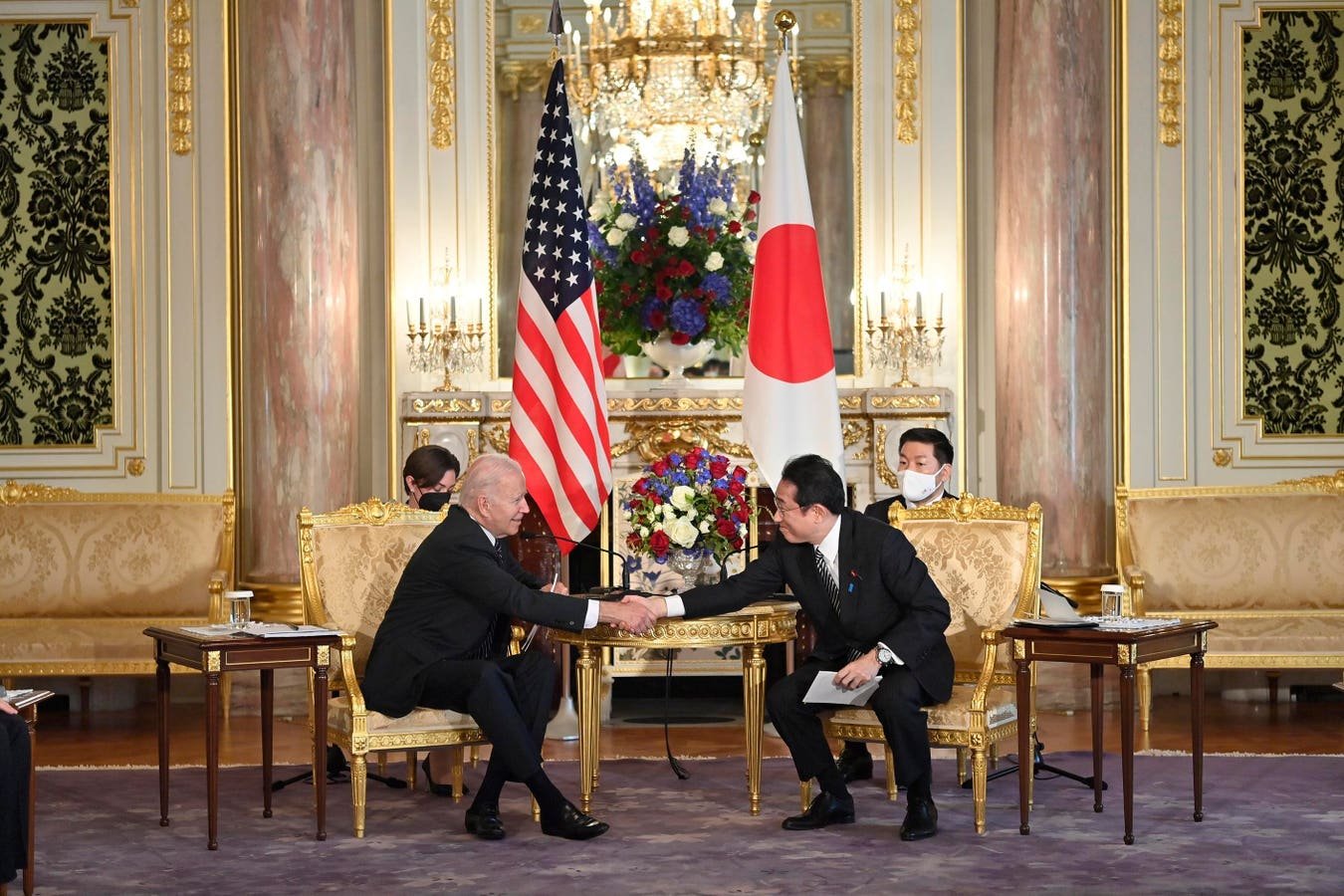

TOKYO, JAPAN – MAY 23: U.S. President Joe Biden and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida shake … [+] hands during the Japan-US summit meeting (Photo by David Mareuil – Pool/Getty Images)

On the third day of his first term in office, President Trump committed a monumental foreign policy error that undermines U.S. economic security to this day. By withdrawing the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a 12-nation agreement to strengthen trade and investment ties with countries around China’s periphery, Trump extinguished with the stroke of a pen important leverage that could have deterred Beijing’s coercive and subversive behavior of the past decade.

