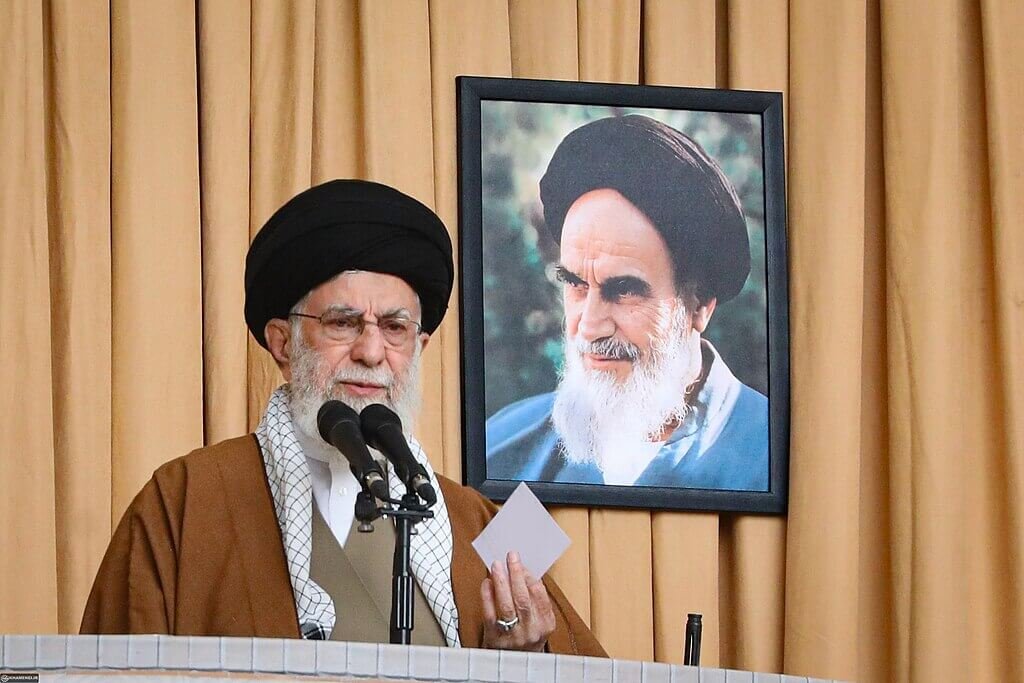

Following the coup, Iran’s military, cultural, and intelligence reliance on the U.S. significantly increased. To many Iranians, this growing dependency represented a continuation of national humiliation. One of the most controversial symbols of this subordination was a Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) in 1963, which granted U.S. military and civilian advisors legal immunity from Iranian jurisdiction. This affront to Iranian sovereignty provoked widespread public outrage. It was in this charged atmosphere that Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, then emerging as a central figure in the opposition to the Shah, directed his critique against the concept of “capitulation.” By framing the issue as a betrayal of national dignity, Khomeini tapped into deep-seated resentments. His stance became a key factor in the growing momentum of the revolutionary movement that would eventually topple the monarchy.

The product of this sense of national humiliation and fear of foreign domination produced the slogan “Neither East nor West” as the foundational principle of the Islamic Republic’s foreign policy. This motto emerged directly from a psychological backdrop of shame, anxiety about external powers, and concern over foreign dependence. It signaled a deliberate break from past alignments and an assertion of autonomous identity in the international arena.

Yet Iran’s rejection of foreign alliances – and seizure of U.S. hostages during the government’s post-revolutionary consolidation – left Iran isolated after Iraq invaded in 1980. Throughout the eight-year conflict, Western powers, most Arab states, and even the Soviet Union overwhelmingly backed Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein. Iraq deployed state-of-the-art Western-supplied weaponry, including chemical arms—particularly from France and Germany—against Iranian forces and civilians, all while benefiting from U.S. intelligence support. Despite egregious violations of human rights, the international community largely turned a blind eye. For Iranians, this period became deeply etched in the national consciousness as a moment of solitary resistance in defense of sovereignty and dignity. It further cemented a prevailing narrative that Iran must always be prepared to defend itself against foreign betrayal and aggression.

At a moment when any fundamental shift in Iran’s political structure could be accelerated from within or instigated by external powers, all stakeholders must pay careful attention to Iran’s history, culture, and socio-political fabric. Beyond targeting Iran’s nuclear and missile programs, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu at one point described Israel’s war on Iran as one of “liberation” and a government spokesperson acknowledged that a regime change could be a byproduct of the campaign. The bombing of Tharallah Base—responsible for protecting top officials and key institutions of the Islamic Republic—could be seen as a signal of Israeli intentions to weaken Iran’s central government and to force a collapse of the regime. Iranian analyst Diako Hosseini raised the alarm on social media by stating that several reports indicated that light arms “suitable for urban warfare” have been smuggled into the country.. which apparently mean [Israel’s plans for] Iran’s disintegration through civil war.”

President Donald Trump’s social media threat on June 22 about possible regime change in Iran added to the speculation that collapse of the Iranian government is also the U.S. goal. Explaining Trump’s position, White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt stated, “If the Iranian regime refuses to come to a peaceful, diplomatic solution, which the president is still interested and engaging in by the way, why shouldn’t the Iranian people take away the power of this incredibly violent regime that has been suppressing them for decades?”

While Trump’s remarks might be interpreted as a pressure tactic, it was unprecedented from a U.S. leader in recent decades.

However, external intervention risks producing an outcome far graver than the status quo. Such a scenario could give rise to conditions comparable to—or even surpassing—the Syrian civil war, fueling hatred and calls for revenge against aggressors and interveners. That, in turn, would plunge the region into a new phase of profound instability.

Modern Iranian history is marked by episodes in which national humiliation has driven society toward radical responses. The takeover of the U.S. Embassy in November 1979 was, in part, a reaction to the lingering trauma of the 1953 coup as well as an effort by the new clerical regime to purge remaining pro-Western political factions and to outflank the left. Today, there is a genuine risk that any push for a radical political change in Iran could backfire and alienate the population. Now more than ever, it is essential to approach Iran with a nuanced understanding that respects its historical identity, acknowledges past grievances, and charts a path forward grounded in empathy and cultural insight. Such a process should and could naturally emerge from within existing political structures and proceed relatively peacefully. The history of forced regime collapses in the region is quite clear: Democracy cannot be achieved by bombing or starving a nation; true democracy grows organically over time.