In the waning days of his tenure, President Biden can mitigate the consequences of Trump’s geopolitical blunder and reinforce his own administration’s “latticework” of initiatives to strengthen alliances in the Indo-Pacific by simply not blocking Nippon Steel’s acquisition of the United States Steel Corporation. But recent leaks suggesting that Biden intends to block the deal call into question the sincerity of his administration’s commitments to U.S. allies and improving the economic prospects of workers in America’s manufacturing communities – both imperatives of U.S. economic security.

Since Nippon’s original proposal one year ago, the deal has been politicized and lathered in fantastical hypotheticals about how increasing U.S. production capacity somehow threatens domestic supply chains. In early 2024, Biden expressed opposition to the deal, assuming that position would play well among Pennsylvania voters. He said: “U.S. Steel has been an iconic American steel company for more than a century, and it is vital for it to remain an American steel company that is domestically owned and operated.”

But the election is over and steelworkers and their communities in western Pennsylvania are very much in favor of seeing the deal consummated. Democratic Governor Josh Shapiro supports the deal, which will bring over $2 billion of investment into neglected production facilities, raise the pay of thousands of workers, and keep U.S. Steel’s headquarters in his state.

The naysayers include Cleveland Cliffs (a domestic competitor whose offer last year to purchase U.S. Steel was rejected by shareholders); the United Steelworkers Union (representing the interests of USW management more than those of the workers it purports to represent); K Street lawyers and lobbyists who worry the merger will impede their capacity to fill their coffers by blocking imports with trade litigation; and, of course, the politicians who pander to these protectionist interests.

President Biden hyper-politicized the issue by treating it as a question of national security. He put it before his Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) – a board comprised of nine cabinet heads and chaired by the Secretary of the Treasury that advises the president on any national security risks stemming from foreign acquisitions of U.S. companies or critical U.S. assets. The transactions that normally come to the attention of CFIUS are those with narrow sets of concerns about protecting the defense-industrial base and preventing adversaries or malicious actors from controlling critical infrastructure or accessing advanced technology with military applications.

In a letter to Nippon Steel and U.S. Steel, CFIUS expressed concerns that the acquisition could lead to a reduction of domestic steel production capacity, which would hurt needed critical transportation, construction and agriculture projects. In response, Nippon reaffirmed that it would not transfer any of U.S. Steel’s production capacity or jobs outside the United States – a concern CFIUS could mitigate by requiring Nippon to agree in writing that domestic supply would not be diminished. In any event, the gauntlet of existing U.S. tariffs on imported steel makes it highly unlikely that Nippon would even begin to consider moving production outside the tariff walls it is paying so dearly to surmount.

CFIUS also expressed concern in the letter that a Japanese company would be less supportive of domestic industry efforts to obtain tariffs on imported steel, noting: “While U.S. Steel frequently petitions for (trade remedy) relief, Nippon Steel features prominently as a foreign respondent resisting trade relief for the U.S. domestic steel industry.”[i] But Nippon affirmed that it would not interfere with any of U.S. Steel’s decisions to pursue import restrictions under the various trade remedy laws.

In any case, those concerns can hardly be considered relevant to national security.

In September, the administration announced that CFIUS would defer issuing its findings until after the election. If CFIUS sticks to its traditionally apolitical, targeted review standards and follows its statutory obligations, it will find no legitimate national security reason to recommend the president block the deal.

To the contrary, failure to consummate this transaction is the real threat to U.S. security. Japan is a major trading partner and steadfast ally of the United States in a world where U.S. commitment to the rules-based trading system and its traditional global leadership role are increasingly in doubt. Blocking the deal would reinforce perceptions – or perhaps confirm conclusions – that the United States is turning inward and leaving longtime allies in the lurch.

The capacity of the United States to continue to draw investment from abroad would diminish and discriminatory treatment of U.S. companies and investments abroad would become more common. As the world’s largest outbound foreign investor and top destination for inbound investment, and as a major importer and exporter, the United States (and its businesses) has much to lose economically. On the strategic side, an erosion of trust would frustrate US-led efforts to counter China’s predatory, mercantilist practices by discouraging Japan and other allies in Asia from diversifying critical supply chains away from China’s coercive influence.

Ever since Washington began framing its trade and technology frictions with Beijing in the context of a growing rivalry, and began using terms like “friendshoring” to make clear it distinguished between ally and possible adversary, officials from the Indo-Pacific region have been pleading with U.S. counterparts not to put them in positions where they would be forced to choose between the United States and China. But as Secretary of State Anthony Blinken said in response to this concern: “We’re not asking people to choose; we want to give [them] a choice. And that means we have to have something to put on the table.” Blocking the Nippon deal would amount to selling that table for firewood.

Forcing allies to hedge against flakey U.S. commitments to rules is the same as chasing them into more concrete trade, investment, and business deals with Beijing to “get along” and to buy assurances. That likely would further complicate U.S. access to critical minerals and other strategic inputs and embolden Beijing’s aggressive actions in South China Sea and toward Taiwan. The president will have to take all of these concerns into account.

Every day, U.S. businesses and the federal, state and local governments compete with foreign counterparts to attract high quality investment from the world’s best companies to the domestic economy. So critical is the objective that the Department of Commerce frequently sponsors trade missions and conferences where the strongest arguments for investing in the U.S. economy are touted in a grand effort to convince foreign companies to “Select USA.”

Japanese companies already account for a greater share of the stock of foreign direct investment (FDI) in the United States than any other country’s companies – with most of that investment in the U.S. manufacturing sector. Indeed, several foreign-headquartered companies (including Nippon Steel) are already heavily invested in U.S. steel production.

If a company employs U.S. workers, pays U.S. taxes, makes capital investments in U.S. factories, purchases inputs from other U.S. companies, allows it technologies and techniques to proliferate in the United States, provides outputs to other U.S. companies, economically anchors a U.S. city or region by enabling other businesses to survive and thrive, supports U.S. charities and sponsors local softball teams, it is — in all but symbolic respects — a U.S. company.

For those who may not have noticed, threats to U.S. critical infrastructure and our commercial and strategic interests are proliferating. Those threats do not come from Japan, but predominantly from China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea. The governments in those countries are intent on undermining U.S. power and influence, and the institutions and alliances that reinforce that power and influence. It would be a colossal mistake to assist our adversaries in their efforts by carelessly poisoning our own relationship with Japan.

The case for consummating the deal rests on the strategic and economic benefits it will deliver. After all, Japan is a staunch ally and has been since the signing of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty in 1960. Japan is home to over 50,000 U.S. military personnel, as well as some of the most advanced U.S. military assets. U.S. and Japanese companies work together on defense-related projects and Japan is integral to the U.S.-led efforts to deter China’s increasingly menacing behavior toward Taiwan and toward the Philippines, Vietnam and other countries in the region over various discredited maritime/territorial claims, which threatens one of the world’s most important commercial waterways.

Every bit as compelling as that affirmative case for consummation of the deal is the imperative of avoiding the strategic and economic costs of rejection. Blocking the deal on spurious national security grounds would invite many far more realistic, adverse national security and economic consequences.

***

For a deeper dive on this subject, please read: Forging Alliances: The Strategic Necessity of the Nippon-U.S. Steel Deal